Your Crappy eDiscovery Tool Could Cost You Your Career

You owe it to yourself to vet the tools you’re using, consider what they’re missing, and what that could mean for your company, your clients, or your career.

Hypothetical question: What if the tool you were using to process and review documents was missing more than 90% of the evidence you were responsible for producing? You feed the program 10 emails, nine of which vanish without a trace. Seems improbable, but just play along for the sake of argument. How would that affect the quality of your production? How would it impact your ability to conduct a “reasonable” search under Rule 26? And whose neck would be on the line when an opposing party complains to the judge that, um, Your Honor, there appears to be a huge freaking hole in this production.

Hypothetical question: What if the tool you were using to process and review documents was missing more than 90% of the evidence you were responsible for producing? You feed the program 10 emails, nine of which vanish without a trace. Seems improbable, but just play along for the sake of argument. How would that affect the quality of your production? How would it impact your ability to conduct a “reasonable” search under Rule 26? And whose neck would be on the line when an opposing party complains to the judge that, um, Your Honor, there appears to be a huge freaking hole in this production.

This would be a tight spot for any lawyer. Luckily, most people are oblivious to the fact that most legacy eDiscovery “solutions” fail to capture a huge amount of the content fed to them, and many opposing parties are likely just as unsophisticated. Others are probably aware of this fact but feign naïveté for the larger good. It’s like, “Hey, we’re all using black boxes. If you don’t challenge mine, I won’t challenge yours.”

The problem is that, as proficient technology becomes more widely available and standards for competence rise, these excuses (ignorance) and allowances (looking the other way) no longer fly.

Curbing Client And Talent Loss With Productivity Tech

It seems hard to believe that, in 2016, widely used eDiscovery and document processing tools are failing to capture large swaths of content — read: potential evidence — fed to them. But that’s exactly the case.

To be sure, many tools at least flag the files they are unable to read in exception reports, those maddeningly long, inscrutable documents that identify the exact file that failed and, sometimes, the reason for the failure.

But, sometimes, large chunks of information just evaporate into thin air. Evidence gone, with no record it ever existed in the first place.

Just… poof.

Sponsored

Happy Lawyers, Better Results The Key To Thriving In Tough Times

Curbing Client And Talent Loss With Productivity Tech

Law Firm Business Development Is More Than Relationship Building

AI Presents Both Opportunities And Risks For Lawyers. Are You Prepared?

Consider the following real-world example, pulled from the Enron dataset.

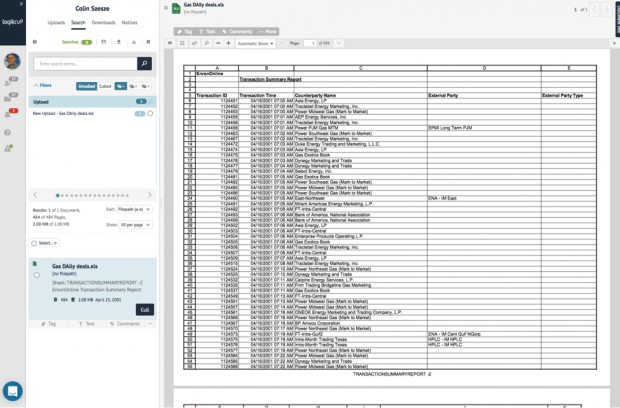

Here is a spreadsheet titled “Gas Daily deals,” which shows transactions of natural gas stocks. The file was originally included in the Enron dataset as an email attachment. Below, it appears in Logikcull after having been extracted from the email, indexed, imaged, and so forth. You can click to enlarge.

Notice a couple things. First, the document is 484 pages long, as shown by the light blue box on the left. Second, it is formatted in the document view in a way that closely resembles the original, native file. That original document has been imaged and OCR’d, and all of its associated metadata has been preserved and captured so as to be made findable via text search.

Now look at the following document, processed by a popular eDiscovery vendor.

Sponsored

How The New Lexis+ AI App Empowers Lawyers On The Go

AI Presents Both Opportunities And Risks For Lawyers. Are You Prepared?

Download document as captured by eDiscovery tool.

Now this is pretty insane and probably more than a smidge malpractice-y. It is the exact same document, but, as it has been presented for review, is only 12 pages long. Not 484 pages. Twelve. In other words, the eDiscovery tool used to process the spreadsheet above captured approximately 2% of the information that was actually there. The other 472 pages of potential evidence have vanished into the ether.

Now, in this instance, the reason for the disparity in the presentation of the documents is fairly straightforward. Logikcull captures and extracts hidden fields. The other tool does not. But if this strikes you as a fringe case, consider that this lesser tool also has trouble processing basic file types, like Word and PowerPoint documents, as its exception report indicates. This could potentially be due to file corruption, file mismatch, the size of the document (it doesn’t process Excel spreadsheets larger than 1,000 PDF pages, for example), or simply because the processing engine couldn’t account for certain common file types. But in any case, about 6,000 of 40,000 total documents in the Enron corpus fed to this tool did not appear in the searchable review set.

The scary thing is that this is the industry norm, and nobody seems to care. But certainly, if a superior, affordable solution exists, attorneys have a duty to their clients and as officers of the court to find and use them. Courts have never demanded perfection in discovery, but they do demand diligence. Parties must, according to the Rules, make a “reasonable effort to assure that the client has provided all the information and documents available to him that are responsive to the discovery demand.” Does taking a chance you’re missing half the stuff that’s actually there seem “reasonable”? Not to us.

Certainly, then, using tools that fail to capture much of this information, or capture that data inaccurately, has deep, direct consequences on the ability of parties to fulfill their obligations under the law — and, therefore, has implications for sanctions and malpractice. Such failures have cost high-profile attorneys and their clients dearly. Look no further than the closely watched Coquina vs. TD Bank case from four years ago, where a key document presented at trial by lawyers for TD turned out to be devoid of critical information appearing on the original version of the document — which subsequently surfaced in a separate case. That mistake ended a career.

The importance of “processing” gets overlooked due to its highly technical nature and the way in which it’s described (by eggheads) in the context of the EDRM, as a chore that must be completed to get to the important stuff: search and review. But the fact is, processing is among the most essential to revealing what the evidence actually says, and the easiest to get wrong. That’s why it took Logikcull years to get it right. You don’t automate the 3,000+ essential processing steps overnight.

It is unacceptable, given the advances in technology, that the vast majority of eDiscovery tools are routinely missing large chunks of potentially discoverable information. If you’re reading this, now you know, and you owe it to yourself to vet the tools you’re using, consider what they’re missing, and what that could mean for your company, your clients, or your career.