There are some things you know you should do, and always mean to do, but never seem to get around to doing. For me that’s donating blood. I am not squeamish about needles or anything—if there’s a vaccination out there, I’m a willing human pincushion—but it’s just never happened. An unscientific sampling of my friends—a number of whom are also busy professionals—indicates that this task has also long been on their to-do lists. (One pal cited the macabre notion of having a vital fluid drained from one’s body by a machine as a cause for hesitation.)

There are some things you know you should do, and always mean to do, but never seem to get around to doing. For me that’s donating blood. I am not squeamish about needles or anything—if there’s a vaccination out there, I’m a willing human pincushion—but it’s just never happened. An unscientific sampling of my friends—a number of whom are also busy professionals—indicates that this task has also long been on their to-do lists. (One pal cited the macabre notion of having a vital fluid drained from one’s body by a machine as a cause for hesitation.)

Meanwhile, we are walking around wasting perfectly good blood that could help save another person’s life. As soon as I scheduled an appointment to donate, that reality became even more clear, as the world we live in seems to have been turned upside down and shaken around.

The good news, I discovered, is that if you want to give blood, there is very likely a blood drive near you ready and willing to take it. In fact, on my way to work today, I noticed a mobile donation bus a couple of blocks from my office. It’s the kind of thing you don’t notice until you start looking.

Meet Me At ILTACON: Opus 2 And AI Workbench

Swing by Booth 800 for a look at the latest in AI-powered case management.

I scheduled an online appointment through the University of Washington, my alma mater (go Huskies!). I showed up and was given a health-screening questionnaire on an iPad. I know the process is intended to ensure that the blood supply is squeaky clean, but the inquiries really seemed to be designed to simply weed out anyone with a good story to tell: no prostitutes, no recent incarceration, no tropical travel, no back-alley tattoos, no aspirin. And no gay sex for men after 1977.

(Side rant: The FDA banned sexually active gay men from donating blood in 1983, when the AIDS crisis was gripping the nation. The ban festered under the radar until the FDA overturned the ban in late December of last year. Now the FDA allows donation 12 months after your last sexual contact with another man—a change that is in the process of being implemented by donation centers in my state. Yay! A reason to celebrate a yearlong dry spell.

This less-stringent ban still reeks of pointless discrimination in my sensitive nostrils, especially given that all donated blood is screened for HIV already. (HIV transmission rates from blood transfusions in the U.S. are currently 1 in 1.47 million.) It effectively still bans most gay men from donating, functionally saying: “Sure, you can donate now, but first you have to give up sex—a basic human need and activity—for a year of your life.” As a woman, I can bang every straight guy I encounter on the street and still donate, but the mayor of my city—a married gay man in a 25-year relationship—cannot. It makes no sense.)

Okay, back to me and my blood. After filling out the questionnaire, I was informed that my breakfast cereal and milk provided insufficient hydration and sodium, so I was sent to the snack area to consume a morning bag of potato chips and water. This marked the first time I ever struggled to eat chips.

Skills That Set Firms Apart

Legal expertise alone isn’t enough. Today’s most successful firms invest in developing the skills that drive collaboration, leadership, and business growth. Our on-demand, customizable training modules deliver practical, high-impact learning for attorneys and staff—when and where they need it.

Then they tested my iron level by sticking my finger with a needle, as a sort of opening act for the real show. They assured me that the actual blood draw would hurt less, which I assumed was probably a lie they told newbies like me to keep us from running away screaming. Anyway, it worked, and they led me to this chair that looked like a component of a modern-day torture chamber.

I took a seat and they examined my arm veins. I was notified that I had “good veins” for donation. I was unduly proud of this until they informed me it just had to do with hydration and genetics. (Although the fact that I was hydrated after drinks out with a client the night before was a nice surprise.) I learned that dehydrated people’s blood is thick and sluggish like molasses and overfed sloths.

The technician kindly put a disposable towel over me in case blood sprayed everywhere—a precautionary measure whose needlessness left me weirdly disappointed. Then she stuck the needle into my arm. The feeling of having the needle in there was like receiving a constant pinch from a mean girl in middle school who slightly relaxes her grip over time. I snuck a peek: The junction where the needle met my skin was pretty freaky looking. But she covered it up with a gauze pad and had me focus on squeezing this little stress ball shaped like a brain.

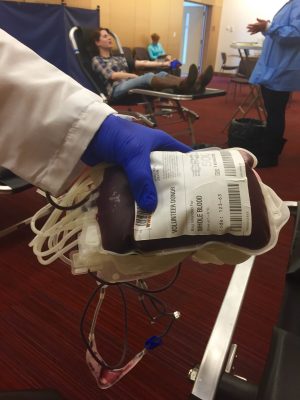

I heard that donating makes you fatigued, so I laid back and waited for the life force to drain from my body. In only about 15 minutes it was over, and they sent me off with an arm wound in first-aid tape that color-coordinated with my outfit. My passive efforts had resulted in a bag of blood that looked so large it couldn’t possibly have come from my body without resulting in my death. I felt like I should have looked like one of those desiccated human husks left behind after an alien spider attack in a movie, but I felt fine. (In reality, they siphoned only one of my body’s 13 or so pints of blood.)

I was cast off to the snack area for a 10-minute wait to ensure I didn’t pass out or anything. I helped myself to a Gatorade and cookies in an attempt to replace my lost body mass with processed garbage, and was encouraged to take stuff for the road. The snack table is an unsung treasure in the blood-donation experience.

After I got to work that day, I felt like I was in a bit of a fog but not exhausted. I did lose the ability to support the weight of my own head during a two-hour conference call, but it was Friday and such a circumstance is typical by the end of the week. I wanted to go to bed right after I got home from work, but instead I went out to dinner with friends and then stayed up past midnight. (Scientific observation: Donating blood does not appear to accelerate alcohol intoxication, at least after eating a pile of delicious Indian food.)

I would definitely donate blood again, which you can do every two months. The ban on sexually active gay men is an insulting throwback that I find to be ridiculous, but it won’t stop me from donating. That would be like saying: “I refuse to help save your life become someone in the federal government is stupid.” The experience was not as comfortable as, say, a trip to the spa, but you leave feeling like you did something good for the world. Save a life and get unlimited cookies? Sounds like a good deal to me.

Allison Peryea is a shareholder attorney at Leahy Fjelstad Peryea, a boutique law firm in downtown Seattle that primarily serves community association clients. Her practice focuses on covenant enforcement and dispute resolution. She is a longtime humor writer with a background in journalism and cat ownership. You can reach her by email at [email protected].