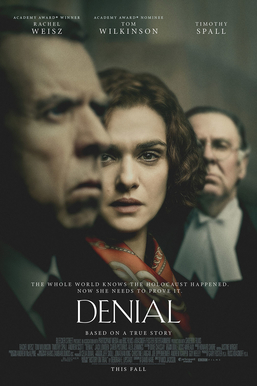

Would you like to watch a movie about a prominent bloviator who supports an authoritarian regime, has no regard for the truth, and attempts to stifle free speech? Believe it or not, I am referring a film that has nothing to do with the President-elect of the United States. Instead, I am talking about the 2016 film Denial, which tells the story of a lawsuit against a historian by a prominent Holocaust denier. Putting aside the parallels to Trump, Denial is a well-acted film that could have used tighter writing and directing.

Would you like to watch a movie about a prominent bloviator who supports an authoritarian regime, has no regard for the truth, and attempts to stifle free speech? Believe it or not, I am referring a film that has nothing to do with the President-elect of the United States. Instead, I am talking about the 2016 film Denial, which tells the story of a lawsuit against a historian by a prominent Holocaust denier. Putting aside the parallels to Trump, Denial is a well-acted film that could have used tighter writing and directing.

The defendant in the lawsuit is Deborah Lipstadt (Rachel Weisz), a prominent Holocaust historian based in Atlanta. As the film opens, Lipstadt is confronted by David Irving (Timothy Spall), a British historian and Holocaust denier, who claims that there is no evidence that Auschwitz was a death camp or that Hitler directed the genocide of so many Jewish people. Irving subsequently sues Lipstadt and her publisher after Lipstadt writes a book accusing Irving of deliberately ignoring evidence that the Holocaust exists. Despite the pro-plaintiff libel laws in England (unlike in the U.S., the burden is on Lipstadt to prove that her assertion is true), Lipstadt decides to fight Irving in court instead of settling, and hires prominent solicitor Anthony Julius (Andrew Scott) and barrister Richard Rampton (Tom Wilkinson) to defend her.

I am always happy to see Weisz pop up in a film, and she is strong as usual here, portraying Lipstadt’s passion that her scholarship is sound and that Irving is a fraud. She also displays frustration with what she sees as Julius and Rampton’s ignorance of the actual Holocaust victims. On the other hand, Weisz’s attempted Queens accent is inconsistent at best and mostly distracting (it is always odd to me when a mostly British production hires a fellow Brit to play an American).

Paying for Law School in 2025: A Straight-Talk Playbook

Juno has consistently secured the best private loan deals for students at the Top MBA programs since 2018—now they’re bringing that same offer to law students, at no cost. Students can check their personalized offers at juno.us/atl This article is for general information only and is not personal financial advice.

Wilkinson gives a terrific performance as Rampton. Wilkinson is typically hit or miss as an actor for me; he is great when he is understated (such as in In The Bedroom) but rarely succeeds when he gives a bigger performance (such as his caricatured gangster accent in Batman Begins). Here, Wilkinson finds a nice balance, displaying Rampton’s legal brilliance, his respect for Lipstadt, and his disdain for Irving despite his lack of social graces (such as smoking and swearing while visiting Auschwitz).

Spall is solid as usual, portraying Irving’s staunch belief that he is correct about Hitler. Spall smartly keeps Irving’s motivations close to the vest, never revealing whether Irving truly believes the bile he is spouting or whether it is just an act. And as mentioned above, given the events of early November, Spall’s performance – including the fact that he bears a resemblance to Trump – takes on a new meaning.

Denial is definitely an actors’ film, as the writing and direction leave something to be desired. The movie contains huge time jumps, and I was not always sure of how much time had elapsed since the previous scene. Chyrons displaying lines like “One Year Later” would have been helpful.

Similarly, the climactic trial is oddly paced. The narrative focuses on a few specific scenes without showing what was happening in between. As a result, I had no idea how the trial was actually going; the movie implies that important testimony is occurring but shows only short bits and pieces. The most egregious example of this occurs during the testimony of Professor Robert Jan van der Pelt (Mark Gatiss, also from Sherlock), a Holocaust professor and expert witness for the defendants. Irving launches into an angry diatribe against van der Pelt during cross-examination. But instead of letting van der Pelt answer Irving’s “question” (which van der Pelt had asked to do), the judge just adjourns the proceedings for the day and the film never returns to it. I do not know if it is common to take breaks during the middle of questions in England (it most certainly is not the normal practice in the United States), but this seemed very odd and a tactic to artificially create tension.

Further, Lipstadt has an oddly passive role in her defense. Lipstadt is not an attorney and thus does not know as much as Julius and Rampton about legal strategy. But there are many scenes in which Lipstadt criticizes a decision Julius or Rampton makes (such as not putting any Holocaust survivors or Lipstadt herself on the witness stand), Julius and Rampton telling Lipstadt that she is wrong, and then Lipstadt ultimately agreeing that they are in fact right. This may have been the way that things played out in reality, but it makes for poor drama for Lipstadt to never have a impactful moment during the trial, instead acting as a nuisance for the lawyers. It also veers into mansplaining territory.

Due to the aforementioned problems, I would not recommend going out of your way to see Denial, especially because there are so many terrific movies that have been released in the past three months (Arrival, Manchester by the Sea, and Moonlight are my three favorites of the year). But if you really want to see a film in which a country’s most brilliant minds work together to defeat a Trump-like figure, you are not going to do much better than Denial.

Harry Graff is a litigation associate at a firm, but he spends days wishing that he was writing about film, television, literature, and pop culture instead of writing briefs. If there is a law-related movie, television show, book, or any other form of media that you would like Harry Graff to discuss, he can be reached at [email protected]. Be sure to follow Harry Graff on Twitter at @harrygraff19.