Why Is The Electoral College Constitutional?

This isn't what the Framers intended.

Before you launch into, “because it’s in the Constitution, you idiot!” I already get that. My question is: Given the electoral process envisioned by the Founders and articulated in the Constitution, how exactly can we justify this Electoral College? The one we’ve been using to elect our presidents for the last century?

Before you launch into, “because it’s in the Constitution, you idiot!” I already get that. My question is: Given the electoral process envisioned by the Founders and articulated in the Constitution, how exactly can we justify this Electoral College? The one we’ve been using to elect our presidents for the last century?

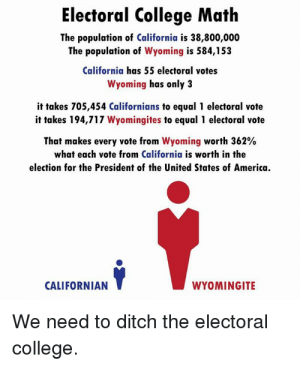

Like the rest of you, I’ve spent the last week inundated with commentary from whiners complaining about Hillary Clinton’s massive popular vote lead and railing against the Electoral College as a corrupt institution designed to give disproportionate power to a handful of folks in sparsely populated states. I’ve seen it decried as an archaic bargain to mollify slave states (which… I mean, it wasn’t the 3/5ths compromise, but I guess emotions are raw). Folks have even come up with nifty memes to highlight their perceived unfairness of a system that they never really cared about when they thought Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan were mortal locks:

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

The problem is, this disproportion isn’t the fault of the Electoral College, it’s the fault of a constitutional perversion enacted in 1921 that we’ve blindly followed ever since.

Article II of the Constitution outlines the process and it seems straightforward enough:

Each state shall appoint, in such manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a number of electors, equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or person holding an office of trust or profit under the United States, shall be appointed an elector.

Add in 3 more for the District of Columbia, and you have 538 electors. Now, obviously, the point of this provision is to protect smaller states by giving them 2 extra electors regardless of population — it’s a side effect of the Great Compromise that awarded 2 senators to every state regardless of population.

Sponsored

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Now, not to get all originalist, but the purpose of this provision of the Constitution was to ensure that the president was chosen the same way that we divvy up representation generally. But how did the Framers envision that we’d apportion representation?

The actual Enumeration shall be made within three years after the first meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent term of ten years, in such manner as they shall by law direct. The number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty thousand, but each state shall have at least one Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the state of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut five, New York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland six, Virginia ten, North Carolina five, South Carolina five, and Georgia three.

So the Constitution confers upon Congress the power to enumerate representatives by state based upon population. There are any number of ways to do this that deal with remainders and big equations, but those are boring. The point is the Framers anticipated that Congress would apportion Representatives in a manner that — generally — meant that each House member represented roughly the same number of people.

But that’s not what we do any more.

It was how the Framers intended it and how America handled its business for over 100 years. And whether or not the change made in the 1920s was the right move for the legislative branch of the country — and there’s a fair argument that a deliberative body that kept growing to over 1600 House members would be a hell of a mess — there’s really no justification for carrying that tweak over to the executive branch.

Sponsored

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

In the Reapportionment Act of 1929, Congress imposed a 435-member cap on the House of Representatives. It’s not in the Constitution, nor is it anything the Framers would have intended, but there it is. And that baggage got imported into the Electoral College because the text of Article II continues to reflect an outdated interpretation of apportionment.

The 1910 census, the census that lent itself to the 435-member House that Congress set as the standard, boasted Representatives for, roughly, every 212,430 citizens. Let’s take a look at what an Electoral College that still reflected these proportions would look like (I’m rounding up any remainder because I feel generous):

| State | Population | Electors |

| Alabama | 4,849,377 | 25 |

| Alaska | 737,732 | 6 |

| Arizona | 6,731,484 | 34 |

| Arkansas | 2,994,079 | 17 |

| California | 38,802,500 | 185 |

| Colorado | 5,355,856 | 27 |

| Connecticut | 3,596,677 | 19 |

| Delaware | 935,614 | 7 |

| District of Columbia | 672228 | 6 |

| Florida | 19,893,297 | 96 |

| Georgia | 10,097,343 | 49 |

| Hawaii | 1,419,561 | 9 |

| Idaho | 1,634,464 | 10 |

| Illinois | 12,880,580 | 63 |

| Indiana | 6,596,855 | 34 |

| Iowa | 3,107,126 | 17 |

| Kansas | 2,904,021 | 16 |

| Kentucky | 4,413,457 | 23 |

| Louisiana | 4,649,676 | 24 |

| Maine | 1,330,089 | 9 |

| Maryland | 5,976,407 | 31 |

| Massachusetts | 6,745,408 | 33 |

| Michigan | 9,909,877 | 49 |

| Minnesota | 5,457,173 | 28 |

| Mississippi | 2,984,926 | 17 |

| Missouri | 6,063,589 | 31 |

| Montana | 1,023,579 | 7 |

| Nebraska | 1,881,503 | 11 |

| Nevada | 2,839,099 | 16 |

| New Hampshire | 1,326,813 | 9 |

| New Jersey | 8,938,175 | 45 |

| New Mexico | 2,085,572 | 12 |

| New York | 19,746,227 | 95 |

| North Carolina | 9,943,964 | 49 |

| North Dakota | 739,482 | 6 |

| Ohio | 11,594,163 | 57 |

| Oklahoma | 3,878,051 | 21 |

| Oregon | 3,970,239 | 21 |

| Pennsylvania | 12,787,209 | 63 |

| Rhode Island | 1,055,173 | 7 |

| South Carolina | 4,832,482 | 25 |

| South Dakota | 853,175 | 6 |

| Tennessee | 6,549,352 | 33 |

| Texas | 26,956,958 | 129 |

| Utah | 2,942,902 | 16 |

| Vermont | 626,011 | 5 |

| Virginia | 8,326,289 | 42 |

| Washington | 7,061,530 | 36 |

| West Virginia | 1,850,326 | 11 |

| Wisconsin | 5,757,564 | 30 |

| Wyoming | 584,153 | 5 |

That looks a whole lot different, right? But that’s what the Electoral College would look like constituted the way the Framers intended. Well, maybe they’d streamline it to make it proportional with 1 “House” elector per, say, 500,000-700,000 citizens or so… the point is, these are the proportions that should govern the relative electoral power of the states if Congress hadn’t nerfed themselves radically in favor of small states by capping representation a century ago.

For what it’s worth, these numbers create a result that looks like — assuming Trump still wins about half the electoral districts in Maine — this:

Clinton: 702 Trump: 920

So, yeah, Trump would have still won despite losing the popular vote in this much more accurate reflection of the Framers’ intent. That’s just what happens when you win enough big-ticket states like Texas, Florida, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan.

But that’s what people need to get: The problem in this election wasn’t that the college gives someone in Wyoming orders of magnitude more influence over the result than someone in California, it’s that a state-based, winner-take-all system makes winning a nailbiter in one state as valuable as a blowout in another comparably larger state. Turn your guns on that problem and stop blaming the proportionality problem — which is admittedly stupid — for this result.

That’s not to say that the Electoral College — if it must stay — shouldn’t be reformed to reflect the original intent, just that such reform wouldn’t have moved the needle in this election. On the other hand (and I’m using the current numbers here rather than recalculating for 2000, but since Texas and Florida were smaller back then it, only means the margin would have been a little bigger)…

Gore: 824 Bush: 798

Well, that’s much bigger than the final electoral count in 2000.

5 to 4.