In 2008, the Supreme Court decided Boumediene v. Bush, holding that “enemy combatants” at Guantanamo Bay enjoy the constitutional privilege of habeas corpus. Today, almost eight years later, Guantanamo Bay is still with us — and probably not going anyway anytime soon, given President Trump’s support for keeping it open.

In 2008, the Supreme Court decided Boumediene v. Bush, holding that “enemy combatants” at Guantanamo Bay enjoy the constitutional privilege of habeas corpus. Today, almost eight years later, Guantanamo Bay is still with us — and probably not going anyway anytime soon, given President Trump’s support for keeping it open.

So the legal and moral issues explored by Anton Piatigorsky in his novel Al-Tounsi, based on a fictionalized version of Boumediene and Guantanamo Bay, remain very relevant. That’s all the more reason for readers to pick up this excellent book. I concur with our resident book critic, Harry Graff, who praised Al-Tounsi as “an enjoyable, well-written exploration of the personalities behind the Supreme Court.” Specifically, the novel looks at how the messy personal lives of the justices affect their handling of a major, Boumediene-esque habeas corpus case.

How did Anton Piatigorsky come up with the idea for this book? I recently interviewed him about Al-Tounsi, his creative process, and his career as a writer.

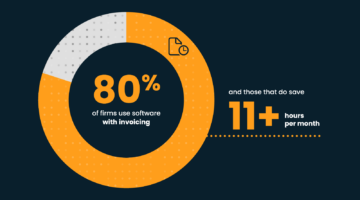

Billables Are Not The Same As Cash Flow. Here’s Why That’s Important.

Findings from the MyCase 2025 Legal Industry Report.

DL: Congratulations on Al-Tounsi, which is a great read. It’s also impressively accurate on the law — which is no small feat given that you are not a lawyer by training. Can you introduce yourself to our readers and say a bit about yourself?

AP: Thank you! I’m a playwright, novelist and librettist originally from the D.C. area, now Toronto. I studied religion in college, more as an anthropologist than a believer. As a writer I gravitate towards stories about people who work or live within secular systems that are similar to religion. So I’m fascinated by how judges and lawyers — like religious leaders — use a code of formal ideas and rituals to create meaning and identity for a community. For example, I once wrote a play about a young Jewish mystic in psychoanalysis, and my last book was a collection of historical stories about twentieth-century dictators when they were teenagers.

Al-Tounsi is my first novel about law, but I doubt it will be my last. There are countless potential characters and stories in legal-based fiction, so many ways that general ideas can be made concrete and dramatic.

DL: Our lawyer readers will notice — and you mention in your acknowledgements — similarities between the Al-Tounsi case and Boumediene v. Bush. Boumediene was a rather complex case involving a whole host of knotty constitutional and statutory issues. What led you to decide to write a novel based on it?

Generative AI Facts And Fallacies

Four insights and misunderstandings to help demystify GenAI for legal professionals.

AP: I was (and remain) particularly interested in the political and legal issues raised by the Guantanamo Bay cases, especially Boumediene. What piqued my interest as a novelist, though, was habeas corpus. It’s such a theatrical and dramatic concept — that a judge can overrule an executive, and order a prisoner’s “body” to come before the bench. For me, the legal questions of how and when the Great Writ would be used in Guantanamo raised all sorts of larger questions about power in general, about our identities, our rights as individual people (citizens or not), and about our responsibilities for each other. The more I read about that particular case, the more I saw an opportunity to address philosophical, psychological and moral issues while simultaneously addressing contemporary political ones.

DL: Al-Tounsi is beautifully written, and it’s also, as I noted earlier, very thoroughly researched. How long did it take you to write?

AP: I started working on it in 2008. I quickly realized that I would have to do an extraordinary amount of research to understand enough law to pretend to be a Supreme Court justice. So I wrote other things while I read all those books and briefs and opinions. That took me years — three or four, I don’t even remember. I had a great guide, though. My friend David Sandomierski, who clerked for a Canadian Supreme Court justice, is a brilliant teacher and very generous with his time. During all those years I asked him a million questions. He directed my reading, and explained concepts and legal traditions that I would have likely learned in law school.

My writing overlapped more and more with the reading. When I finally knew enough to get by, I spent a couple more years working mostly on the characters, story, and craft. So it has been a very long road, indeed.

Anton Piatigorsky (by Greg Pacek)

DL: As our culture critic Harry Graff noted in his review, a number of the characters bear resemblances to actual justices of the Court (and others do not). What’s so great about your characters is how richly drawn they are, and how the reader can sense the humanity behind the powerful and prestigious posts they hold. Can you share a little bit about your process for creating characters, and how you decided to merge fiction and reality?

AP: I wanted the novel to be both a compelling story of justices’ lives and a meaningful commentary on the law. I quickly realized that I had to use aspects of the real jurisprudence to do that. Since I’m a firm believer in legal realism, that also meant using some aspects of the actual justices’ personal histories. I just don’t think methodology can be separated from life experience. A judge who denies that connection might have a brilliant comprehension of law, but I doubt they have a very subtle and nuanced understanding of human behaviour. Who we are — and why we are that way — pervades everything we think and do and say. A life in playwrighting and fiction quickly taught me that.

That said, all my characters remain entirely fictional, even when they resemble real people. I took endless liberties with them; they are not meant to be the same people that we know. That’s one great thing about fiction: if you borrow some aspects of real people while inventing others, it creates something new.

I am most interested in characters who are the best possible versions of themselves. It’s more interesting and fun. It makes readers root for them, rather than roll their eyes at their stupidity. I love and respect these characters. I always make them try hard to be good and fair and just, even when they display personal contradictions and conflicts. Like the real justices of the Supreme Court, these characters have enormous professional integrity and intelligence, intertwined with complex and thorny inner lives.

DL: Many of our readers are lawyers who aspire to (non-legal) writing careers. As a professional writer, what advice would you offer them about how to leave the legal world for the literary?

Expect a pay cut!

Other than that, lawyers have a fantastic head start. They are already full-time writers, and they actually know something meaningful about the world. They have access to real stories, and — more importantly — knowledge of how certain kinds of stories happen. They understand the process of legal action, the procedure, the reasons, and the results. That’s enormously valuable.

But you have to be “irresponsible” with what you know. As professionals, lawyers have a great incentive (and duty) to be responsible at all times. In contrast, when creating a world or a story, you have to let your mind behave in more random ways, making odd and unexpected associations, running with those associations, and generally taking risks you would never make in real life. The first concrete thought I had writing Al-Tounsi was: what if some justice’s dying cat sparks his emotional crisis about Guantanamo Bay? It’s absurd. But I followed through with it, and ended up with this novel.

DL: And what a novel it is. Congratulations, and thanks for taking the time to chat!

(Disclosure: I received a review copy of this book)

Al-Tounsi [Amazon (affiliate link)]

Earlier: Standard Of Review: In ‘Al-Tounsi,’ A Non-Lawyer Analyzes The Supreme Court

David Lat is the founder and managing editor of Above the Law and the author of Supreme Ambitions: A Novel. He previously worked as a federal prosecutor in Newark, New Jersey; a litigation associate at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz; and a law clerk to Judge Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. You can connect with David on Twitter (@DavidLat), LinkedIn, and Facebook, and you can reach him by email at [email protected].

David Lat is the founder and managing editor of Above the Law and the author of Supreme Ambitions: A Novel. He previously worked as a federal prosecutor in Newark, New Jersey; a litigation associate at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz; and a law clerk to Judge Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. You can connect with David on Twitter (@DavidLat), LinkedIn, and Facebook, and you can reach him by email at [email protected].