Ed. note: Please welcome Dean Sonderegger to our pages. Today’s post is the first in a series called “The AI Corner: Where Technology Meets the Practice of Law.”

Ed. note: Please welcome Dean Sonderegger to our pages. Today’s post is the first in a series called “The AI Corner: Where Technology Meets the Practice of Law.”

It’s no secret that the application of artificial intelligence has the potential to transform the practice of law as well as other professions. In fact, that disruption has already begun in the accounting industry with the adoption of software solutions that help both individuals and taxpayers prepare and file their income taxes.

There are many similarities between the professions. Attorneys and accountants, after all, offer the same core value proposition as other licensed professionals: built on rigorous educational and licensing requirements controlled by the professionals themselves, accountants and attorneys have long laid exclusive claim to critical, specialized knowledge and client representations in which that knowledge is brought to bear. As such, it’s reasonable to surmise that one may be able to see the future of the legal markets by looking at the disruption that’s already occurred in the tax industry.

In analyzing disruption for both the accounting and corporate legal markets, a useful framework for thinking of enabling technology — including AI — is to think of technology as running along a spectrum of functions and impacts. At one end, the greatest impact is in providing lay people with the access and tools to perform standard tasks that previously would have required an expert. In the middle, AI is automating specialized processes, resulting in tremendous time efficiencies. And at the far end, the most advanced technologies will augment experts’ abilities to perform their “artisan” tasks, i.e. those aspects that we think of as involving analytical rigor, applying knowledge to complex fact patterns, and higher-order thinking in general.

Looking at that first spectrum as applied to the tax preparation industry, widespread adoption of expert systems centered on simple, user-friendly electronic filing of individual tax returns have enabled consumers with no accounting experience to prepare and file tax returns. Figure 1 shows this growth in adoption since 2009. In 2016, more than 53 million tax payers eFiled their individual tax returns (representing 35% of all individual returns filed) using such software, representing a huge jump in the number of people who effectively received professional tax advice without ever talking to an accountant.

Figure 1. Individual Tax Returns eFiled by Taxpayer; source: IRS.gov

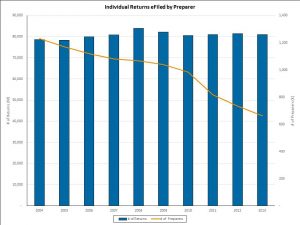

At first blush, one would think that with such penetration, the number of returns filed by professionals would have decreased. In fact, as shown in Figure 2, the number of returns filed by preparers has stayed relatively constant. What has changed is that the number of preparers themselves has decreased over time while fees have stayed relatively flat.

Figure 2. Individual Tax Returns eFiled by Preparer; source: IRS.gov

This same disruption has also hit the corporate tax market. Consider the percent of revenue generated by the top ten accounting firms which are attributable to those firms’ tax businesses. Per Accounting Today, in 2003, tax services accounted for 34% of overall revenues; in 2016, that number shrank to 25% of overall revenues. What spurred the decline? First, in-house counsel’s access to tax preparation technology dramatically increased during the time span. Second, an active regulatory environment encouraged insourcing.

However, while tax business as a percentage of revenue declined, over the same time span, overall revenue at the top ten firms grew from $24.4 billion to $53.3 billion.

Underlying this strong growth was the willingness of the accounting firms to embrace the efficiencies offered by disruptive technology; their efforts to expand and deepen specializations; and heavy emphasis on advisory services, those consulting-style services that involve an expert providing an expert-level answer to a complex problem.

According to bigfour.com, much of the accounting firms’ revenue growth can be largely attributed to growth in client advisory service offerings — areas that require more specialization and creativity, and also areas where emerging AI technologies add value in terms of additional insight — mining voluminous data for patterns, for example, when previously only a small subset of that information could be examined — not just efficiency gains borne of automation.

The world’s largest accounting firms have been increasingly active in the market for augmented intelligent solutions. Notable examples, per Economia, include KPMG’s frequent adoption of Kira, and Deloitte’s usage of IBM’s Watson. The large accounting firms have also not been shy in setting out growth strategies that depend on a continually increased capacity for specialization.

The reality is that we’re already seeing a parallel dynamic at work in the corporate law market — and it’s only getting started. Based on lessons from the accounting industry, we can predict the following about the practice of law:

First, an ongoing expansion of “expert” legal tools will disrupt the consumer legal market. Consumer tools like Legal Zoom will dramatically increase individual access to typical consumer legal needs, e.g., incorporating documents, wills, simple contracts, etc. (just as consumer tax prep software has done). This in turn will put price pressure on smaller law firms to adopt AI technologies in order to remain competitive. These firms would do well to be early adopters and demonstrate ongoing value enhancement right now — and consumer-oriented firms that resist adoption will run the risk of being rendered obsolete.

Second, “insourcing” will continue. In the larger corporate market, we’ve seen an increased spend on in-house counsel as spend on outside counsel plateaus or decreases. As was the case in the accounting industry, the continuation of the trend is expected to result both from corporate counsel’s increased access to AI technology and an in-flux regulatory environment that incentivizes bringing work in-house. Indeed, we’ve heard from multiple law firms that corporate clients have been more aggressive in pushing back on the prices for contract review as part of due diligence due to the increased availability of AI tools in document review.

Third, AI technology embedded into practitioner workflow, along with automating technology that breeds efficiency, will continue to transform the practice of law from within corporate law firms. Large corporate firms must, want to, and will invest both in expert systems that automate repeatable tasks and in augmented intelligence that will assist attorneys in their “artisanal” analytical work. This kind of machine learning offers all of the potentialities of big data mining and document analytics, natural language processing and predictive analytics.

The economic impact on the large law firms is going to be a complex determination and, to some extent, firm-dependent. Generally, expect to initially see large firms charging clients the same fees for increasingly larger bundles of service, with downward pressure on fees over time. That being said, many large law firms are looking to AI as new profit centers. The efficiencies emanating from these technologies can drive down costs, potentially expanding margins.

More importantly, many large law firms believe that the skills of their attorneys will continue to be the differentiators. AI will give lawyers the ability to provide more comprehensive counsel, but some will do better than others optimally employing AI to maximize both client value and firm profit. It’ll be those firms, and those lawyers, who grasp how to correctly insert inputs when framing data analyses, and how to interpret the outputs against the backdrop of a given client’s situation, that will sustain pricing power.

Accounting offers law firms a longer-term view that what seems to be a threat can actually be a significant opportunity — by embracing the technology, learning it, changing the service offerings mix to emphasize more specialized, analytical issues, etc., AI doesn’t mean the ultimate rise of the robot lawyer. It’s going to make some folks plenty of money, too.

May Goren Photography

Dean Sonderegger is Vice President & General Manager, Legal Markets and Innovation at Wolters Kluwer Legal & Regulatory U.S., a leading provider of information, business intelligence, regulatory and legal workflow solutions. Dean has more than two decades of experience at the cutting edge of technology across industries. He can be reached at [email protected].