Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett, once celebrated as a stalwart conservative and a crowning achievement of the Trump presidency, now finds herself under fire from the very base that championed her confirmation. Her recent vote in Department of State v. AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, where she sided with Chief Justice John Roberts and the Court’s liberal bloc to reject former President Donald Trump’s attempt to freeze nearly $2 billion in foreign aid, has ignited a firestorm of criticism from the MAGA movement and right-wing commentators. Accusations of her being a “DEI judge” and a “rattled law professor” have flooded social media, with figures like Mike Davis and Laura Loomer leading the charge.

For many conservatives, Barrett’s occasional alignment with the Court’s liberal wing—seen in cases involving executive power, procedural fairness, and environmental regulation—has been a bitter disappointment. As NBC News reported, MAGA activists have turned against Barrett, with Davis calling her “weak and timid” and accusing her of having “her head up her a–.” Similarly, The Guardian highlighted how right-wing figures like Mike Cernovich and Mark Levin have labeled her a “DEI hire” and “evil,” suggesting her appointment was more about identity politics than conservative judicial philosophy.

4 Ways Your Firm Can Build Economic Resilience

It’s the key to long-term success in an uncertain business climate.

Despite this backlash, some conservatives have come to Barrett’s defense. CNN noted that prominent legal figures like Leonard Leo of the Federalist Society have argued that the criticism is an overreaction to a procedural ruling, not a substantive one. Hiram Sasser of the First Liberty Institute pointed out that Barrett’s vote in the USAid case was preliminary and did not indicate her final stance on the merits. Meanwhile, Public Discourse pushed back against the narrative, reminding critics that Barrett has been a reliable conservative vote in landmark cases like Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade.

Barrett’s defenders argue that her occasional breaks from the conservative bloc reflect a commitment to judicial restraint and legal principles rather than political loyalty. As Newsweek observed, Barrett and Roberts have previously joined the liberal justices to check executive overreach, as seen in their decision to deny Trump’s request to delay sentencing in his New York hush-money case. These rulings, while unpopular with some on the right, underscore Barrett’s independence.

As the Supreme Court continues to navigate high-stakes cases, Barrett’s judicial philosophy—rooted in legalism rather than partisanship—has made her both a target for criticism and a beacon of hope for those seeking moderation in an increasingly polarized Court. Whether she is a “disappointment” or a principled jurist depends on whom you ask, but one thing is clear: Amy Coney Barrett is no longer the unifying conservative figure many had hoped for.

Is there any credulity in the analysis of Barrett pulling apart from her conservative colleagues on the Court? Let’s unpack the data.

Ready for What’s Next: 5 Ways to Strengthen Economic Resilience

Get five practical tips to spot cash flow red flags early, speed up payments, track spending in real time, and build stronger client trust through clear, transparent billing—download the ebook.

Statistics

Agreement

The first way to analyze Justice Barrett’s voting proclivities is by looking at who she aligns with most frequently on the Court based on the Court’s opinions. So far this term Barrett has not voted on the same side as the justices the following number of times: Thomas (2), Gorsuch (3), Kagan (2), Sotomayor (3), Jackson (4), Kavanaugh (3), and Roberts (3), Alito (1). The graph below shows the percentages of shared votes with Justice Barrett and each other justice on the Court for the 2020 through 2023 Supreme Court terms.

Barrett’s voting agreement patterns from 2020 to 2023 reflect her alignment with the Supreme Court’s conservative wing while showing some variation in agreement with liberal justices. Throughout her tenure, she consistently exhibited high agreement with Justices Kavanaugh and Gorsuch, often exceeding 90%, as well as strong alignment with Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito. Her agreement with Justice Thomas remained high but showed slight declines in recent terms.

Among the Court’s liberal justices, Barrett’s agreement percentages were notably lower, especially in 2021, when she agreed with Justices Breyer (56%), Kagan (57%), and Sotomayor (48%) at the lowest levels of her tenure. However, by 2022 and 2023, her agreement with liberal justices, particularly Sotomayor and Kagan, increased into the mid-to-high 60s, reflecting instances of cross-ideological alignment. Her agreement with Justice Jackson, who joined the Court in 2022, hovered around 68-75%.

Overall, Barrett has remained firmly aligned with the conservative bloc while demonstrating a capacity for agreement across ideological lines in certain cases, particularly in the most recent term.

Differences

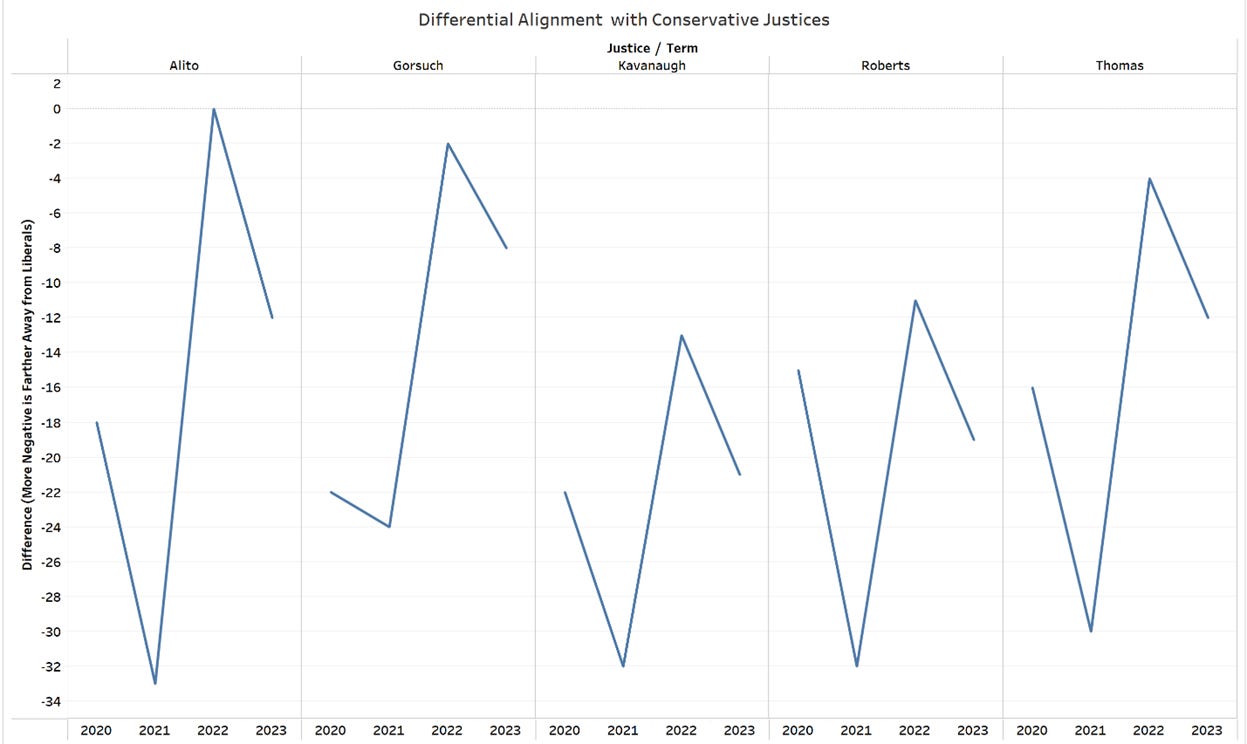

The next statistics highlight Justice Barrett’s ideological alignment with her conservative colleagues relative to her agreement with Justice Kagan, the liberal justice she most frequently aligned with each term. A more negative value indicates a greater distance from Kagan and closer agreement with a conservative justice, while values approaching zero suggest a more balanced alignment between the two.

In the 2020 and 2021 Terms, Barrett’s voting pattern placed her firmly in the conservative bloc. The differences were notably large, particularly in 2021, when her agreement with Justices Alito (-33), Roberts (-32), and Kavanaugh (-32) showed a strong conservative lean. This suggests that in her early tenure, she was ideologically closer to her conservative colleagues than to Kagan by a significant margin.

However, in the 2022 Term, Barrett’s alignment appeared to shift slightly. While she remained closer to conservatives overall, the differences between her agreement with Kagan and the conservative justices narrowed. Notably, her difference with Alito reached zero, indicating equal agreement with both him and Kagan. Similarly, her alignment with Gorsuch (-2) and Thomas (-4) showed a more moderate stance compared to the previous terms.

By the 2023 Term, Barrett’s ideological position remained conservative but showed further moderation. The differences with Thomas and Alito (-12 each) and Gorsuch (-8) were smaller compared to earlier years. However, her gap with Kavanaugh (-21) remained more substantial, suggesting that while she continued to vote with conservatives, her alignment was not uniform across all cases.

These trends suggest that while Barrett consistently leans conservative, her level of agreement with her colleagues fluctuates over time, and in certain cases, she appears to take a more moderate stance.

Close Cases

A lot of the commentary on Barrett has to do with her function as a swing vote. In reality this happens relatively infrequently. To see how Barrett aligns with the liberal justices in close cases I tracked the number of times Barrett has voted on the same side as at least two of the liberal justices in 5-4 decisions since she joined the Court. It happened once so far this term in City and County of San Francisco v. EPA where Barrett dissented along with Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson. In another environmental case, Ohio v. EPA from OT 2023, the justices’ voting alignment was the same.

This happened in five other cases making six of the 30 total 5-4 decisions between OT 2020 and OT 2023 or 20% of the time. The other cases were Bittner v. US, National Pork Producers v. Ross, Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo v. Texas, Becerra v. Empire Health, and Goldman Sachs v. Arkansas Teachers’ Retirement System making for one case in 2020, two in 2021, two in 2022, and one in 2023 showing no great increase over her time on the Court.

These cases share common themes, in resolving disputes over regulatory and administrative law, economic regulation, state-federal authority conflicts, and taxation.

In Becerra v. Empire Health Foundation (2021) and Ohio v. EPA (2023), the Court interpreted federal regulations, such as Medicare reimbursement and environmental rules. Cases like Goldman Sachs Group Inc. v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System (2020) and National Pork Producers Council v. Ross (2022) focused on economic regulations, examining securities fraud and state agricultural laws’ impact on interstate commerce. Conflicts between state and federal authority arose in Ysleta del Sur Pueblo v. Texas (2021) and Ohio v. EPA (2023), while Bittner v. United States (2022) addressed financial penalties for failing to report foreign bank accounts. Together, these cases deal with balancing government authority, economic activity, and individual rights.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s tenure on the Supreme Court has been a fascinating study in the interplay between unwavering conservative principles and a pragmatic, case-by-case approach that occasionally aligns her with more moderate or even liberal perspectives. Rooted in textualism, originalism, and judicial restraint, Barrett’s jurisprudence reflects a deep commitment to the rule of law. Yet, her willingness to prioritize fairness, clarity, and state autonomy over strict ideological loyalty has led to surprising alignments with the Court’s liberal wing in key cases. This analysis delves into her trajectory, highlighting when and how she has shifted toward moderation, while also underscoring where she has remained steadfastly conservative. Through her opinions and votes, Barrett emerges as a justice who is both principled and pragmatic, navigating the complexities of the law with a nuanced and independent voice.

Movements Over Time

This section was assembled using a language model to identify the most ideologically latent language in Justice Barrett’s 50 opinions (majority, concurring, or dissenting) authored between the 2020 and 2023 terms. She has yet to author an opinion this term. I then used the Supreme Court Database to track this language by case and the changes over time and by case issue area to both note the development of linguistic choices in her opinions and her positions on certain issues.

Environment

Justice Barrett’s views on environmental regulation reflect a noticeable shift from early skepticism toward agency power to a more deferential stance over time. In her early years, Barrett showed a conservative reluctance to expand agency authority. For instance, in HollyFrontier (2021), she dissented against the Court’s broad reading of the EPA’s waiver authority, arguing that “The Court’s contrary conclusion caters to an outlier meaning of ‘extend’ and clashes with statutory structure.” This reflected her strict textualist approach, limiting agency discretion to clear statutory boundaries. Similarly, in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service v. Sierra Club (2021), Barrett focused more on procedural compliance than defending strong environmental protections, noting that if the EPA’s rule didn’t adequately safeguard species, “it would jeopardize species protected under the Endangered Species Act of 1973,” but she ultimately deferred to the agency’s conclusion that the rule was unlikely to harm them.

By 2024-2025, however, Barrett’s opinions began showing a shift toward supporting greater agency deference. In Ohio v. EPA (2024), she criticized the Court’s decision to block an EPA rule without fully engaging with legal and procedural requirements, stating, “The Court today enjoins the enforcement of a major Environmental Protection Agency rule… without fully engaging with both the relevant law and the voluminous record.” Here, she emphasized the EPA’s statutory mandate to protect public health under the Clean Air Act, signaling a departure from her earlier scrutiny of agency discretion. In City and County of San Francisco v. EPA (2025), Barrett dissented in favor of the EPA’s authority to impose receiving water limitations under the Clean Water Act, arguing that such limitations were “useful when EPA issues general permits to broad categories of dischargers,” and pushing back against the majority’s restrictive interpretation of the statute.

This evolution suggests a growing pragmatism in Barrett’s approach to environmental regulation. While she initially adhered to a more rigid textualist and deregulatory stance, her later dissents reflect a more nuanced view of agency authority, occasionally aligning with the Court’s liberal justices.

Immigration

Barrett’s opinions in the area of agency deference specific to immigration cases have evolved, reflecting a preference for judicial restraint and a pragmatic approach to standing and executive authority. In Biden v. Texas (2022), she emphasized deferring to lower courts, criticizing the Court’s rushed timeline and its adoption of an untested jurisdictional theory. Her concern over premature judicial intervention suggests a conservative reluctance to expand judicial power in immigration policy.

By United States v. Texas (2023), Barrett’s skepticism toward broad standing claims became more evident. She questioned the applicability of past precedents and stressed that standing should hinge on redressability rather than abstract constitutional concerns. This pragmatic stance aligns with her broader reluctance to judicially second-guess executive enforcement decisions.

In Department of State v. Munoz (2024), Barrett reinforced executive discretion in immigration, asserting that admission decisions are a sovereign function largely immune from judicial control. Her statement that citizens lack a fundamental right to their noncitizen spouses’ admission underscores a formalist approach, limiting constitutional protections in immigration cases.

Over time, Barrett’s position has remained largely conservative, prioritizing executive and resisting expansive judicial intervention. However, her increasing emphasis on pragmatic standing analysis suggests a shift toward refining, rather than outright restricting, access to the courts in such disputes.

Other Agency Cases

Barrett’s language in Minerva Surgical (2021) and Corner Post (2024) suggests an evolution in her approach to agency deference in the opposite direction in non-environmental cases. While she has consistently emphasized textualism, her more recent writings indicate a growing skepticism toward agency power, particularly when agencies seek to impose procedural barriers or administrative burdens beyond what the statute clearly prescribes.

In Minerva Surgical, Barrett focused on the absence of statutory language supporting a judicial doctrine, reinforcing a strict textualist approach: “The Patent Act of 1952 sets forth a comprehensive scheme… But it nowhere mentions the equitable doctrine of assignor estoppel.” Similarly, she dismissed arguments for implied congressional ratification, stating that “Congress ratifies a judicial interpretation in a reenacted statute only if two requirements are satisfied,” emphasizing that statutory meaning must be explicitly grounded in legislative text.

By Corner Post, Barrett applied this textualist reasoning to agency actions, showing increased skepticism toward administrative interpretations that impose procedural barriers. She rejected arguments for agency-imposed limitations on lawsuits, holding that an APA plaintiff’s right of action “accrues” when the plaintiff is actually injured, rather than when the agency first acts. Her statement that “pleas of administrative inconvenience… never justify departing from the statute’s clear text” signals a shift away from deferring to agencies when they claim procedural efficiency or practical necessity.

Statutory Interpretation More Broadly

Justice Barrett’s approach to statutory interpretation consistently reflects her textualist philosophy and judicial restraint, with a focus on the plain text of statutes and a reluctance to expand their scope beyond what is clearly written. In cases like Viking River Cruises v. Moriana (2022), she reinforced this commitment by agreeing with the majority that “PAGA’s procedure is akin to other aggregation devices that cannot be imposed on a party to an arbitration agreement,” emphasizing her belief in following established precedent and judicial restraint. Similarly, in George v. McDonough (2022), Barrett underscored the importance of legal stability, arguing that “the correct application of a binding regulation does not constitute ‘clear and unmistakable error’… even if that regulation is subsequently invalidated.” This highlights her preference for limiting retroactive changes unless explicitly directed by Congress.

Barrett’s adherence to textualism is further evident in her decisions in ZF Automotive US, Inc. v. Luxshare, Ltd. (2022) and Boechler v. Commissioner (2022), where she firmly rejected broader interpretations of statutes. In ZF Automotive, she noted, “private entities do not become governmental because laws govern them and courts enforce their contracts,” reflecting her view that statutes should not be extended to include entities not clearly designated by Congress. In Boechler, she emphasized deference to Congress’s intent, arguing that the Court should not extend exceptions like equitable tolling beyond what the law explicitly allows, despite its traditional role in American jurisprudence.

In Arellano v. McDonough (2023), Barrett continued to apply this philosophy, rejecting the idea of expanding equitable relief. She pointed out that while “Congress could have designed a scheme that allowed adjudicators to maximize fairness,” it instead chose rules that prioritize “efficiency and predictability,” reinforcing her view that judicial interpretation should not alter legislative design. Similarly, in Bittner v. United States (2023), Barrett adhered strictly to the text of §5314, rejecting concerns over harsh outcomes and insisting that the Court’s error was conflating different reports referenced in the statute. Her firm stance on following textual clarity over potential inequities illustrates her broader approach of favoring statutory precision over judicial discretion.

Across these cases, Barrett’s consistent conservative stance on statutory interpretation remains evident, with no noticeable moderation. Her commitment to textualism, judicial restraint, and deference to Congress’s intent shapes her approach to statutory cases, where she generally resists expansive interpretations and favors narrow readings of the law as written.

Criminal Law

Barrett’s opinions in criminal law and procedure reflect a consistent textualist approach, evolving over time to balance statutory interpretation with concerns about fairness, judicial overreach, and government power limits. Early in her tenure, she was skeptical of broad legislative intent arguments and aggressive judicial oversight, but in more recent cases, she increasingly questions government overreach, especially in criminal prosecutions. This shift indicates a growing moderation in her approach as she refines her stance on balancing judicial restraint and government power.

In Wooden v. United States (2022), Barrett joined the Court in limiting the Armed Career Criminal Act (ACCA), criticizing reliance on legislative history and a Solicitor General’s brief. She dismissed it, saying, “the Court glosses this statute by leaning on weak evidence of Congress’ impetus.” This reinforces her textualist focus on statutory language over external materials.

In Van Buren v. United States (2023), Barrett expressed skepticism about overcriminalization, rejecting a broad reading of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. She warned that it would turn “millions of otherwise law-abiding citizens into criminals,” signaling a shift toward limiting prosecutorial overreach and ensuring criminal laws don’t exceed their intended scope. This reflects a more moderate concern for the balance between law enforcement and individual rights.

In United States v. Tsarnaev (2022), Barrett criticized judicial overreach, questioning appellate courts’ supervisory power. She noted her “skepticism that the courts of appeals possess such supervisory power,” arguing they should only review lower court decisions for legal errors, not impose procedural mandates. This highlights her commitment to judicial restraint, a principle that is moderately consistent with her increasing caution toward judicial activism.

By 2024, in Fischer v. United States, Barrett’s concerns about government overreach were even more pronounced. She criticized the Court’s decision to narrow a federal obstruction statute, calling it “textual backflips” and arguing the Court failed “to respect the prerogatives of the political branches.” This marks a moderation in her approach, as she moves from initially cautious views on judicial restraint to actively defending congressional intent and statutory breadth, even when upholding broad criminal statutes.

Specific to Death Penalty

Justice Barrett’s opinions in Nance v. Ward (2022) and Glossip v. Oklahoma (2025) reflect a consistent adherence to traditionally conservative judicial principles, particularly in her emphasis on federalism, judicial restraint, and deference to state authority in death penalty cases. However, her reasoning in Glossip suggests an even stronger commitment to these values over time, reinforcing a more rigidly conservative stance on the limits of federal court intervention.

In Nance, Barrett’s dissent was grounded in a conservative vision of state sovereignty and procedural formalism. She argued that “the law has long recognized a sovereign’s interest in mandating a particular form of capital punishment” and criticized the majority for bypassing habeas requirements in favor of §1983. Her assertion that habeas statutes “funnel such challenges to the state courts—which are, after all, ‘the principal forum’ for them” aligns with conservative skepticism toward federal overreach and a preference for state control over criminal justice matters.

By Glossip, her position had evolved into an even more forceful articulation of conservative judicial restraint. She dissented from the Court’s decision to reassess factual findings, arguing that “it is not our role to find facts” and cautioning against displacing the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals (OCCA). Her statement that “the Court has both displaced the OCCA as factfinder and potentially overridden state-law constraints” underscores a deeper commitment to limiting federal power, reinforcing a conservative preference for strict appellate boundaries and minimal interference in state death penalty cases.

Federalism

Justice Barrett’s views on federalism and sovereignty reflect a strong respect for state and tribal autonomy, with an emphasis on limiting federal power, though her approach has shown moderation in some cases.

In PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey (2021), Barrett defended state sovereign immunity as a core constitutional feature, stating, “State sovereign immunity indisputably makes it harder for Congress to accomplish its goals, as we have recognized many times before. This inhibition of Congress is not, however, a reason to set sovereign immunity aside.” She rejected arguments that states had surrendered immunity to private suits, affirming a strict textual interpretation that protects state rights.

Barrett’s views on tribal sovereignty in Denezpi v. United States (2022) mirrored her commitment to preserving autonomy, stating, “When a tribe enacts criminal laws, then, it does so as part of its retained sovereignty and not as an arm of the Federal Government.” She emphasized the distinctiveness between tribal and federal power, reinforcing the separation of sovereignties.

In Florida v. Georgia (2021), Barrett showed more moderation, acknowledging that Florida’s claim involved a serious burden on state interests, with the Court noting the claim was “much greater” than a typical injunction. This reflects her pragmatic approach, balancing state rights without unduly favoring one party.

In National Pork Producers Council v. Ross (2023), Barrett also showed moderation, questioning the burden California’s regulations placed on other states. She noted, “None of our Pike precedents requires us to attempt such a feat,” reflecting a nuanced approach that weighs moral considerations alongside practical implications.

In Cruz v. Arizona (2023), Barrett expressed deference to state court decisions, stating, “Given the respect we owe state courts, that is not a conclusion we should be quick to draw.” This reflects her balanced stance on respecting state institutions’ role in interpreting both state and federal law.

Overall, Barrett’s early decisions showed a conservative commitment to sovereign immunity and the separation of sovereignties, but her later rulings reflect a more balanced and pragmatic view, acknowledging the complexities of competing state and federal interests. This evolution suggests her approach is not purely conservative but adaptable when needed.

Executive Power

Justice Barrett’s opinions on executive power reflect a conservative, restrained approach that seeks to maintain a clear balance of authority among the branches of government while protecting the independence of the executive. In Trump v. Anderson (2024), she underscored the importance of limiting state authority over federal matters, noting that “States lack the power to enforce Section 3 against Presidential candidates,” reflecting her conservative belief in preserving federal supremacy in matters related to the presidency. Barrett also emphasized the importance of judicial restraint, stating, “This is not the time to amplify disagreement with stridency,” signaling her preference for stability and minimal disruption, especially during politically sensitive periods.

In Trump v. United States (2024), Barrett reinforced the protection of executive powers, asserting that “The Constitution prohibits Congress from criminalizing a President’s exercise of core Article II powers.” Her support for the President’s ability to challenge criminal statutes related to official acts aligns with her view that executive authority should be shielded from excessive judicial interference, especially when it could jeopardize the executive’s independence. She acknowledged that while Presidents are not immune from criminal liability, “any statute regulating the exercise of executive power is subject to a constitutional challenge,” indicating her commitment to ensuring that executive power is not unduly constrained by legislative overreach.

Religion and Abortion

Justice Barrett’s jurisprudence on religion and abortion reflects a consistently conservative approach, though with some nuance in her reasoning. In Fulton v. Philadelphia (2021), she voiced skepticism about overruling Employment Division v. Smith, questioning whether replacing it with strict scrutiny would be practical: “But I am skeptical about swapping Smith’s categorical antidiscrimination approach for an equally categorical strict scrutiny regime, particularly when this Court’s resolution of conflicts between generally applicable laws and other First Amendment rights—like speech and assembly—has been much more nuanced.” While acknowledging religious liberty’s historical significance, she found “the historical record more silent than supportive” regarding broad First Amendment exemptions from generally applicable laws. She also questioned whether religious entities should receive different treatment than individuals, asking, “Should entities like Catholic Social Services—which is an arm of the Catholic Church—be treated differently than individuals?” This measured approach signaled her reluctance to radically expand religious exemptions while still reinforcing the importance of Free Exercise protections.

Her rulings in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022) and Carson v. Makin (2022) further affirmed her commitment to religious liberty, consistently siding with the Court’s conservative majority in striking down restrictions on religious expression. In Kennedy, she joined the majority in upholding a public school football coach’s right to engage in postgame prayer, aligning with a broader shift toward dismantling rigid Establishment Clause barriers. Similarly, in Carson, she backed the decision requiring Maine’s tuition assistance program to include religious schools, reinforcing the principle that states cannot exclude religious institutions from public benefits solely based on their religious status. These cases reflect Barrett’s preference for a nuanced, case-by-case approach to Free Exercise claims rather than an automatic strict scrutiny standard.

On abortion, her rulings in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) and Moyle v. United States (2024) reflect an unwavering deference to state power. In Dobbs, she joined the majority in overturning Roe v. Wade, effectively removing federal constitutional protections for abortion and returning the issue to state legislatures. Her stance in Moyle continued this trajectory, where she framed Idaho’s restrictive abortion law as a legitimate state interest, emphasizing that it “criminalizes the performance of most abortions.” She also raised concerns about the federal government’s interpretation of EMTALA, cautioning against transforming emergency rooms into “federal abortion enclaves governed not by state law, but by physician judgment.” However, she acknowledged the government’s narrower application of EMTALA, noting that its reach was “far more modest than it appeared when we granted certiorari and a stay.”

Speech

Justice Barrett’s 2024 First Amendment opinions reflect an ideological approach that blends skepticism of broad government intervention with a restrained view of constitutional protections. She consistently avoids rigid doctrinal rules, favoring a case-by-case analysis that limits judicial overreach while still recognizing the expressive rights of individuals and corporations.

Her views on corporate speech in Moody v. NetChoice and Murthy v. Missouri reveal a pragmatic conservatism: she affirms that editorial choices—whether made by humans or AI—can be protected, yet she questions whether algorithmic decisions alone qualify as inherently expressive. She also resists expansive claims of government coercion in platform moderation, reinforcing a narrower interpretation of state action. This approach aligns with a conservative preference for limiting judicial intervention in market regulations while protecting corporate First Amendment rights.

At the same time, Barrett’s opinion in Vidal v. Elster reveals a nuanced stance on judicial methodology. She challenges the Court’s reliance on history as a decisive factor, warning that “a rule rendering tradition dispositive is itself a judge-made test.” This suggests an ideological inclination toward textual and functional interpretations rather than strict originalism. Similarly, in Lindke v. Freed, she demands a clear tie between state authority and speech restrictions, reflecting a hesitancy to expand First Amendment protections to claims lacking concrete governmental involvement.

Taken together, Barrett’s positions illustrate a restrained but ideologically consistent conservatism. She prioritizes limiting judicial interference in both government and private actions, applies a selective defense of speech rights, and remains skeptical of broad constitutional claims that could expand regulatory or judicial power.

Second Amendment and Other Constitutional Protections

Barrett’s approach to constitutional rights, particularly the Second Amendment, taxation, and property rights, reflects a consistent originalist methodology, though her application has evolved over time. In Bruen (2022), she strictly adhered to historical benchmarks, rejecting reliance on Reconstruction-era laws to interpret the Second Amendment. She warned against “freewheeling reliance on historical practice from the mid-to-late 19th century” and stressed that “postenactment history” should not be given undue weight, reinforcing a rigid, textually grounded originalism.

By Rahimi (2024), however, Barrett showed a more flexible application of originalist principles. While reaffirming that constitutional meaning is “fixed at the time of its ratification,” she acknowledged the dangers of a “law trapped in amber” and argued that historical regulations should “reveal a principle, not a mold.” Her reasoning in upholding firearm restrictions for domestic abusers suggests an evolving willingness to balance historical fidelity with contemporary policy concerns.

In Moore (2024), Barrett maintained a formalist approach to taxation, emphasizing that the Sixteenth Amendment requires “realized” income and rejecting the government’s attempt to expand the definition. She framed the distinction between income and direct taxes as firmly rooted in constitutional text and precedent, cautioning against broad congressional power in taxation without clear historical support.

Her stance in Sheetz (2024) similarly underscored a strong commitment to property rights, rejecting legislative exemptions from takings rules. She insisted that “nothing in constitutional text, history, or precedent” supports such exceptions, reinforcing that government-imposed permit conditions must have an “essential nexus” to land-use interests.

While Barrett’s jurisprudence remains grounded in conservative originalism, her approach has shifted from a rigid historical framework in Bruen to a more principle-driven methodology in Rahimi. This suggests a maturing judicial philosophy that remains ideologically conservative but is increasingly pragmatic in application, particularly when historical precedent risks undermining core constitutional protections.

Other Agenda Items

Justice Barrett’s opinions in cases involving economic regulation and jurisdictional issues reflect her consistent textualist approach, prioritizing clear constitutional limits and procedural safeguards. In Goldman Sachs (2021), she reinforced the Basic presumption in securities fraud litigation, stating, “the defendant bears the burden of persuasion to prove a lack of price impact,” highlighting her adherence to established procedural fairness. Similarly, in Babcock v. Kijakazi (2022), she emphasized the progressive nature of the benefits formula, rejecting broader claims that would exceed congressional intent, noting, “the formula is progressive in that it awards lower earners a higher percentage of their earnings.”

In jurisdictional matters, Barrett’s views evolved to express concern over manipulation of legal principles. In Mallory v. Norfolk Railway (2023), she dissented, stressing the importance of preserving constitutional limits on personal jurisdiction, asserting, “States may now manufacture ‘consent’ to personal jurisdiction,” which risks undermining due process protections. This shift reflects her growing concern about how legal doctrines are stretched for tactical gain. Similarly, in Acheson Hotels (2023), Barrett emphasized standing requirements, remarking, “Only plaintiffs who allege a concrete injury have standing to sue in federal court,” and expressed reluctance to reconsider established procedural rules, underscoring her focus on protecting legal structures from manipulation.

Together, these cases reveal Barrett’s conservative, structured approach to both economic regulation and jurisdiction, with an increasing emphasis on limiting judicial discretion and safeguarding constitutional principles.

Takeaways

Justice Barrett’s rulings on key issues, particularly abortion, federalism, and gun rights, reveal her strong conservative principles, despite some criticisms suggesting she isn’t conservative enough. In Dobbs v. Jackson (2022), Barrett played an essential role in overturning Roe v. Wade, advocating for returning the abortion issue to state legislatures. Her approach in this case aligns with conservative views on limiting federal power and restoring state autonomy. Similarly, her position in Moyle v. United States (2024), which upheld Idaho’s restrictive abortion law, demonstrated her consistent belief in empowering states to regulate abortion according to their own policies.

Her stance on federalism is also firmly conservative. In PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey (2021), Barrett supported a decision that protected state sovereignty, ruling against a federal law that would have allowed a private company to condemn state-owned land for a pipeline project. This decision reinforced her commitment to limiting federal overreach and protecting state authority. In Florida v. Georgia (2021), while Barrett balanced the interests of the federal government and state sovereignty, she ultimately sided with a more cautious approach, considering the states’ significant interests in the case.

Barrett’s approach to Second Amendment rights also illustrates her conservative leanings. In Rahimi (2024), she ruled on a case involving restrictions on firearms for individuals with domestic violence orders of protection, applying a historical analysis of the Second Amendment. While some criticized her for not taking a stricter originalist approach, her ruling still emphasized the need for historical context in understanding gun rights, balancing personal freedoms with the evolving nature of legal interpretation.

These cases highlight that Justice Barrett’s conservatism is not merely symbolic, but rather evident in her consistent application of principles that limit federal power, protect state rights, and defend individual liberties. Critics who claim she isn’t sufficiently conservative miss the nuances in her approach. Barrett blends strong conservative ideology with a pragmatic flexibility, making her a reliable conservative justice without being overly rigid in her rulings.

These cases highlight that Justice Barrett’s conservatism is not merely symbolic, but rather grounded in her consistent application of principles that limit federal power, protect state rights, and defend individual liberties. However, her rulings also demonstrate a pragmatic approach to the law. While she remains steadfast in her conservative convictions, Barrett shows flexibility in interpreting the Constitution, considering the broader implications of her decisions, and balancing legal precedents with evolving societal needs.

[This previously ran on Legalytics Substack]

Read more from Empirical SCOTUS here….

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. Check out more of his writing at Legalytics and Empirical SCOTUS. For more information, write Adam at [email protected]. Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.