(Image via Getty)

Given the state of race relations in this country, I guess this isn’t surprising. But I have to write about another law school professor willfully ignoring the violent history of the N-word and deciding to use it in a classroom setting pretty frequently. It’s unsettling.

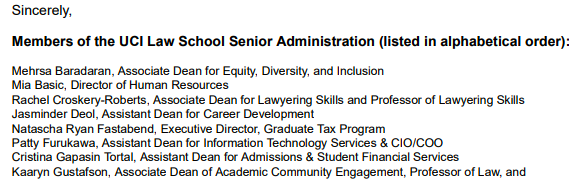

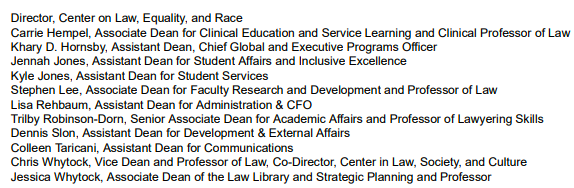

In any event, the latest incident happened at UC Irvine School of Law, where according to a statement signed by senior members of the law school administration, an unnamed faculty member used the N-word in class, and then again — multiple times — in conversations with the Dean. And that prof apparently won’t “apologize or acknowledge wrongdoing.”

7 Key Trends In Law Firm Rate Negotiations

And how to navigate them in 2026.

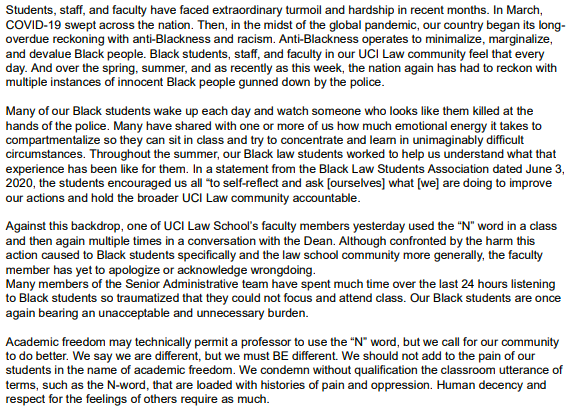

The statement strongly condemns the words of the unnamed faculty member, but suggests the banner of “academic freedom” is being flown to prevent any consequences for the professor:

[O]ne one of UCI Law School’s faculty members yesterday used the “N” word in a class and then again multiple times in a conversation with the Dean. Although confronted by the harm this action caused to Black students specifically and the law school community more generally, the faculty member has yet to apologize or acknowledge wrongdoing.

Many members of the Senior Administrative team have spent much time over the last 24 hours listening to Black students so traumatized that they could not focus and attend class. Our Black students are once again bearing an unacceptable and unnecessary burden.

Academic freedom may technically permit a professor to use the “N” word, but we call for our community to do better. We say we are different, but we must BE different. We should not add to the pain of our students in the name of academic freedom. We condemn without qualification the classroom utterance of terms, such as the N-word, that are loaded with histories of pain and oppression. Human decency and respect for the feelings of others require as much.

Let’s put aside the red herring of academic freedom, and look at the glaring thing this message leaves out: the faculty member’s name. That means there’s no public record of which professor thinks it’s just fine to throw around the N-word and prospective and future students (because this person isn’t going anywhere) do not have that valuable bit of information. That means they could unwittingly walk into the professor’s classroom — or be assigned to the professor’s class (there’s no information about whether this prof teaches mandatory 1L classes) — without being forearmed with the knowledge that the prof likes to drop the N-word.

I’m sure a lot of current students are in the know and have heard who this is, but it’s about more than just the folks at UCI right now. It is disturbing that the senior administrative team isn’t willing to name the professor. Academic freedom means a lot of things to a lot of different people, but it certainly doesn’t guarantee you anonymity for using racial slurs.

How Filevine’s New DraftAI Cuts Out Hours Of Writing Work

Now it transforms your document creation with natural language prompts.

UPDATE: Sources at the law school have reached out to Above the Law with additional information about the incident. In a follow up email the day after the original email went out, Dean L. Song Richardson sent another message to the UCI Law student body (available in full on the next page) that identified Professor Menkel-Meadow as the professor that used the N-word in class. She further informed the law school community that Professor Menkel-Meadow will not be teaching the 1L curriculum “for the foreseeable future.” Additionally, Dean Richardson said upper level students in Menkel-Meadow’s classes that have continuing concerns should reach out to the administration.

Dean Richardson also provided the following statement to Above the Law:

It is time to eliminate the use of the “N” word in legal pedagogy. In order to best educate our first-year law students, I immediately reallocated the professor’s teaching assignments to upper division courses only.

Students currently enrolled in this professor’s class may withdraw from the course for the semester if they want to do so.

I hope that all law schools will take the opportunity in this historic moment to confront structural racism in the legal academy.

UCI is committed to fostering a campus environment that is committed to equity, diversity and inclusion. This commitment is fundamental to advancing the campus’s mission as a public research university.

UPDATE 2: Professor Menkel-Meadow responded to Above the Law’s request for comment, which referenced “misrepresentations” in the account but did not specify what was misrepresented. Above the Law has sought additional clarification. Professor Menkel-Meadow provides the following context to the incident:

I assigned the attached article, [available here] where the authors (journalists) were reporting on Facebook decision making about the uses of various forms of the abhorrent “n” word (page 134), in my class on Problem Solving and Professional Judgment, with a focus on racial justice. I am a former civil rights lawyer. The article, which I have assigned before, without complaint, is about Facebook’s efforts to craft policies concerning hate speech. I did not use the word “repeatedly,” nor for any purpose other than to refer to Facebook’s issues in attempting to remove the word in the US, with difficulties that ensued, and to explain the context in which the word was used to those who did not apparently read the article or attend the class. I have written letters to my colleagues, to the Dean and to students about the context and pedagogical “mention,” not “use” of the word, which I suspect you have had access to. [Above the Law does not have access to the referenced letters, and has sought them from Professor Menkel-Meadow.]

As to the professor’s “mention” versus “use” distinction, it’s something we’ve heard before, and I have the same response. How hard is it to just not speak the word? When you say “N-word” everybody knows exactly what you mean and you avoid potentially traumatizing students listening to your words. Why is that not the obvious answer?

In her email to Above the Law, Menkel-Meadow also refers to other legal scholarship that uses the N-word. But writings from a decade+ ago that use the word hardly seem like a justification for using it out loud, in front of students, in 2020 when everyone should frankly know better.

UPDATE 3: Below is the response Professor Menkel-Meadow sent to the law school community:

Dear Law School community:

Please see below a letter I sent to our faculty this morning after the Dean sent around a communication about what was alleged to have happened in my class yesterday. Much of what is being circulated now is seriously inaccurate. So, I urge you to read the letter below and consider your current role as law students, who must learn to deal with complex and controversial issues, some of which are painful. I am the child of Holocaust survivors who suffered hate speech, dehumanizing behavior and worse (death of family members) as many in our world and country are experiencing now. As lawyers you will have to learn how to investigate facts, research law, make good arguments, interact with clients, and often deal with painful things (hate speech, discrimination, assault, rape, unjust behavior, among many other legal and social wrongs). My whole career has been devoted to doing as much as I can to educate, mediate, protest, litigate and change the world on these issues, so I fear many of you have totally misunderstood what was being discussed in my class—policies for Facebook and other platforms to regulate or do something about racist speech. The people at Facebook, including their counsel, and Stanford Law School students and faculty, who worked on these issues to create processes for taking down offensive posts and developing a court, as well as regulations, had to discuss the uses of various “n” words in order to develop their Community Standards and speech courts (see the article attached, (page 134) which has been assigned reading in several of my courses, and other’s, since it came out—there are updates for those who are interested. I have spent decades dealing with conflict on race, gender, and ethnic issues so I appreciate your expressions of pain, especially in these times, but I really don’t think I should be the focus of your anger. If I am your focal point, we are all in big trouble.

So please read the letter below, see my syllabus attached and reflect on how you are getting your information. I understand the pain many are feeling but the offensive epithet is just that– offensive, as I said in class and continue to feel it is. As you can see from the attached article, to deal with it, we must sometimes print it and yes, even occasionally speak its name, if only to denounce it and have people understand what harm it can do and then talk about what we can do about it, and other such painful expressions, or worse, the physical harm being caused to many who speak it and more, with hateful animus.

I hope all of us can take some time to reflect on this. If you are interested, there is a vast literature on the use of this and other problematic words and concepts in educational settings, especially law schools focused on justice, legal reform, arguing cases and drafting legislation.

Here is the letter sent to the faculty earlier today:

Dear Colleagues:

I have no need to hide behind any anonymity of the Dean’s letter to you all. I was the faculty member who was discussing the regulation of hate speech in the context of Facebook’s policies and recent efforts to create a Community Standards and Court to deal with problematic speech on its platform, as an exercise in “framing” a “wicked problem”. Please see the attached article (page 134) which I have assigned in class several times over several years now in discussing this problem. This class is based on a course, like mine, at Stanford Law some years ago, when the Stanford policy lab was asked to assist Facebook in dealing with hate and offensive speech. I consulted with those on the Stanford faculty who were involved in the process. The class read the article and we discussed how Facebook dealt with various forms of the “n” word in different cultures and countries (not only the US). The whole purpose of the class was to discuss the complexities of both legal and social problem solving with such issues.

For your information, I told the class, that as a child of Holocaust survivors (whose family has experienced death and harms as horrific as anything experienced here by many racial and ethnic groups) I have always deplored hate and racist speech and have valorized other countries that have regulated such offensive speech more than the US has. That is why I work in those countries (in Europe and parts of Asia) on these issues.

There are several inaccuracies and mischaracterizations in Song’s letter to our community, so I hope she will send this letter from me to the whole community. I did not “read” from the text of the article. Nor did I say the word several times, but this is bigger than factual inaccuracies.

Several decades ago I chaired the UC (and before that the UCLA) Academic Freedom committee which had to deal with many issues of things said by professors in class, some serious and offensive, and others (mostly from Law Schools) that were “hypotheticals” testing the limit of cases or legislation that some found offensive. Two of my colleagues at UCLA quoted from actual offensive language (e.g. from the Phila police department, which, as a civil rights lawyer, I often sued in the 1970s for these and worse practices), both in class and unfortunately, also on an exam, so I am quite familiar with the differences of views in what is appropriate, who takes offense, and what teachers find “instructive.” There is a fundamental difference between intentionally using a harmful and offensive epithet and referring to it with the instructional intention of rooting out such offensive terms and studying their harmful effects.

This was not the first time I have discussed these issues (as I imagine others of you who teach about speech, racial justice and similar issues have) and indeed recently I wrote about the importance of “words mattering” (see attached) which has been widely circulated in the conflict resolution community, so I am well aware of how not all people agree on how these issues should be treated. This was a class discussion about very sensitive and important issues at a public university and therefore, I think an appropriate part of my academic freedom and our students’ rights to discuss and think about these issues. But, these are different times and I do understand if some of you in our community don’t agree or have been upset about this or see it differently. In my view, the mission of our university and law school in particular is to study honestly and directly the difficult issues of our society and to shed light on productive solutions to these problems, to which I have devoted my entire career.

If anyone has any other questions I am happy to discuss.

Carrie

Read the original email below. The dean’s follow up email is on the next page.

Kathryn Rubino is a Senior Editor at Above the Law, and host of The Jabot podcast. AtL tipsters are the best, so please connect with her. Feel free to email her with any tips, questions, or comments and follow her on Twitter (@Kathryn1).

Kathryn Rubino is a Senior Editor at Above the Law, and host of The Jabot podcast. AtL tipsters are the best, so please connect with her. Feel free to email her with any tips, questions, or comments and follow her on Twitter (@Kathryn1).