Why 2022 Is Already A Term Like No Other

The Court has yet to release a single slip opinion thus far in the 2022 Term.

This is a historic year for the Supreme Court. After a second term with a conservative supermajority, the Court is once again positioned to make key decisions along ideological lines. While the Roberts Court will be remembered for its ideological splits and key decisions in the areas of individual rights and liberties, it will also be remembered for its slow decision making process and curtailed number of decisions each term. This term follows the same trajectory.

This is a historic year for the Supreme Court. After a second term with a conservative supermajority, the Court is once again positioned to make key decisions along ideological lines. While the Roberts Court will be remembered for its ideological splits and key decisions in the areas of individual rights and liberties, it will also be remembered for its slow decision making process and curtailed number of decisions each term. This term follows the same trajectory.

This story could be about the 52 cases slated for argument so far this term and the possibility that the Court will once again undercut its lowest production ever in terms of argued cases. Instead, it is about the lack of decisions so far this term. The Court has yet to release a single slip opinion thus far in the 2022 Term. This in and of itself is a record for the slowest release time in the Court’s history. When we look at opinions in argued decisions and the lack of any decided cases, the distinction between this term and all others is incredibly stark as is evident below.

The graph above tracks the number of days between the first oral argument in a term and the first decision in an argued case since 1870 (decisions prior to 1870 were reached even quicker). The earliest that we will see a decision in an argued case this term is on January 3, 2023. That date marks 92 days since the first argument this term on October 3, 2022. The most time the Court has taken for its first decision in past terms was 65 days and so this marks minimally a 40% increase in time for this term.

What are the mechanisms at work here? One might point to the friction on the current Court as a possible rationale. Last term, however, the Court’s first opinion in an argued case was released in fewer than 50 days after the first argument and the Court’s composition was ideologically the same (swapping in Jackson for Breyer). This then may be an unsatisfying explanation for the Court’s slow productivity this term.

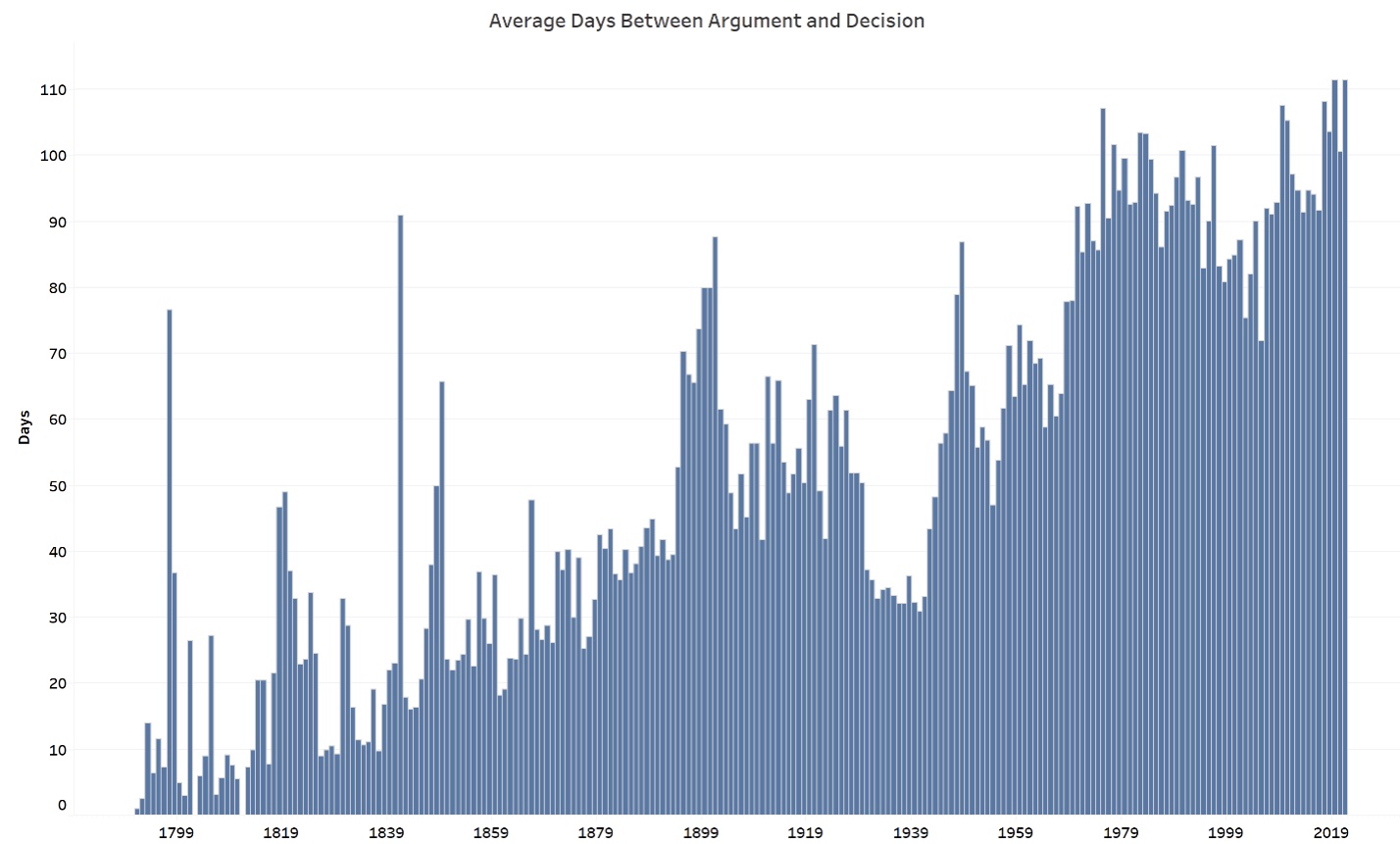

Other indicators do not shed much light on the difference between this term and all others either, although they do show how differences in the current Court may have set the stage for this kind of production. When we look at the average time between arguments and decisions across terms, we see the steady rise in time.

Several of the blips in previous terms are because of arguments that were not resolved in previous terms and when you remove such outliers the incline to the current times to decisions are more pronounced.

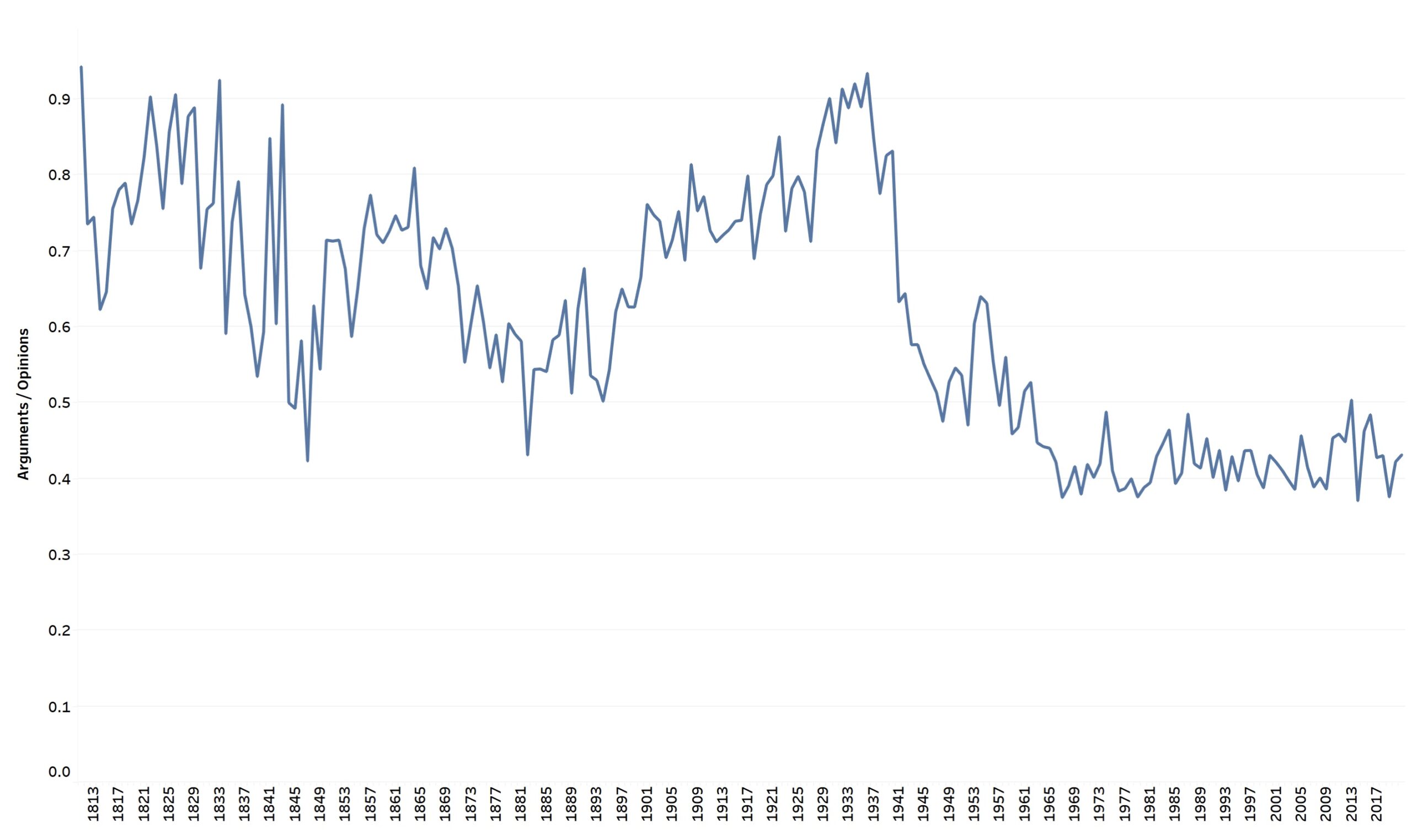

From this we might expect a steady rise in the time it takes the Court to make decisions but not a huge jump in any one year. Another explanation may be that the justices write so many separate opinions each term, which slows down the time it takes to release decisions. This explanation appears unsatisfying as well. If we look at the total number of arguments divided by the total number of majority and separate opinions each term, we see a drop in this ratio over time but not a huge plunge.

This in and of itself is not a great predictor of aberrations in the pace of decision releases. One might also aggregate the data on the number of pages per opinion to track if longer pages per decision each term slows down the Court’s production. This still would not explain the difference between this term and all terms prior to this one. Add to this the fact that we are likely to see several unanimous decisions when the first opinions are finally released this term as we have seen in the past and the bevy of pages the Court releases overall in a term would not help explain why the Court has been so slow to release a single decision this term.

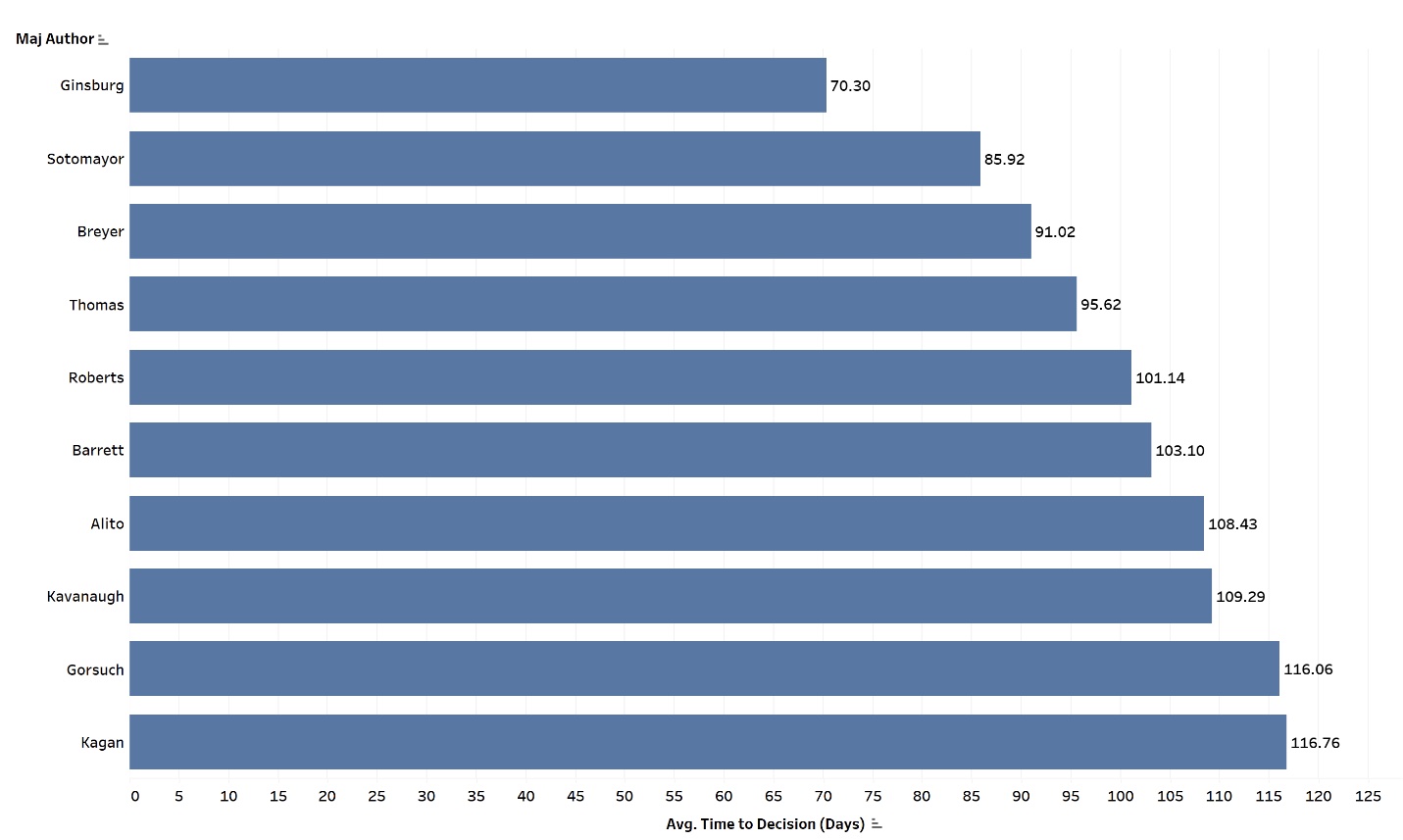

What can we expect? One thing that the past should shed light on is who we should expect to write the first decisions this term. The graph below shows the fastest authoring justices on this or recent Courts.

Justice Sotomayor is the most obvious choice of a justice to author the first decision this term. If the first decision has few if any dissents as can be expected, then it is likely to be delegated to one of the liberal justices as they will most likely author decisions with the fewest dissents this term. Since we do not have any data to base suppositions on Justice Jackson’s authoring pace and Justice Kagan tends to take more time with her authorship, Justice Sotomayor is an obvious choice for the author of the Court’s first decision.

We will not likely ever have a concrete answer for why the Court has been so slow in releasing opinions this term, but this is not surprising given the Court’s opaque nature in general. Since the Court has already significantly cut down its total decision output each term though, this is another crystal clear sign of the decreased productivity of the modern Court.

* The US Supreme Court Database was used to locate decision dates for this post.

Read more at Empirical SCOTUS….

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. For more information write Adam at [email protected]. Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.