The ABA To Expand Law School Diversity Data

The ABA is expanding law school diversity data but needs to go further.

Law schools will soon reveal whether students of color borrow at higher rates than their white classmates, as well as whether students of color are more likely to pay full price.

Law schools will soon reveal whether students of color borrow at higher rates than their white classmates, as well as whether students of color are more likely to pay full price.

On Friday, the Council for the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar voted to track the total number of students receiving a tuition discount at each ABA-accredited law school by race and gender. This decision builds upon the council’s decision earlier this summer to track borrowing rates by race and gender.

In practice, this will allow consumers, the public, and researchers to identify law schools where long-marginalized groups borrow or pay full price in greater numbers.

Not All Legal AI Is Created Equal

This follows nearly four years of advocacy from our organizations, Law School Transparency and the Iowa State Bar Association Young Lawyers Division. We have relentlessly implored the ABA to track and publish price and debt by race and gender, as well as to enforce its diversity standard against schools that offer higher prices to women and students of color. (Here are reports from 2018, 2019, and 2020.)

According to an important study from the Law School Survey of Student Engagement in 2016, Black and Hispanic students pay and borrow more for law school. While this study established this phenomenon at a national level, only school-specific data will cause change — whether through market, internal, or regulatory pressure.

This price inequity compounds well-known problems in law practice. Black and Hispanic lawyers, as well as women, often draw smaller paychecks for comparable work, receive fewer opportunities for promotion and leadership, and encounter other indicia of bias that limit their career trajectories and career satisfaction.

Law schools would do well to acknowledge that price inequity — and the resultant debt burdens — limit wealth-building, mobility, and happiness. They should also acknowledge that it follows from a misconceived notion of merit based on how helpful a student will be to a school’s performance on the U.S. News law school rankings.

Sponsored

How To Build And Manage Your Law Firm Rate Sheet

Trust The Process: How To Build And Manage Workflows In Law Firms

A Law Firm Checklist For Successful Transaction Management

A Law Firm Checklist For Successful Transaction Management

However, these new data requirements only go partly toward addressing the underlying problem. At this time, the ABA has only committed to tracking whether students borrow or receive a tuition discount — not how much they borrow or pay by race, gender, or otherwise.

Without further refinement, a $500 discount on $50,000 annual tuition would count the same as a full scholarship. That white students borrow $28,000 less than Black students (according to an ABA Young Lawyers Division survey) would be completely lost in the mix. These basic disclosures might have some positive impact — but it’s unlikely to reveal much, provide sufficient support for enforcement of the diversity standard, or spur major change.

But the good news is that, according to the Section of Legal Education’s managing director, Bill Adams, the committee in charge of these recommendations plans to further discuss what questions to ask and what to report that would be both “understandable and helpful.”

The recipe for change starts with significantly greater transparency. We have proposed frequency distribution as the ideal mechanism. The underlying data would be helpful to the ABA and researchers. Smart presentation would provide helpful, understandable information for pre-law students and the public.

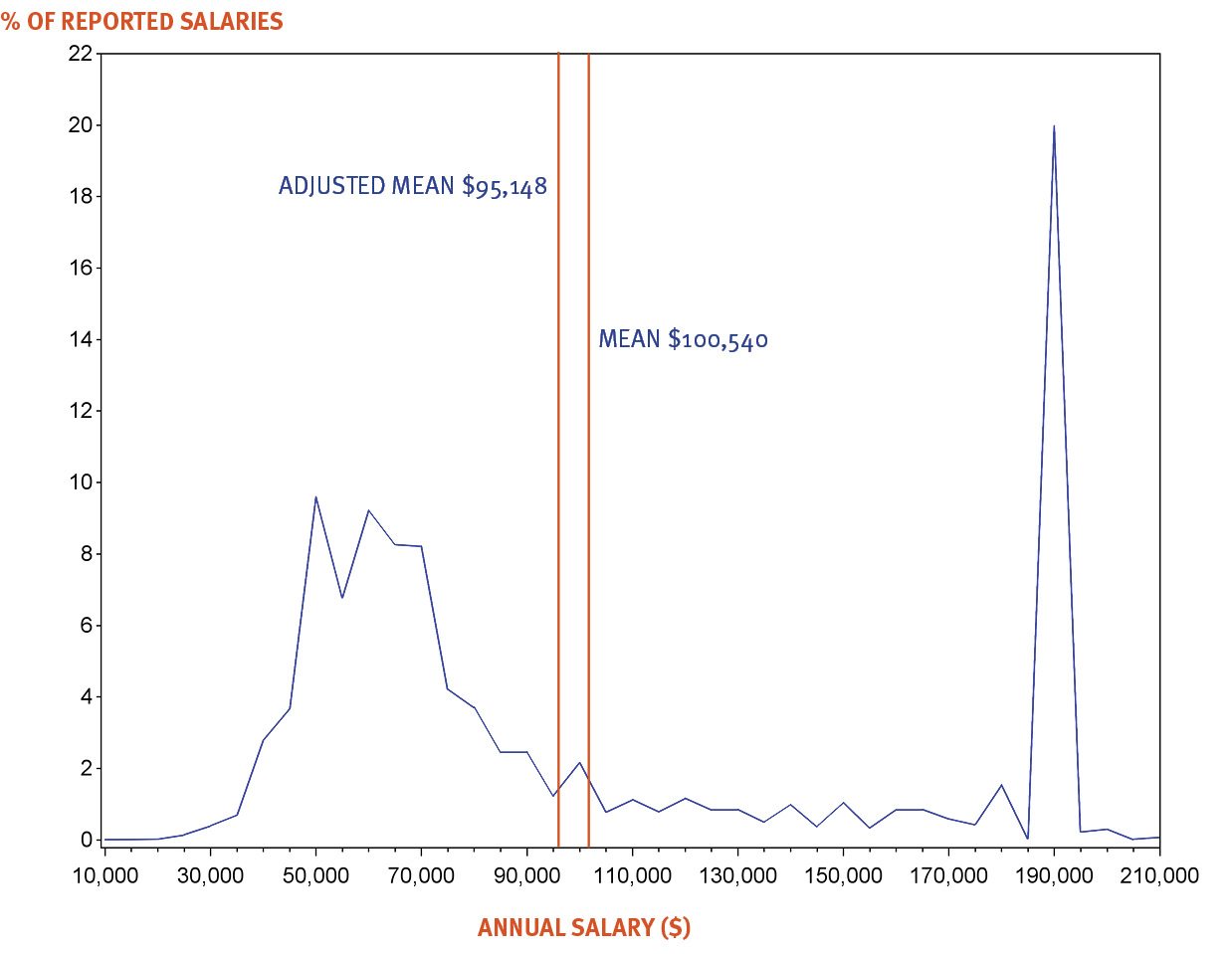

Under our proposal, schools would publish the distribution of tuition discounts and student borrowing by race, gender, and overall. In legal education, the most famous application of a frequency distribution is NALP’s bimodal salary distribution curve:

Sponsored

How Savvy Lawyers Build Their Law Firm Rate Sheet

Not All Legal AI Is Created Equal

This curve continues to shape how policymakers, researchers, consumers, and the public understand entry-level salaries. In 2019, the mean salary for reporting graduates was $100,540. However, very few graduates made at or near that amount. Instead graduates starkly fell into one of two categories — around $190,000 on the one side and between $50,000 and $70,000 on the other. This method of data presentation is impactful because readers must confront the reality of individuals that make up the averages, not just the averages themselves.

As applied to tuition prices and debt, a frequency distribution would remind stakeholders that individual students fall into a wide range. This can expose blind spots and signal opportunities for change. We believe the resultant data would allow legal educators and policymakers to confront difficult realities and to direct resources in a manner that strengthens and stabilizes the law school pipeline, rather than undermines it.

The ABA is on the right track, but the next step remains necessary and urgent.

Kyle McEntee is the executive director of Law School Transparency, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit with a mission to make entry to the legal profession more transparent, affordable, and fair. You can follow him on Twitter @kpmcentee and @LSTupdates.

Kristen Shaffer is the president of the Iowa State Bar Association Young Lawyers Division. She is a partner and vice president at Shuttleworth & Ingersoll in Coralville, IA, where she focuses on family law and litigation.