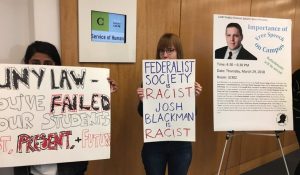

Should this be allowed on law school campuses? (Via Josh Blackman)

Two weeks ago, I had the pleasure at the University of Illinois of moderating and participating in a “Free Speech Principles on College Campuses” event featuring two noted constitutional commentators/academic administrators, Geof Stone of the University of Chicago and Erwin Chemerinsky of UC Berkeley. Both are influential First Amendment thinkers, and both have also served as deans of major law schools (and Geof as a provost as well).

I found their discussion to be among the most substantive and sophisticated I have heard over the past several years on this important topic. Erwin and Geof began by laying out many areas of agreement among courts and scholars who have looked at free speech flare-ups on public university campuses over the past several decades. For example, they discussed the unfortunate but unavoidable reality that hateful speech does not lose its constitutional protection because of its odious motivations, and that as a result so-called “hate speech” codes are almost inevitably going to be unconstitutional. (For purposes of the discussion, the participants really didn’t draw many distinctions between public and private universities, since most prominent private universities try to hold themselves to the same First Amendment standards that bind public institutions.) Erwin and Geof also explained why people who protest against unpopular speakers by trying to shout the speakers down or otherwise obstruct the speakers’ events can (and ordinarily should) be subject to discipline. On the other hand, both Erwin and Geof were very clear to highlight the ways in which university authorities can and should protect individuals from true threats, harassment (which has a legal definition focused on how targeted and persistent a particular course of offensive expressive conduct is), and defamation.

The three of us then mused about why many (most?) college students today seem not to embrace the basic notion that conservative speech they find to be stigmatic, offensive, unsettling, and even infuriating must nonetheless be permitted to be uttered and heard on college campuses, so long as it doesn’t cross the line into threats, harassment, or defamation. The explanations ranged from (at the less-heartening end of the spectrum) the failure of modern college students to appreciate that if majorities are allowed to silence minorities, then throughout American history righteous groups like the abolitionists, civil rights protestors, women’s rights advocates, and others would not have been able speak and convince people of the justness of their causes, to (more upliftingly) a deep sense of empathy among young adults today that allows a wider swath of students to feel the pain suffered by individuals who are part of racial, religious, or gender minority groups who are often the explicit or perceived targets of some of the speakers causing dustups at campuses around the country.

Two important topics we discussed don’t get enough attention but are particularly challenging. One is the appropriateness/wisdom of university administrators speaking out — on behalf of their institutions — to criticize hateful speech that must be tolerated but that need not be embraced. Erwin felt it was a dean’s job to publicly condemn prominent expressions of bigotry and intolerance that take place within the law school community, even though those expressions in many cases might be constitutionally protected (and thus immune from punishment). For Erwin, the biggest factor in deciding whether to speak out, in his capacity as a dean, against such expressions of racism, sexism, religious hostility, etc. is simply his desire not to talk so frequently that people stop listening to him. But putting aside his strategic concern over picking his spots, Erwin saw no philosophical problem with the university weighing in on one side of such public policy debates.

Geof, by contrast, articulated and defended a much narrower conception of the university as speaker, one to which the University of Chicago tries to adhere. According to this stance, the university does not weigh in on contested public policy matters that themselves do not involve the core of the university’s academic operations; people have understandably strong opinions about many hot topics, but the university’s role is to ensure that individuals get to air those opinions, not to shape or influence these opinions via university imprimaturs or condemnations. Indeed, for Geof, the very reasons that we allow and encourage a broad range of speakers on college campuses in the first place — our desire to facilitate a robust marketplace of ideas and encourage people to learn how to process information and arguments and come to their own conclusions — argue strongly in favor of the university keeping its own institutional mouth shut. Yet for Erwin, the key line is between regulation and condemnation; as long as speakers remain free (in the regulatory sense) to utter their controversial messages, they need not be immune from whatever persuasive influence the university itself might exert on the community audience.

Another particularly vexing topic is the question of when the costs of providing security for controversial speaker events justifies the cancellation or termination of the event. Supreme Court and lower court case law is extremely underdeveloped here — leading Erwin to suggest we don’t really know what the rules are going to be. The Supreme Court has suggested that it would be impermissible to require a speaker to pay for security costs that arise because opponents to the speaker might show up and cause trouble; that would confer a “heckler’s veto” that is inconsistent with the First Amendment’s core idea that unpopular speakers should not be silenced simply because they are (for the moment) in the minority.

Why Better Billing Statements Can Improve Your Firm’s Finances—And Your Client Relationships

Outdated billing is costing law firms money. Discover how clear, modern billing practices boost profits, trust, and cash flow in 2025.

The Court’s sentiments are quite understandable and indeed laudable, but I’m not sure how absolutely we can apply them, especially to modern university settings, where security costs for some events runs into the several millions of dollars. In this regard, it bears noting that universities don’t have robust revenue-generating capacities the way cities and counties do, and universities’ primary mission, of course, involves the classrooms and laboratories more than it does massive rallies and demonstrations (even if the latter be a significant extracurricular component of the educational experience.)

I think that invitations to individuals to speak in classrooms and other nonpublic parts of campus — invitations that a university didn’t have to extend in the first place — should be rescindable on account of anticipated cost. But the question is harder when outside groups seek to use traditional or designated public forum parts of public university campuses (like a main lawn or the area outside the administration building) for events that raise legitimate security concerns. Geof offered his quite sensible view that if things at a particular rally or speech are truly getting out of hand and public safety is being compromised, university officials can shut down the event. But if that is so, then why can’t they block an event before the fact, when they can produce clear (non-speculative) evidence to suggest violence is likely to ensue (even if spending more security money up front could have deterred the violence in both cases)?

For those interested in watching/hearing the Stone/Chemerinsky discussion I moderated, here’s a link:

Vikram Amar is the Dean of the University of Illinois College of Law, where he also serves the Iwan Foundation Professor of Law. His primary fields of teaching and study are constitutional law, federal courts, and civil and criminal procedure. A fuller bio and CV can be found at https://www.law.illinois.edu/faculty/profile/VikramAmar, and he can be reached at [email protected].

Vikram Amar is the Dean of the University of Illinois College of Law, where he also serves the Iwan Foundation Professor of Law. His primary fields of teaching and study are constitutional law, federal courts, and civil and criminal procedure. A fuller bio and CV can be found at https://www.law.illinois.edu/faculty/profile/VikramAmar, and he can be reached at [email protected].