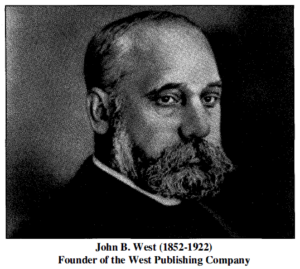

One hundred forty-five years after publishing his first regional case law reporter, 139 years after formally incorporating West Publishing Company, 124 years after launching the classification scheme that would become the key number system, and 99 years after his death, John B. West and his legacy are now revived as the topic of litigation in federal court in Delaware.

One hundred forty-five years after publishing his first regional case law reporter, 139 years after formally incorporating West Publishing Company, 124 years after launching the classification scheme that would become the key number system, and 99 years after his death, John B. West and his legacy are now revived as the topic of litigation in federal court in Delaware.

That is where the company he founded, now a business owned and subsumed by Thomson Reuters, filed suit last May against the legal research startup ROSS Intelligence, alleging that ROSS stole content from Westlaw to build its own competing legal research product.

Already, the lawsuit has forced ROSS to shut down its operations, effective yesterday. But ROSS vehemently denies the allegations and, fueled by litigation insurance, has vowed to continue the lawsuit, which it characterizes as a tactic by the acknowledged giant of legal research to quash an up-and-coming competitor.

True to that vow, ROSS initially filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, denying that it copied or used any proprietary data from Westlaw and challenging TR’s claims of copyright in case headnotes and its key number system –- a challenge that goes straight to the core of Westlaw’s business.

In December, ROSS partially withdrew that motion to dismiss and filed an answer and counterclaim in which it directly challenged TR’s copyrights in Westlaw content.

“It is well established in American law that judicial opinions and federal and state laws, including administrative rules and regulations, are not copyrightable, and must remain public as a matter of due process,” the counterclaim said.

Other aspects of Westlaw, such as its key number system and headnotes, constitute a “method of operation,” which is not eligible for protection under copyright law, ROSS argued.

Summoning West’s Spirit

Last week, in its latest litigation gambit, ROSS filed an amended answer, adding a new counterclaim in which it asserted that TR is violating federal antitrust law by maintaining monopolistic and anticompetitive control over the legal research market.

It is there, in that counterclaim, that ROSS summons the spirit of John West, to assert that it, not TR, is the true heir to his legacy of seeking to make the law more accessible to all.

The ROSS filing recounts that West and his brother established West Publishing “with laudable ambitions to provide frontier lawyers with a cheap and efficient means to learn about new cases.” But after the pair built the company into the nation’s largest legal publisher, West suddenly left the company in 1899 under cloudy circumstances.

Seeking to build a “better and fairer publishing company,” the ROSS pleading relates, West founded the Keefe-Davidson Law Book Company, but the company was never able to gain much traction.

“ROSS, not Westlaw, is trying to realize West’s laudable ambitions and make the public law truly accessible,” the counterclaim asserts in a footnote. “Westlaw instead is following the footsteps of its predecessor-in-interest, and pursuing abusive and exclusionary conduct to preserve its market power.”

Success, Then Tragedy

West’s story is even odder and more tragic than ROSS’ brief summary suggests, although many details of his life and career remain cloudy.

The ROSS summary draws from a leading source on West’s life, the 2008 article, “John B. West: Founder of the West Publishing Company,” published in the American Journal of Legal History by Robert M. Jarvis, professor of law at Nova Southeastern University’s Shepard Broad College of Law. Jarvis, in turn, drew heavily on a 1969 book, West Publishing Company: Origin, Growth, Leadership, by William W. Marvin.

The founder of modern legal research never made it past eighth grade. He fell into legal publishing by happenstance after his parents moved from Massachusetts to St. Paul, Minn., when he was 18. West found a job as a salesman for a bookstore, traveling to small towns along the Mississippi River, taking orders for office supplies and, as a sideline, legal and medical books.

Many of his customers were lawyers who often complained about the hardships of running a frontier law practice. Seeing an opportunity, West quit his job in 1872 and set himself up as a publisher and book seller focused on serving lawyers. According to Jarvis’ article, he created a line of legal forms, reprinted hard-to-find treatises, and produced an index of the Minnesota statutes.

As the business grew, in 1876, West recruited his brother Horatio to join him in the business. The two began publishing a weekly syllabus of decisions of the Supreme Court of Minnesota, which soon became the North Western Reporter, the first of West’s regional reporters and the cornerstone of the National Reporter System.

The company thrived, incorporating as West Publishing Company, and taking over a building of its own in St. Paul. Then, in 1887, West announced what Jarvis described as “an audacious plan to catalog every case” into something dubbed the American Digest Classification Scheme.

“Like the case reporter, this marked a radical leap forward, for it allowed lawyers to quickly find decisions that had considered a particular issue,” Jarvis wrote.

That, of course, grew into West’s key number system, which further fueled West’s growth, as did another decision West made — to publish all cases, not just selected decisions, so that the readers, not the publisher, could assess each one’s relative importance.

In 1893, West purchased a grand mansion in St. Paul and was perceived as a leader of the community, even being invited to Philadelphia in 1895 as part of a delegation of dignitaries to participate in the launch of the massive ocean liner, the St. Paul.

Parting Of The Ways

But West’s life turned south in 1899, when he suddenly left the company he had founded, without public explanation. No one knows, Jarvis said, whether he was pushed out or left of his accord. But within three weeks of leaving, he founded the Keefe-Davidson Law Book Company, along with two former West Publishing employees.

In his new role, West spoke publicly against his former company. In 1908, he delivered a speech at the American Association of Law Libraries annual meeting in which he called for the elimination of unofficial case reporters –- the foundation of West Publishing’s business –- in favor of prompt issuance of official reports.

He also derided the West digest system, saying it had outlived its usefulness. “Perhaps nothing has done more to prevent the permanency of digests than the false theory that cases and propositions dealing with changing conditions may be made to fit a rigid classification instead of permitting the classification to change gradually with the growth of the case law,” he said.

West’s new company struggled, exacerbated by a royalty lawsuit against it that stretched over two years and ended in a victory for the plaintiff. In 1909, West’s financial woes forced him to take his youngest son, Bronson, out of Harvard, where he was a freshman. By 1912, West was forced to shut down his company.

Tragically, the company’s failure led West’s older son, John Jr., who had joined the company after graduating from Harvard in 1906, to suffer a nervous breakdown. Admitted to a state hospital for treatment, the son hanged himself and died.

These events drove West to leave St. Paul and settle in Pasadena, Calif., where he retired. He died in 1922 of heart disease.

Meanwhile, West’s son Bronson attempted to revive the Keefe-Davidson Company. In 1915, he started a printing company in Minneapolis called The Legal Publishing Company, which he quick renamed as the Keefe-Davidson Company and relocated to St. Paul. By 1920, Bronson’s company had also closed down.

Claiming His Legacy

Jarvis, in his article about West, said it was “stunning that so pivotal a figure wallows in such obscurity.” Even so, he wrote, “every day, wherever law is practiced or taught, his remarkable innovations live on.”

Which brings us back to ROSS’ assertion that it, not Westlaw, “is trying to realize West’s laudable ambitions and make the public law truly accessible.”

From what little we know of John West, it is difficult to say whether he was an idealist or an opportunist, whether he truly wanted to democratize the law, or simply saw an opportunity to make a good living.

But there is something Jarvis says in concluding his article about West that has relevance today. How was it, Jarvis asked, that a man who did not go to college and had no training in law was able to come up with a system that revolutionized legal research and legal practice. Why had no judge or lawyer seen what he saw?

“Perhaps the answer is that they were not looking,” Jarvis concluded, “or perhaps it took an outsider to see what the cognoscenti could not.”

Those words can be applied to innovation broadly and to innovation in legal technology specifically. Often it takes an outsider to upend established businesses and established business models.

In that sense, ROSS may be right that it more closely mirrors West’s early ambitions than does the company that still bears his name.

Technology Robert Ambrogi is a Massachusetts lawyer and journalist who has been covering legal technology and the web for more than 20 years, primarily through his blog LawSites.com. Former editor-in-chief of several legal newspapers, he is a fellow of the College of Law Practice Management and an inaugural Fastcase 50 honoree. He can be reached by email at ambrogi@gmail.com, and you can follow him on Twitter (@BobAmbrogi).

Technology Robert Ambrogi is a Massachusetts lawyer and journalist who has been covering legal technology and the web for more than 20 years, primarily through his blog LawSites.com. Former editor-in-chief of several legal newspapers, he is a fellow of the College of Law Practice Management and an inaugural Fastcase 50 honoree. He can be reached by email at ambrogi@gmail.com, and you can follow him on Twitter (@BobAmbrogi).