In last month’s article, we discussed the fundamentals of blockchain technology, why it was created, and how it works. Here’s a quick refresher:

In last month’s article, we discussed the fundamentals of blockchain technology, why it was created, and how it works. Here’s a quick refresher:

Blockchain is a digital ledger of transactions between multiple parties. Each transaction is represented by a set (or a block) of data; the transactions themselves are linked (chained) in a way that makes it very difficult for anyone to misrepresent or hack the transaction once stored. This linking is done through the use of a cryptography algorithm known as a hash. This characteristic of blockchain is known as immutability and is one of the unique properties about blockchain technology.

The question remains as to why immutability matters — how can it positively impact the practice of law?

To examine further, let’s take a simple use case: the purchase and transfer of title to real property between two parties. This use case includes the following parameters:

- Real property is typically conveyed through the use of a deed that meets the requirements of applicable (local) law.

- Both parties to the transaction typically sign the deed as part of the closing process and that deed is then recorded at the appropriate recording office (e.g., the county clerk, etc.).

- Any liens on the title (e.g., a mortgage) are also typically recorded at the same local office.

A key part of building trust in such a transaction is making sure that i) the title is clear (any encumbrances are identified and addressed prior to or as part of the sale) and ii) the seller actually owns the property in question.

Anyone who’s been through this will tell you quickly that it’s a difficult and confusing process. In an attempt to see what the positive impact of technology could be, Cook County in Illinois commissioned a pilot program in September 2016 to investigate the use of blockchain to track and transfer property titles.

As part of that program, the following issues were identified with the existing process for recording deeds:

- Information on property is stored in many different locations and agencies in the county, many of which are paper-based or offline, making it extremely difficult for a purchaser to get a comprehensive view of any property, and

- Updates to information about property are typically verified for correct format, but not for authenticity, which leads in certain cases to real estate fraud as it’s possible to file forged documents (sometimes through the mail).

To be fair, consolidating data across multiple sources is more of a process problem than a technology problem — many database / data storage solutions are capable of addressing that — but blockchain uniquely resolves this issue in several ways:

- The immutable nature of the blockchain means that, once records are added, they cannot be modified or changed. This addresses concerns about fraudulent activity with existing records.

- Data is fully transparent. This means that anyone can get a complete view of relevant information for any property.

- Parties (individuals, businesses, or agencies) that add new records are required to digitally sign those records in a manner than validates the signing party’s identity. This eliminates another area of fraud wherein someone forges signatures on a deed of conveyance and fraudulently records a deed for property in their name.

This last point highlights another characteristic of the blockchain: identity validation. Blockchain manages identities through what is known as public key infrastructure (PKI). Under PKI, each entity (a person or an organization) is given a public and private “key.” The private key is known only to the entity and consists of a string of characters that’s used in conjunction with an encryption algorithm to add a unique digital signature to a message (or any set of data). The authenticity of the message can then be verified using that entity’s (openly shared) public key.

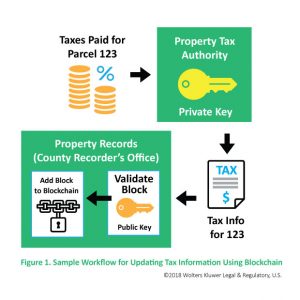

Figure 1 shows an example of how this could work for one aspect (tax information ) of real estate records. Assume that the owner pays the property tax due for a parcel of land (Parcel 123). The taxing authority then needs to update this information in the property records system so that any prospective purchasers are aware that the taxes are current and fully paid for that property.

Upon receiving payment, the taxing authority prepares a block of data, signs that data with its unique private key (known only to the taxing authority), and sends the new block to the property records system. Before adding the new block of data to the blockchain, the property records system validates the block’s digital signature with the taxing authority’s public key. The new block of data is only added if the signature can be validated. [1]

This may sound complex, but most of us actually use this very technology on a daily basis. Any time you visit a secure website — for instance, to check your bank account balance — your browser is using a public key to validate that the website is actually the site you think it is.

As part of its pilot program, the recording office at Cook County came to the conclusion that blockchain technology could indeed reduce real estate fraud and make transactions more efficient. Looking at the example above, it becomes readily apparent that such a system would require significant changes to become operational:

- A comprehensive set of existing records would have to be verified, scanned and consolidated to provide a complete view of property records.

- In order to maintain new versions of records, multiple agencies would have to develop protocols to update the ledger of records as new data (e.g., tax records) becomes available.

- Infrastructure would have to be built to securely distribute and manage a set of public/private keys for identity validation purposes.

It should be noted that while these steps would provide significant public benefit through increased transparency and fraud reduction, in all likelihood there would be minimal disruption to the role of the attorney. Attorneys would still be involved in the drafting of the deed, clearing title (although this would be made easier by such a system), and through their role as an intermediary for the transaction.

Having title records in place, however, does open up an intriguing possibility. What if there was a software program that “sits” on top of the blockchain and performs the activities of an intermediary? One could incorporate the appropriate rules (for instance, to pay off a mortgage on the property) for completing the transaction into the program and eliminate the need for an intermediary altogether. This is exactly the promise of smart contracts and the subject of next month’s article.

[1] The discerning reader will note that blockchain as implemented for Bitcoin uses the PKI technology described above to hide the identity of users. This is due to the primary application of Bitcoin being that of anonymous “digital cash” transactions… clearly an implementation to facilitate transactions of public record would have to be somewhat different (and as described herein) than that of Bitcoin to ensure appropriate transparency.

May Goren Photography

Dean Sonderegger is Vice President & General Manager, Legal Markets and Innovation at Wolters Kluwer Legal & Regulatory U.S., a leading provider of information, business intelligence, regulatory and legal workflow solutions. Dean has more than two decades of experience at the cutting edge of technology across industries. He can be reached at [email protected].