Tax Cheats Cost U.S. At Least Four Times As Much As Welfare Fraud, And Biden Wants That Revenue

By investing about $80 billion in the IRS over the next 10 years, the Biden administration calculates that it can recover an additional $700 billion in taxes owed by the wealthy and corporations.

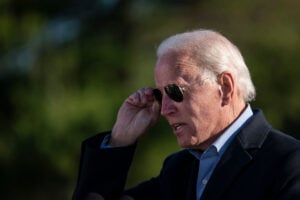

(Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Does it even matter if our government attempts to fully pay for new federal spending? Despite decades of collective hand-wringing, and countless political careers catapulted to new heights or smashed against the rocks, no one really seems to know the answer to that question.

One thing is certain though: Joe Biden’s agenda requires a great deal of spending, and his administration has put forth a significant amount of effort to at least attempt to pay for it.

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Biden has definitely floated the idea of tax increases to pay for ambitious new infrastructure initiatives and social programs, although he’s promised that there will be no tax increases for anyone earning less than $400,000 per year. Recently, however, the focus has shifted from tax increases to an often overlooked, and increasingly promising, source of revenue: actually forcing rich, sophisticated taxpayers to pay what they already owe.

Ultimately, most people pay their taxes voluntarily and on time. According to IRS estimates, 83.6 percent of American taxpayers cough up the full amount of what they owe to Uncle Sam when it comes due.

But that leaves 16.4 percent who don’t. Surprising no one, it’s not really the average W-2 wage earner who has taxes directly withheld and income automatically reported who’s skipping out on the bill at the end of the night. No, it’s mostly rich people, with their armies of tax lawyers and accountants, and, in very recent memory, bought-and-paid-for politicians.

The annual tax gap — the difference between what is collectively owed for federal tax obligations and what is actually paid — stood at about $441 billion based on an IRS analysis of data for tax years 2011, 2012, and 2013. A small amount of that money is recouped: after the application of tax enforcement efforts and when factoring in late payments, the tax gap closed to $381 billion per year.

Sponsored

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Obviously, $441 billion every year, or even the eventually reduced $381 billion tax gap, is a lot of money being left on the table. Those numbers are dwarfed though by what is expected in the coming years under current conditions. Funding for IRS enforcement efforts was slashed by the Trump administration, and audits of lower earners claiming tax credits were prioritized. Unless that IRS funding is restored, and enforcement efforts refocused, the annual tax gap isn’t going anywhere but up. The Treasury Department estimates that the tax gap had already increased to about $580 billion by 2019, and the agency projects that $7 trillion in federal taxes will go unpaid over the next decade.

In contrast, fraud and waste in assistance programs — what you still hear people referring to as “welfare” colloquially — doesn’t cost the U.S. nearly as much. In 2015, fraud, overpayments, and underpayment in all federal and state assistance programs cost the U.S. about $136.7 billion. This is not only less than a quarter of what the tax gap cost the U.S. in the latest years for which reliable figures are available, it is also artificially high in comparison, because the tax gap figures include only unpaid federal taxes whereas the welfare fraud figures also include costs to state governments.

Of course, no one wants to see costly fraud in assistance programs either, but the tax gap is really where the low-hanging fruit is in increasing revenue without even having to make dramatic changes to the current legal framework. By investing about $80 billion in the IRS over the next 10 years, the Biden administration calculates that it can recover an additional $700 billion in taxes owed by the wealthy and corporations. Biden’s idea to focus on the vast sums owed by the rich seems to be a better use of resources than what the Trump administration did: amp up audits of low-earning recipients of the earned income tax credit, and build in extra breaks for the rich.

If you want money for roads, bridges, airports, child care, and a bunch of other investments that factor in to the Biden agenda, it’s probably best to go after the money that is already owed. Both assistance program fraud and unpaid taxes are deserving of attention. But if you have two potential pools of owed money to dip into, and one is more than four times larger than the other, well, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to determine where you should focus your efforts.

Sponsored

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

Jonathan Wolf is a civil litigator and author of Your Debt-Free JD (affiliate link). He has taught legal writing, written for a wide variety of publications, and made it both his business and his pleasure to be financially and scientifically literate. Any views he expresses are probably pure gold, but are nonetheless solely his own and should not be attributed to any organization with which he is affiliated. He wouldn’t want to share the credit anyway. He can be reached at jon_wolf@hotmail.com.