What is the Supreme Court’s most important work? Although people’s answers may vary, one of the Court’s most important outputs is its opinion language.

What is the Supreme Court’s most important work? Although people’s answers may vary, one of the Court’s most important outputs is its opinion language.

Through its precedent, the Court develops standards for people to follow and for lower courts to articulate in subsequent decisions. Precedent guides decision making from the top down and affects outcomes for millions of individuals.

What cases are likely to drive this jurisprudence in the near future? The Court’s medium and short-term citation history provides some insight (the data were procured from Westlaw citation count searches).

Over time, the most cited cases have dealt with standards for motions to dismiss and motions for summary judgment. These cases establish the necessary elements to bring a case as a threshold matter and so they are articulated by lower courts time and again. The most cited cases over time clarified these standards. The older decisions, Anderson v. Liberty Lobby (≈ 325,000 case cites) and Celotex v. Catrett (≈ 303,000 case cites) and the newer ones Twombly (≈ 313,000 case cites) and Iqbal (≈ 289,000 case cites) far outpaced all other decisions based on citation count.

Twombly and Iqbal continue to provide the criteria necessary to pass summary judgment / motion to dismiss stage of litigation and so there has not been any cases as consequential in this area since the Iqbal decision in 2009. So where else has the Roberts Court’s jurisprudence pushed the pendulum?

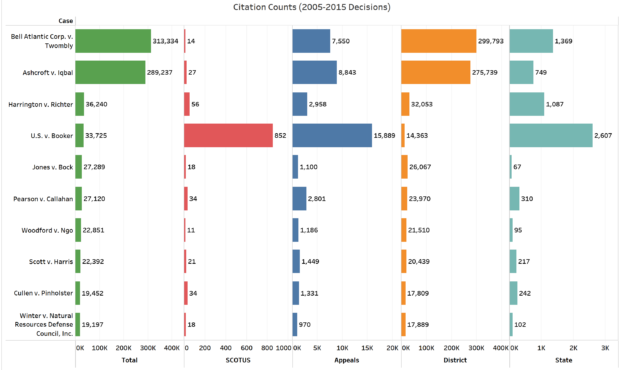

2005 to 2015

Cases tend to fall into two main areas: trial standards and criminal procedure. These types of decisions are clearly the most dominant for cases decided between 2005 and 2015 as shown below (click to enlarge).

After Twombly and Iqbal the next three cases relate to criminal procedure. Harrington v. Richter (2011) helped to set the federal court, state court deference standard in habeas corpus matters, United States v. Booker (2005) set the precedent that the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines were advisory rather than mandatory, and Jones v. Bock (2007) set the standard for exhaustion of remedies prior to a civil rights action under the PLRA.

Examples of the Court’s use of these decisions helps to convey the impact. Justice Sotomayor relied on Twombly in Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. v. Siracusano writing,

“We believe that these allegations suffice to “raise a reasonable expectation that discovery will reveal evidence” satisfying the materiality requirement, Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 556, 127 S.Ct. 1955, 167 L.Ed.2d 929 (2007), and to “allo[w] the court to draw the reasonable inference that the defendant is liable for the misconduct alleged,” Iqbal, 556 U.S., at 678, 129 S.Ct., at 1949.. The information provided to Matrixx by medical experts revealed a plausible causal relationship between Zicam Cold Remedy and anosmia.”

In Hughes v. United States, Justice Kennedy cited United States v. Booker in the following passage:

“After this Court’s decision in United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220, 125 S.Ct. 738, 160 L.Ed.2d 621 (2005), the Guidelines are advisory only. But a district court still “must consult those Guidelines and take them into account when sentencing.” Id., at 264, 125 S.Ct. 738; see also 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a)(4). Courts must also consider various other sentencing factors listed in § 3553(a), including “the need to avoid unwarranted sentence disparities among defendants with similar records who have been found guilty of similar conduct.” § 3553(a)(6).”

Looking at opinion authorship, Justices Souter and Kennedy authored the majority opinions in Twombly and Iqbal respectively. Stevens authored the majority opinion in Booker, Alito in Pearson and Woodford, Kennedy as well in Harrington, Scalia in Scott, Roberts in Winter and Jones, and Thomas in Cullen.

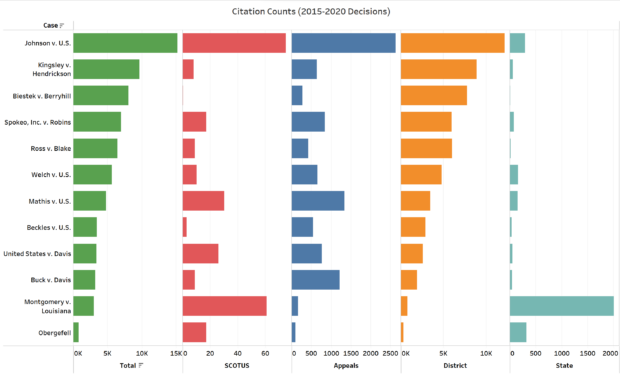

2015 to 2020

Sentencing and related criminal decision areas take the top ranks for the period of 2015-2020 but alongside these decisions we have several that deal with standards at the case level (click to enlarge).

The top cited case, Johnson v. United States (2015) affected thousands of sentences holding the Residual Clause of the Armed Career Criminal Act was unconstitutionally vague and Kingsley v. Hendrickson (2015) sets the standard for pretrial detainee excessive force claims. In terms of trial standards, Spokeo v. Robins (2016) clarified Article III’s standing and injury requirements while Biestek v. Berryhill (2019) looked to the underlying data an expert needs to proffer to support his or her testimony.

The reach of Johnson v. United States was clarified in several subsequent Supreme Court decisions including in Beckles v. United States where Justice Thomas wrote,

“In Johnson, we applied the vagueness rule to a statute fixing permissible sentences. The ACCA’s residual clause, where applicable, required sentencing courts to increase a defendant’s prison term from a statutory maximum of 10 years to a minimum of 15 years. That requirement thus fixed—in an impermissibly vague way—a higher range of sentences for certain defendants. See Alleyne v. United States, 570 U.S. 99, 112, 133 S.Ct. 2151, 2160–2161, 186 L.Ed.2d 314 (2013) (describing the legally prescribed range of available sentences as the penalty fixed to a crime).

Unlike the ACCA, however, the advisory Guidelines do not fix the permissible range of sentences. To the contrary, they merely guide the exercise of a court’s discretion in choosing an appropriate sentence within the statutory range. Accordingly, the Guidelines are not subject to a vagueness challenge under the Due Process Clause. The residual clause in § 4B1.2(a)(2) therefore is not void for vagueness.”

Justice Thomas also brought up Article III requirements from Spokeo in dissent in June Medical v. Russo when he wrote,

“…most recently, in Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins, 578 U. S. ––––, 136 S.Ct. 1540, 194 L.Ed.2d 635 (2016), the Court appeared to incorporate the rule against third-party standing into its understanding of Article III’s injury-in-fact requirement. There, the Court stated that to establish an injury-in-fact a plaintiff must “show that he or she suffered ‘an invasion of a legally protected interest’ that is ‘concrete and particularized’ and ‘actual or imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical.’ ” Id., at ––––, 136 S.Ct., at (slip op., at 7) (quoting Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560, 112 S.Ct. 2130, 119 L.Ed.2d 351 (1992)). The Court further explained that whether a plaintiff “alleges that [the defendant] violated his statutory rights” rather than “the statutory rights of other people ” was a question of “particularization” for an Article III injury. 578 U. S., at ––––, 136 S.Ct., at (slip op., at 8) (internal quotation marks omitted). It is hard to reconcile this language in Spokeo with the plurality’s assertion that third-party standing is permitted under Article III.”

Obergefell was included in this set not because of its high citation count but rather to show how a decision that is so often discussed in the media is not generally cited as frequently as other, lesser known cases that are more generally applicable across case types.

Looking at majority opinions by author, Kennedy has three from this set with Welch, Obergefell, and Montgomery v. Alabama (a state level death penalty decision). Kagan also has three decisions with Mathis, Ross, and Biestek. Other justices have one including Alito in Spokeo, Breyer in Kingsley, Scalia in Johnson, Thomas in Beckles, Gorsuch in United States v. Davis, and Roberts in Buck v. Davis.

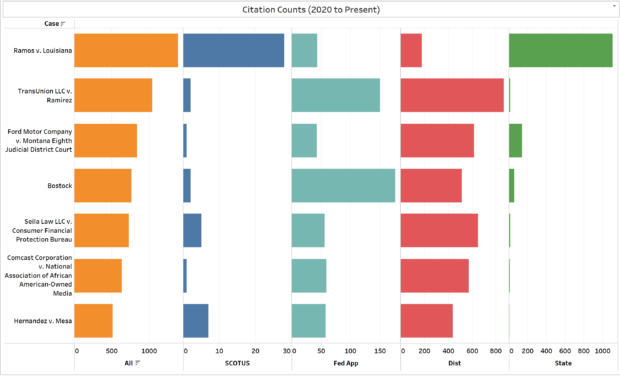

2020 to Present

We have likely not seen any cases decided since 2020 that will reach the citation ranks of Twombly, Iqbal, Johnson, or several other highly cited cases from either of the two previous Roberts Court Eras. The top cited decisions since 2020 deal with criminal and civil rights issues along with jurisdiction related concerns (click to enlarge).

In Ramos v. Louisiana, the Court incorporated the Sixth Amendment requirement of a unanimous verdict for criminal defendants to the states. Justice Thomas cited Ramos in his concurrence in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue,

“I argued in dissent that this original motivation, though deplorable, had no bearing on the laws’ constitutionality because such laws can be adopted for non-discriminatory reasons, and “both States readopted their rules under different circumstances in later years.” Id., at ––––, 140 S.Ct. at 1426. But I lost, and Ramos is now precedent. If the original motivation for the laws mattered there, it certainly matters here.”

The next most cited case, TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, looks at class action Article III standing requirements. Chief Justice Roberts cited Ramirez in FEC v. Cruz stating,

“the Government says, the Committee has not yet reached the cap in Section 304 on the use of post-election funds, and can still repay the remaining balance without running afoul of that statutory restriction. It is instead the agency’s regulation—with its 20-day limit—that prevents repayment of the final $10,000. This matters, the Government insists, because “[s]tanding is not dispensed in gross,” and plaintiffs must establish standing separately for each claim that they press and each form of relief that they seek. Brief for Appellant 17 (quoting TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, 594 U. S. ––––, ––––, 141 S.Ct. 2190, 2208, 210 L.Ed.2d 568 (2021)). A challenge to the regulation, the Government argues, is separate from a challenge to the statute that authorized it…

Even under the Government’s account, appellees have standing to challenge the threatened enforcement of Section 304. The present inability of the Committee to repay and Cruz to recover the final $10,000 Cruz loaned his campaign is, even if brought about by the agency’s threatened enforcement of its regulation, traceable to the operation of Section 304 itself. An agency, after all, “literally has no power to act”—including under its regulations—unless and until Congress authorizes it to do so by statute.”

While on the high end for citations for the 2020 to present period, Bostock v. Clayton County is an anomaly in terms of the cases explored in this post as it, like Obergefell, deals more with a civil liberty than with a trial court standard.

Justice Kagan cited Bostock in dissent in West Virginia v. EPA,

“The majority says it “cannot ignore” that Congress in recent years has “considered and rejected” cap-and-trade schemes. Ante, at –––– – ––––. But under normal principles of statutory construction, the majority should ignore that fact (just as I should ignore that Congress failed to enact bills barring EPA from implementing the Clean Power Plan). As we have explained time and again, failed legislation “offers a particularly dangerous basis on which to rest an interpretation of an existing law a different and earlier Congress” adopted. Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 U. S. ––––, ––––, 140 S.Ct. 1731, 1747, 207 L.Ed.2d 218 (2020).”

Kagan also cited Bostock in dissent in Brnovich v. DNC,

“Such a law will typically come to encompass applications—even “important” ones—that were not “foreseen at the time of enactment.” Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 U.S. ––––, ––––, 140 S.Ct. 1731, 1750, 207 L.Ed.2d 218 (2020). To prevent that from happening—as the majority does today, on the ground that Congress simply must have “intended” it—is “to displace the plain meaning of the law in favor of something lying behind it.” Ibid.; see id., at ––––, 140 S.Ct. 1731, 1753 (When a law is “written in starkly broad terms,” it is “virtually guaranteed that unexpected applications [will] emerge over time”).”

Bostock has also played an important role in several lower court decisions including in Judge Lagoa’s 11th Circuit concurrence in Adams by and through Kasper v. School Board of St. Johns County,

“And a definition of “sex” beyond “biological sex” would not only cut against the vast weight of drafting-era dictionary definitions and the Spending Clause’s clear-statement rule but would also force female student athletes “to compete against students who have a very significant biological advantage, including students who have the size and strength of a male but identify as female.” Id. at 1779–80. Such a proposition—i.e., commingling both biological sexes in the realm of female athletics—would “threaten[ ] to undermine one of [Title IX’s] major achievements, giving young women an equal opportunity to participate in sports.” Id. at 1779.”

Looking at the majority authors of the Supreme Court opinions since 2020, Justice Gorsuch wrote in Bostock and Comcast, Justice Kagan in Ford Motor, Alito in Hernandez, Roberts in Seila Law, and Kavanaugh in TransUnion.

These citation counts provide insight into which decisions will most likely have the most lasting jurisprudential impact on the courts. They show that the general population’s expectations of the most important cases do not necessarily translate to the cases that have the biggest impact on case law. This also provides some insight into what we can expect from the cases argued this term and that even the most notable decisions will likely not have the greatest impact on citations. Lastly, we have some sense of where these cases will play the biggest roles. Most but not all will play the greatest role in the district courts. Some, like Johnson will have downstream effects on other impactful cases that will consequently affect the initial case’s citations as well. Although we have only one decision on the merits so far in the 2022 term, we can expect some unexpected and lesser discussed cases from this term to also be the most cited in the future.

Read more at Empirical SCOTUS….

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. For more information write Adam at [email protected]. Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.