Judge Alsup Slams Patent Troll For Basically Everything

Don't try to pull a fast one on this judge.

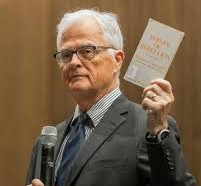

Lots of folks probably remember Judge William Alsup from the Google/Oracle mess, in which he seemed to be one of the few reasonable people in the room, who actually took the time to understand the deeper technical issues. Alsup has quite a reputation for a number of other cases as well, and one thing that seems fairly clear is that you don’t want to try to bullshit this judge who knows how to code on technical issues. You might recall in the Uber/Waymo fight, he also ordered both companies to teach him how LiDAR works and he made it clear that he wasn’t messing around:

Lots of folks probably remember Judge William Alsup from the Google/Oracle mess, in which he seemed to be one of the few reasonable people in the room, who actually took the time to understand the deeper technical issues. Alsup has quite a reputation for a number of other cases as well, and one thing that seems fairly clear is that you don’t want to try to bullshit this judge who knows how to code on technical issues. You might recall in the Uber/Waymo fight, he also ordered both companies to teach him how LiDAR works and he made it clear that he wasn’t messing around:

Please keep in mind that the judge is already familiar with basic light and optics principles involving lens, such as focal lengths, the non-linear nature of focal points as a function of distance of an object from the lens, where objects get focused to on a screen behind the lens, and the use of a lens to project as well as to focus. So, most useful would be literature on adapting LiDAR to self-driving vehicles, including various strategies for positioning light-emitting diodes behind the lens for best overall effect, as well as use of a single lens to project outgoing light as well as to focus incoming reflections (other than, of course, the patents in suit). The judge wishes to learn the prior art and public domain art bearing on the patents in suit and trade secrets in suit.

That brings us to a more recent case, involving notorious patent troll Uniloc — a company we’ve written about a bunch in the past, mainly for its buffoon like attempts at patent trolling. This includes suing over the game “Mindcraft” (the trolls were in such a rush to sue, they didn’t notice it was actually “Minecraft”), and a weak attempt to patent basic math. All the way back in 2011, we wrote about Uniloc getting smacked down by the Federal Circuit for pushing a ridiculous way of calculating patent damages.

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

It appears that in the intervening years, Uniloc hasn’t given up any of this. The company keeps buying up more patents and suing lots of companies — including Apple, which it has sued multiple times. One of those lawsuits was filed back in 2017. In response to this lawsuit, Apple argued that Uniloc didn’t actually hold the right to sue over the patent. Ridiculously, Uniloc demanded most of the details be blacked out, arguing that it was “confidential.”

It sounds like a situation not unlike the Righthaven situation from a few years ago, where the “real” holder of the patent (or, in Righthaven’s case, the copyright) retained real ownership, but created a sham transfer whereby the suing company (in this case Uniloc) really only had the right to sue, and was disconnected from the actual right to license the patent. But, it’s difficult to tell for sure, given all the black ink.

EFF got involved to protest this, and back in January Judge Alsup agreed that Uniloc couldn’t hide this info. Since then, Uniloc has been trying to convince Judge Alsup to change his mind, with a ton of filings (and a few hearings) back and forth on this issue. Earlier this week Judge Alsup more or less rejected every argument Uniloc made, even going beyond the question of redacting info.

Sponsored

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

In short, Judge Alsup says he got it right the first time, and the public’s right to know outweighs any concern Uniloc has for giving up its “secret sauce.”

This order reiterates the prior order denying plaintiffs’ initial request to seal: generalized assertions of potential competitive harm fail to outweigh the public’s right to learn of the ownership of the patents-in-suit, which patents grant said owner the right to publicly exclude others…. It also reiterates that this is particularly true where, as here, the public has an especially strong interest in learning the machinations that bear on the issue of standing in the patent context. Furthermore, the United States government bestows entities such as Uniloc the right to control the use of the purported inventions at issue. Because Uniloc’s rights flow directly from this government-conferred power to exclude, the public in turn has a strong interest in knowing the full extent of the terms and conditions involved in Uniloc’s exercise of its patent rights and in seeing the extent to which Uniloc’s exercise of the government grant affects commerce.

In other words, a patent grants you tremendous power to exclude in exchange for the public revelation of what you’ve invented. Uniloc shouldn’t be able to conduct its business in secret.

Alsup also notes that Uniloc doesn’t even come close to justifying the reasons for its requested redactions other than a general “oh, but it will hurt our business.”

… plaintiffs’ supposed risk of (still) generalized competitive harm in future negotiations from disclosure did not and does not compellingly outweigh the public’s interest in accessing this information for the reasons stated above

Sponsored

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Alsup mocks Uniloc’s reference to other patent suits (including Apple v. Samsung) in which some information was redacted by noting that that was a totally different situation involving actually confidential information from companies selling actual products, not just trolling.

Plaintiffs’ reliance on Apple Inc. v. Samsung Electronics. Co. Ltd., … is unavailing, inasmuch as the parties there sought to seal product-specific financial information (such as costs, sales, profits, and profit margins), as opposed to the licensing-specific financial information at issue here…. Plaintiffs here have no products to sell and thus their (alleged) risk of competitive harm is entirely distinguishable from that in Apple.

A few other areas where Uniloc sought to hide info, Alsup dismisses by pointing out that a “boilerplate assertion of competitive harm fails to provide a compelling reason to seal.”

And that’s not all that Alsup appears displeased with Uniloc over. Remember earlier when I talked about Uniloc running into trouble years back for using a nutty formula for trying to calculate damages? Well, Alsup notes that redacting all this info might help Uniloc hide “reasonable royalties” from being used in damage calculations, and calls out “vastly bloated figures.”

The impact of a patent on commerce is an important consideration of public interest. One consideration is the issue of marking by licensees. Another is recognition of the validity (or not) of the inventions. Another is in setting a reasonable royalty. In the latter context, patent holders tend to demand in litigation a vastly bloated figure in “reasonably royalties” compared to what they have earned in actual licenses of the same or comparable patents. There is a public need to police this litigation gimmick via more public access. We should never forget that every license has force and effect only because, in the first place, a patent constitutes a public grant of exclusive rights.

Once again, the message is: don’t try to bullshit Judge Alsup, especially on technical issues. Now, hopefully, we’ll finally see the details of Uniloc’s agreements over these patents, and why exactly Apple thinks Uniloc really has no standing to sue.

Judge Alsup Slams Patent Troll For Basically Everything

More Law-Related Stories From Techdirt:

Section 230 Keeps The Internet Open For Innovation

FBI Tells The Governor Of Florida About Election Hacking, But Says He Can’t Tell Anyone Else

Canadian Border Agents Also Routinely Demanding Passwords From Travelers And Searching Their Devices