Standard Of Review: 'Loving' Is A Tonic For Election Blues

This excellent film tells the story of the people behind the landmark Supreme Court civil rights decision.

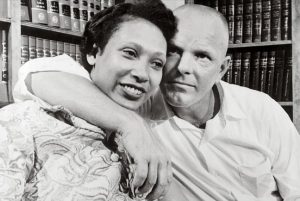

Mildred and Richard Loving in 1967

If you are like me, Tuesday ended up being one of the most shocking and disappointing days of our lifetimes, raising questions (to use the media’s favorite ominous and ambiguous phrase) about our future. Those looking to escape from reality for a few hours can take some small solace in the fact that we have finally arrived at Oscar season, and its concomitant bevy of quality films. One of those films is Loving, which opened on November 4 in limited release, and tells the story of the people behind the landmark Supreme Court decision Loving v. Virginia. Loving is an excellent film that (despite the fact that I saw it before Tuesday) serves as a much-needed tonic for what has happened this week.

Loving stars Joel Edgerton and Ruth Negga and Richard and Mildred Loving, an interracial couple living in rural Virginia. As the film opens, Mildred discovers that she is pregnant, and the couple soon travels to Washington, D.C., to wed. Not long afterward, the Lovings are both arrested for violations of Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law and plead guilty, but thanks to their attorney Frank Beazley (Bill Camp), the judge issues a suspended sentence in which the Lovings agree to leave the state for twenty-five years. Although the Lovings attempt to make a home in Washington, D.C., they soon tire of the city and are drawn back to Virginia, where their extended families live. After watching the March on Washington on television, Mildred writes to then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy about her predicament, and her case eventually finds its way to ACLU attorney Bernie Cohen (comedian Nick Kroll, whose presence almost made me laugh out loud when he first appears). Cohen and fellow attorney Phil Hirschkop, working on the Lovings’ behalf, challenge the Virginia law as unconstitutional and ultimately take the case to the Supreme Court.

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Anyone who saw Nichols’s last film, Midnight Special (which came out earlier this year), knows that he does not necessarily follow traditional rules of storytelling. In Midnight Special, Nichols throws the audience right in the middle of a story of a father breaking his superpower-wielding son out of a cult’s compound with little to no exposition. In Loving, Nichols foregoes portraying Richard and Mildred’s first meeting, or even how they fell in love. Nichols also mostly eschews explaining why Richard is so close to Mildred’s family and friends. Nichols just begins the story and forces the viewer to figure it out.

Loving also expertly portrays the human element behind a major civil rights case. The Lovings are certainly not attention-seeking; they are content to live in a house near the woods without a telephone. But as a result of their case, they are forced to sit for photographs taken by Life magazine photographer Grey Villet (Michael Shannon) and to talk to the media, despite the fact that neither Loving is particularly gregarious. Most notably, they are putting a giant target on their backs and announcing to their racist neighbors that they are in an interracial marriage.

Edgerton and Negga are both excellent in portraying the strain of living with both the lawsuit and the racist law, as well as the tension between the Lovings’ public impact and their private personas. As Richard, Edgerton is taciturn and stoic. Richard clearly loves Mildred and wants to be supportive but is extremely uncomfortable with any public attention. Negga – an actress with whom I was unfamiliar – also excels. Mildred is also quiet, but Negga gives her an air of confidence that is clearly bubbling just under the surface. Perhaps the best moments of the film are those in which Richard and Mildred act like a typical couple, such as cuddling on the couch while watching The Andy Griffith Show. These moments underscore the absurdity that by doing these mundane actions, the Lovings were breaking the law.

While there are plenty of scenes involving attorneys Cohen and Hirschkop, Loving is not their story, and they mostly show up only to explain something to the Lovings. As a result, attorneys or law students might feel frustrated that the legal aspects of the Lovings’ story are told in dribs and drabs. For example, Cohen and Hirschkop initially discuss getting the Lovings’ case into federal court, but soon afterwards the Lovings are in the Supreme Court of Virginia, without much explanation. While civil procedure aficionados might be disappointed, this choice makes sense within the context of a film told from the non-lawyer Lovings’ perspective.

Sponsored

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

My only complaint with Loving is that occasionally Nichols goes too far in playing with audience expectations. In one notable scene, Nichols cuts between Richard and his son being both in danger, as Richard is almost hit by falling debris at a worksite and his son runs after a stray baseball into the path of an oncoming car. But the whole scene is a misdirect; Richard’s son is merely scraped but not seriously hurt by the car, which nevertheless incites Mildred to insist that the family should leave Washington (amusingly, Loving is not particularly kind to Washington; on the scale of films hating on cities, it is not quite to the level of The Five-Year Engagement’s utter contempt for Ann Arbor, Michigan, but let’s just say that no one is using this film in a Washington tourism ad). In another scene, Richard is working at his house when a car forebodingly speeds into his yard, but it turns out to be Richard’s friend and a false alarm. These scenes are too cute and distract from an otherwise engaging narrative.

In light of this week’s events, I am very glad I reviewed Loving today instead of writing about something more disposable like How To Get Away With Murder. Even though the scene at the Supreme Court is extremely short, it is nice to think that there was another extremely divisive time in which progress was nevertheless made.

Harry Graff is a litigation associate at a firm, but he spends days wishing that he was writing about film, television, literature, and pop culture instead of writing briefs. If there is a law-related movie, television show, book, or any other form of media that you would like Harry Graff to discuss, he can be reached at harrygraff19@gmail.com. Be sure to follow Harry Graff on Twitter at @harrygraff19.

Sponsored

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve