Timelines are probably one of the most-used type of litigation graphic. Timelines are also one of the litigation graphics that litigators do wrong the most. The problem is usually two-fold: not knowing how to create them, and not knowing how to use them. We’ll look at Game of Thrones to teach us the latter point. For now, here’s a tool to help with point one.

Timelines are probably one of the most-used type of litigation graphic. Timelines are also one of the litigation graphics that litigators do wrong the most. The problem is usually two-fold: not knowing how to create them, and not knowing how to use them. We’ll look at Game of Thrones to teach us the latter point. For now, here’s a tool to help with point one.

This month, Microsoft announced a new tool for PowerPoint that can take a lot of the heavy lifting out of timeline creation. It’s only available for the subscription version of PowerPoint, even if you own the latest version of PowerPoint 2016. In essence, you can take a boring bullet point list and turn it into a timeline with a single click.

Here’s how you do it:

You can see here that I’ve created a bullet-point list of things. I did a couple of things on purpose – I put one thing out of order, I mixed up the format of dates, and I put a date as the event for the entry on July 4, 2010.

Once you start typing, PowerPoint’s Designer feature recognizes what you are typing as a list of dates and events and begins to suggest themes for you in a panel on the right.

As you can see, it does not automatically sort my dates by chronological order. You can see that it also gets confused with my entry for 4th of July. But that’s ok, because even though these things are now a series of text boxes on my screen and not an easy-to-edit bullet list, if I click on any entry, I get a little pop up window with my bullet-point list back.

I can’t drag one date/event group above or below another group, but it’s easy enough to edit by simply clicking in the box and changing the text.

Now, let’s talk about problem two – how you are using your timelines incorrectly.

Do Not ‘Game of Thrones’ Your Timelines

I’ll be honest, when I watched the second greatest episode of the show, The Battle of the Bastards, and I saw that Ramsay Bolton had kidnapped a Stark boy, I had no idea who that kid was. I had completely forgotten about his existence because apparently my brain can only hold the plotlines of the top 160 most important characters of that show in memory. I recently started to rewatch the whole series from the beginning and sure enough, he is in fact in 14 of the first 60 episodes. I had just forgotten about him. I had also forgotten about a number of other characters and details in the show. I love that show, but it throws a lot at you and you are juggling a lot of plotlines and characters and map locations in your head.

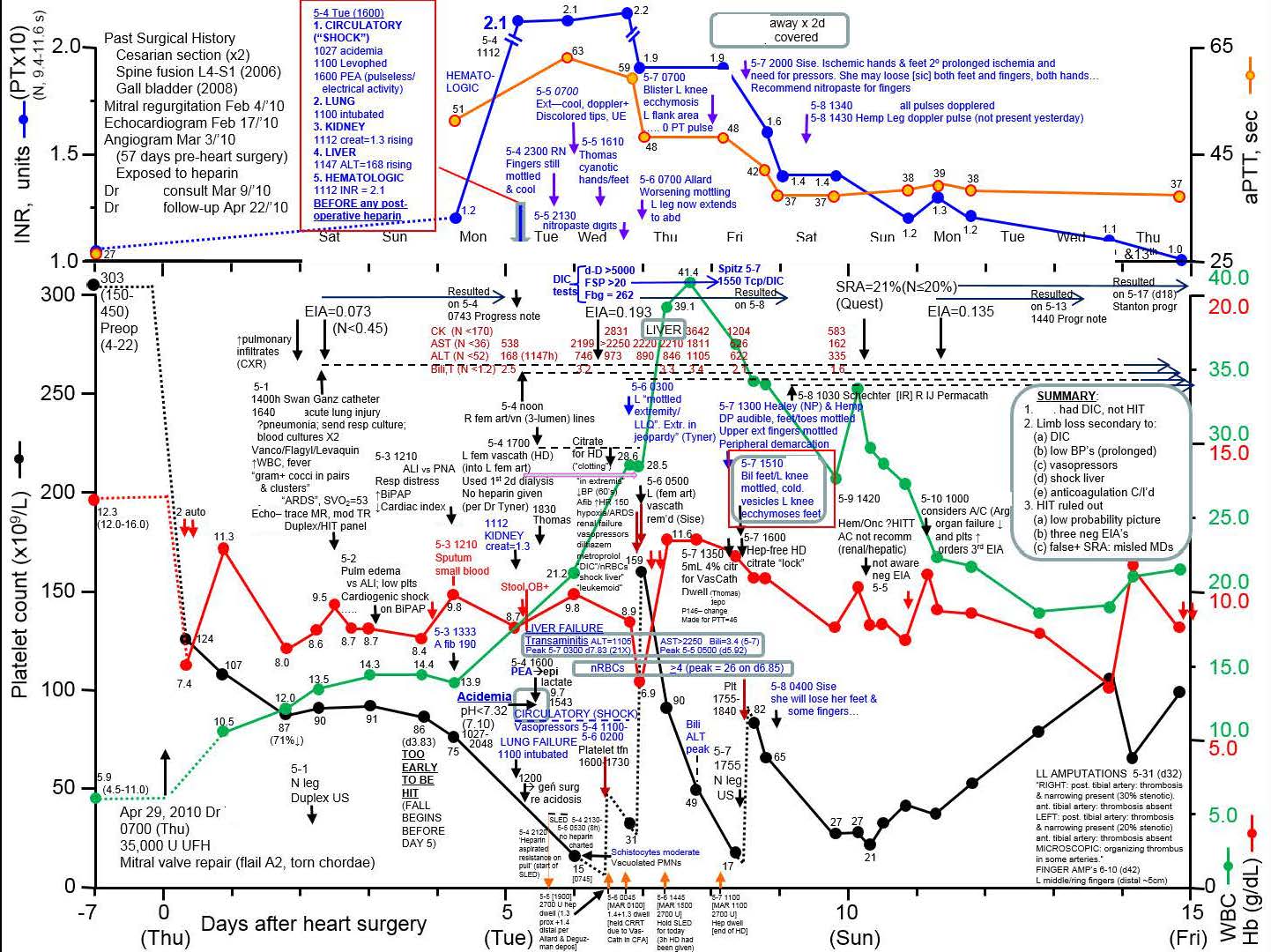

Lawyers do the same thing with timelines. Take, for example, this timeline that an attorney made in a case I recently worked on:

Or in a more extreme example, another timeline an attorney used in a case I worked on a few years ago:

Attorneys: Stop Trying to “Game of Thrones” your timelines. The problem comes from the common misunderstanding that the purpose of a timeline is to list a bunch of things in chronological order. That’s not what timelines are for. Timelines are a tool to do what you should be doing in your trial from start to finish – they should tell a story.

Nancy Duarte, a PowerPoint slide design guru, uses a three-second rule. If the audience can’t grasp the gist of your slide in three seconds, the slide is too complicated. Here’s how to apply that to litigation, and timelines in particular.

I was recently watching a workplace sexual harassment trial, and the defense put up a timeline of a sequence of about 15 different events of when the female employee plaintiff worked on projects with the employer. It included things like when certain inappropriate activities took place, and when plaintiff and defendant worked together on projects after each incident. It included specific dates and places and a brief description for each date. The purpose was to show how many times plaintiff chose to work on teams with defendant while these different events were happening to show that she was in fact not offended by the incidents.

It was a straight bar across the page with the 15 entries sticking out of the top and bottom. Even though the timeline was not as bad as the examples above, it contained a lot of extraneous information. For example, does it really matter the day of the month that something happened? Does the location matter? Does it matter what the project was that they worked on together? Really, the only thing that is important to the defense theme is that there were three or four different incidents, and while those were happening, plaintiff chose to work on the defendant’s team 10 different times. You could almost make the whole thing without any dates or words even. I was envisioning for that timeline a single bar going across the page with maybe four blue markers showing each incident, and 10 red markers showing each time plaintiff chose to work with defendant. If you build the whole thing out of symbols, you can flash it on the screen and the jury gets in in three seconds or less.

Conclusion

PowerPoint gets a lot of hate, and most of that is probably because it has so many tools that let you put something together fast. Once you’ve put something together fast, it’s easy to just move on. The result is a boring presentation. PowerPoint is a storytelling aid. Just because you can build a timeline in less than two minutes does not mean that you can finish a timeline in less than two minutes. To finish a timeline, you have to look at it, trim it, tweak it, simplify it, and practice with it. Give the jurors less facts to juggle. Otherwise, they are going to be back in the deliberation room thinking they can count all of the Stark siblings on one hand, even if you’ve mentioned Rickon Stark some 14 times in the past.

Jeff Bennion is a solo practitioner at the Law Office of Jeff Bennion. He serves as a member of the Board of Directors of San Diego’s plaintiffs’ trial lawyers association, Consumer Attorneys of San Diego. He is also the Education Chair and Executive Committee member of the State Bar of California’s Law Practice Management and Technology section. He is a member of the Advisory Council and instructor at UCSD’s Litigation Technology Management program. His opinions are his own. Follow him on Twitter here or on Facebook here, or contact him by email at [email protected].