Have you ever heard of the Dunning-Kruger effect? I hadn’t, and I am perfectly willing to acknowledge my ignorance, unlike some who think they know everything and it’s when they open their mouths that you realize that’s not true. We all know people (not just lawyers) like that. (Let’s stipulate that it’s hard for lawyers to do that, not to open their mouths, but to admit ignorance.)

Have you ever heard of the Dunning-Kruger effect? I hadn’t, and I am perfectly willing to acknowledge my ignorance, unlike some who think they know everything and it’s when they open their mouths that you realize that’s not true. We all know people (not just lawyers) like that. (Let’s stipulate that it’s hard for lawyers to do that, not to open their mouths, but to admit ignorance.)

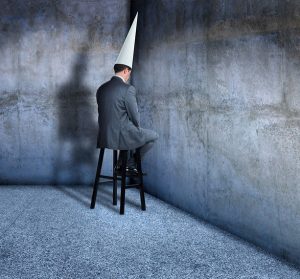

The Dunning-Kruger effect posits that while people think they are highly competent, it’s just the reverse. In other words, we are clueless about our own incompetency. It’s a form of cognitive bias, so that we are unable to recognize our own incompetency.

We overpromise and underdeliver. How does that happen? We’re not told when we underperform. Feedback is essential to an accurate assessment of our abilities or lack thereof. As I noted in last week’s ATL column, yearly performance evaluations don’t cut it. Annual performance evaluations contain stale information, and so the employee is left to head scratch about what it was that dinged his evaluation. We all want to think we are better than average, stars in fact, but the harsh, cold truth is that we aren’t — far from it.

7 Key Trends In Law Firm Rate Negotiations

And how to navigate them in 2026.

So, paraphrasing Confucius, the hard task is to know what we don’t know. Scary news for us lawyers who can be disciplined for the failure to be competent in whatever area(s) we represent clients. And it’s not just the substantive law in which lawyers need to be competent. We need to be tech-savvy as well or retain someone who is, given that so much is now driven by technology.

Comment 8 to the ABA Model Rule 1.1 discusses the need for lawyers to “… keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology….” Is the Dunning-Kruger effect at play here when it comes to lawyer competency about technology? You tell me, but my sense is that it is.

Being tech savvy, especially in litigation, is critical, and I would bet that some, if not many, dinosaurial small and solo firms are way behind the curve on this point. Do they know enough to know that they don’t know enough? It’s especially hard to turn over discovery and other tasks to vendors who know how to do these chores (and that’s what they are) when there’s a corresponding lack of fee-generating income to the firm.

We don’t know what we don’t know. Remember then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld pointing that out some years back? We snickered then, but maybe we shouldn’t have.

How LexisNexis State Net Uses Gen AI To Tame Gov’t Data

Its new features transform how you can track and analyze the more than 200,000 bills, regulations, and other measures set to be introduced this year.

And because we don’t know, we don’t know how to correct our ignorance unless someone points it out to us. However, there’s the problem: few people, if any, respond well to criticism. Defensiveness rears its ugly head and we become even more entrenched in our ignorance, so we can’t even recognize the limits of our knowledge.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is at play in our profession all the time. (Google the term if you don’t want to take my word for it.) It’s not about intelligence, but rather about how we don’t understand the limits of what we know.

So, for example, an attorney might be very confident about predicting a win at trial, but the trier of fact snatches defeat from the jaws of victory. Of course, that’s never happened to you.

We all think that we are smarter and more skillful than we actually are. Ignorance drives confidence. And that confidence, that being misinformed or just downright wrong, can drive you right into a ditch. So, what if you don’t know what you don’t know? Overconfidence can lead to ditches such as malpractice and discipline. Sure buzzkills.

Former ATL columnist Keith Lee wrote about the Dunning-Kruger effect several years back. What he cautioned against then is still, if not more, operative today.

More evidence of the Dunning-Kruger effect on our profession? Read Bryan Garner’s article on “Why Lawyers Can’t Write.” He attributes, in part, our lousy writing skills (no comments here, please, snide or otherwise) to that effect. He opines that we have a “pervasive” Dunning-Kruger problem. How does that manifest itself in our writing? How about use of the passive, instead of the active voice as just one example? If you have a copy of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, then you should know how to write well. And if you aren’t familiar with the thin volume of the best writing advice ever, then shame on you. Get thee to Amazon forthwith.

Baby lawyers: listen up. Garner says that the Dunning-Kruger effect on legal writing is much more prevalent among newer lawyers than experienced practitioners and he says that litigators tend to be better writers than transactional lawyers. No surprises there.

How many motions and trial and appellate briefs do transactional lawyers write? Not many, I guess, and if they do, should I say that that would be the Dunning-Kruger principle at work? Garner says that “the unskilled don’t know that they’re unskilled.” So, when you want to sign up a client or retain a client and the subject matter is unfamiliar to you, refer to Comment 8 to ABA Model Rule 1.1.

Our livelihoods depend upon our expertise in one field or another or maybe more, so I am always amused, or should I say bemused, about attorneys who say they can do it all, never lost a case (er, perhaps because they’ve never tried one?) and act like they are masters of the legal universe. Not.

We are nowhere near as smart as we think we are, we can’t write for beans, we can’t successfully predict how our case will turn out, and so on. All that we think we are we are not, and maybe that’s a good thing for both the profession and us individually. As for that slice of humble pie I need to eat, make mine coconut cream, please.

Jill Switzer has been an active member of the State Bar of California for 40+ years. She remembers practicing law in a kinder, gentler time. She’s had a diverse legal career, including stints as a deputy district attorney, a solo practice, and several senior in-house gigs. She now mediates full-time, which gives her the opportunity to see dinosaurs, millennials, and those in-between interact — it’s not always civil. You can reach her by email at [email protected].

Jill Switzer has been an active member of the State Bar of California for 40+ years. She remembers practicing law in a kinder, gentler time. She’s had a diverse legal career, including stints as a deputy district attorney, a solo practice, and several senior in-house gigs. She now mediates full-time, which gives her the opportunity to see dinosaurs, millennials, and those in-between interact — it’s not always civil. You can reach her by email at [email protected].