(Photo via Yale Law School)

In case you missed the news amidst the (justifiably) breathless coverage of the latest associate pay raise (#NYto190), here at Above the Law we recently released our 2018 law school rankings. And there’s a new number one: congratulations to the University of Chicago Law School!

For those who follow legal education closely, the ascendancy of Chicago Law should come as no surprise. For years, Chicago has had a colorable claim to being the nation’s best law school in at least two critical respects: the quality of the legal education it provides, and the value it adds to its students as they go from being 1Ls to practicing lawyers. Chicago’s success on that second measure, reflected in the great jobs obtained by its graduates, explains its success in the ATL law school rankings, which focus on outcomes like alumni employment, satisfaction, and debt loads (as opposed to, say, the number of volumes in the library).

Decrypting Crypto, Digital Assets, And Web3

"Decrypting Crypto" is a go-to guide for understanding the technology and tools underlying Web3 and issues raised in the context of specific legal practice areas.

Yes, Chicago Law has had its share of controversy in recent months.[1] But don’t let the circus distract from the substance: Chicago might very well be the nation’s best law school. [2]

Wait, you say — what about Yale Law School? Hasn’t YLS been the number-one law school in the U.S. News law school rankings since their inception?

As a loyal and enthusiastic Yale Law alum, I firmly believe it is a great and wonderful institution. I’m grateful to YLS for the education I received, the mentors I gained, and the friends I made while there. I give Yale Law much of the credit for my quirky, interesting career as a lawyer turned legal blogger. When people admitted to YLS ask me whether they should matriculate, I often tell them yes (after having a conversation with them about who they are and what they want out of law school, of course; picking a law school requires consideration of more than just a U.S. News ranking).

But my love for Yale Law School also includes a love for the values it represents, such as truth (“Lux et veritas”) — and the truth is that Yale Law might not be the “best” law school. Or at least not to the degree that its decades-long dominance of the U.S. News rankings might suggest.

Paying for Law School in 2025: A Straight-Talk Playbook

Juno has consistently secured the best private loan deals for students at the Top MBA programs since 2018—now they’re bringing that same offer to law students, at no cost. Students can check their personalized offers at juno.us/atl This article is for general information only and is not personal financial advice.

For starters, is Yale Law truly a “law school”? The school takes a highly theoretical, interdisciplinary approach to legal education that arguably takes the “law” out of “law school” (at least if we construe “law” as black-letter legal doctrine). Yale Law is a great something — writer and YLS alum Elizabeth Wurtzel describes it as “a cult of the Fourteenth Amendment… that happens to have a registrar’s office” — but that something might not be a law school (at least if we view law school narrowly, as a place that teaches students legal doctrine so they can practice law).[3]

Kidding aside, I think Yale’s standing in the law school hierarchy is better reflected in the ATL rankings than the U.S. News rankings. The ATL rankings suggest that Yale Law School, while one of the nation’s best law schools, is not the undisputed best law school of all time, as U.S. News might lead you to believe. Here’s how Yale has fared in the six years of ATL law school rankings:

Credit where credit is due: Yale is the only law school that has ever been number one more than once, and it has been the top law school for three out of six years. So it’s certainly a great law school. But it shares that distinction with several other institutions, including Harvard, Stanford, and Chicago, and having to pick between them and Yale is a real choice, not a no-brainer.

Let’s dig a little deeper. Why is Yale not number one in the 2018 ATL rankings?

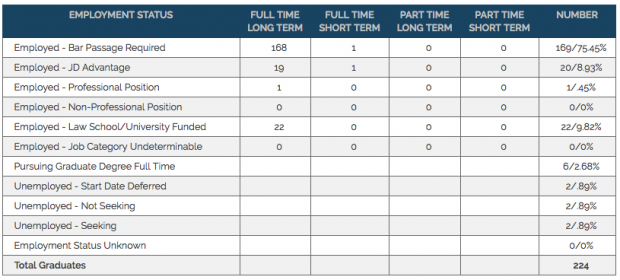

The 2018 rankings are based in large part on job outcomes for the law school classes of 2017. Here are the employment statistics for the YLS class of 2017:

For the average law school, putting three-quarters of graduates in full-time, long-term, bar-passage-required jobs is totally respectable. But as ATL research director Brian Dalton pointed out to me, when you compare Yale to its peers, 75 percent is well below the average employment score for the top 10 schools (88 percent).

Where did the rest of those Yale grads go? Nine percent wound up in “JD Advantage” jobs, and 10 percent took school- or university-funded positions.

First, let’s look at JD Advantage jobs, defined as jobs “for which bar passage is not required but for which a JD degree provides a distinct advantage.” In our rankings, we give zero credit for JD Advantage jobs, which are often B.S. in the eye of the beholder. If you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail; if you’re a law school with lots of underemployed grads working in low-paid jobs outside the legal field, everything looks like a JD Advantage job.

But we readily admit that there are truly desirable jobs out there that are JD Advantage jobs. And they are the positions typically taken by Yale grads, who easily could have gotten offers at Cravath but decided instead to launch startups, make documentary films, or establish charter schools. So giving YLS no credit for JD Advantage jobs might be unfair, since Yalies are in fact becoming McKinsey consultants, foundation executives, and bestselling authors (as opposed to Starbucks baristas with a JD-Advantageous understanding of tort law as applied to hot coffee).

Second, let’s turn to the school-funded positions. In our rankings, we give zero credit for such posts, which historically were abused by lower-ranked schools to make their awful job numbers look better. In the past, before various reforms to how the ABA tracks employment outcomes, schools would do things like hire a slew of unemployed graduates to do administrative work at the law school for a few weeks right around the time that job surveys went out.

Not counting school-funded jobs makes sense for the world of law schools writ large, but it might not map well onto Yale Law School. Why? Yale awards a number of highly coveted public-interest fellowships that allow graduates to work on such issues as immigration reform, environmental protection, and disability rights, for a full year, fully — and decently — paid. Public-spirited YLS grads go into these fellowships even though they easily could have trooped off to Skadden.

Speaking of Skadden, not counting school-funded public interest fellowships arguably gives rise to disparate treatment of substantially similar positions. Skadden sponsors its prestigious Skadden Fellowships to support public interest work, and if a Yalie gets one of those positions, it fully counts as a real legal job. But if a Yale grad takes a Yale fellowship to do pretty much the exact same work, at the exact same organization, it counts as a big zero. That might make YLS’s employment outcomes look worse than they really should.

What’s the bottom line of this rambling analysis? First, Yale Law School is a great law school, as reflected in its cumulative performance in the ATL law school rankings (even if it’s not head and shoulders above all others, as the U.S. News rankings might suggest).

Second, Yale’s relatively weak performance in the most recent ATL rankings — number five, which is still excellent, just not number one — can be understood once you look at the underlying numbers. Yale suffers because of methodological decisions we’ve made to root out certain abuses, even though Yale doesn’t engage in any of the abuses in question. (Pick your favorite saying here — a few bad apples spoil the bunch, this is why we can’t have nice things, etc.)

Third, the case of Yale shows how data, while true or accurate in one sense, can be misleading in another. Yale’s job outcomes look worse than those of its peers, but that’s mainly because Yalies are blessed with either (1) the ability to take the road less traveled and try a non-conventional career right after graduation, knowing that they can always return to the traditional legal world if they like, or (2) the chance to do great public interest work, with generous financial support from their alma mater.

Rankings are like any tool: they can be used wisely, or they can be used poorly. Use the ATL rankings wisely, and don’t be afraid to dive below the surface — because numbers don’t always tell the whole story.

[1] Yes, I’m talking about the Edmund Burke Society controversy. As the resident (mildly) right-of-center editor here at Above the Law, I received a number of complaints from conservative friends with Chicago Law ties about ATL’s harsh coverage of the Society. I certainly understand and appreciate the objections, but I would like to use this opportunity to remind people that I stepped down as managing editor of ATL last year. I am now responsible only for what appears under my personal byline. Thank you.

[2] For many years, Harvard Law School had the strongest claim on being the nation’s best law school. But HLS hasn’t been the same since it went all soft and dispensed with the rigor of a conventional letter-grading system in favor of a Yale-style, Honors/Pass grading system. That move might have increased HLS student happiness and reduced student stress, but at the expense of the brutal, Hunger-Games-style competition that made Harvard Law the badass place it once was. (Know your brand, HLS! Just because something works for Stanford and Yale doesn’t make it right for you.)

[3] Criticism of Yale as excessively theoretical is not entirely fair. First, Yale has one of the best clinical programs in the country, giving students amazing opportunities to get practical legal training (I conducted my first trial as a 2L). Second, I know that Yale’s new dean, the remarkable Heather Gerken, has deep respect for the world of legal practice and plans to enhance and expand the opportunities for YLS students to learn about legal practice as well as theory.

Earlier: The 2018 Law School Rankings Are Here, With Major Employment-Driven Changes At The Top

David Lat is editor at large and founding editor of Above the Law, as well as the author of Supreme Ambitions: A Novel. He previously worked as a federal prosecutor in Newark, New Jersey; a litigation associate at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz; and a law clerk to Judge Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. You can connect with David on Twitter (@DavidLat), LinkedIn, and Facebook, and you can reach him by email at [email protected].

David Lat is editor at large and founding editor of Above the Law, as well as the author of Supreme Ambitions: A Novel. He previously worked as a federal prosecutor in Newark, New Jersey; a litigation associate at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz; and a law clerk to Judge Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. You can connect with David on Twitter (@DavidLat), LinkedIn, and Facebook, and you can reach him by email at [email protected].