Now that Senator Manchin declared he will vote to confirm Judge Jackson to the Supreme Court, Jackson’s confirmation in a week or so is all but a foregone conclusion.

Now that Senator Manchin declared he will vote to confirm Judge Jackson to the Supreme Court, Jackson’s confirmation in a week or so is all but a foregone conclusion.

Will Jackson usher in a new era of judging on the Court? This outcome is very unlikely.

The Court now has six conservative, Republican-nominated justices and three liberal, Democratic-nominated justices, and Justice Breyer is one of the liberals. Filling his position with another Democratic-appointed liberal is not likely to shift the ideological center of the Court in either direction. If anything, we might expect Judge Jackson to be more moderate than Breyer, at least as she acclimates to life on the Court.

For one thing, justices tend to be more ideologically moderate at the start of their tenure on the Supreme Court than later in their tenure. Buffering this point, David Savage and Nolan McCaskill wrote for the Los Angeles Times that the confirmation hearings reaffirmed suppositions that “[Judge Jackson’s] words suggested she would be a moderate liberal on the high court, more like Breyer than Justice Sonia Sotomayor, and more inclined to work with her colleagues than to denounce them in fierce dissents.”

This trajectory of justices’ historic movement from moderate ideologies once confirmed to more radical ideologies once they sit on the Court is theoretically and empirically supported. Justices might not want to rock the boat and shake things up right after joining the Court. Instead, they may be more comfortable agreeing with other justices and acclimating to their roles.

This may be accompanied by fewer separate opinions to start and more as they have additional terms under their belts. Justices in their first years tend to be assigned less contentious majority opinions as well (Gorsuch was an exception authoring five 5-4 decisions in his first term on the Court).

This shift to more polarized ideology positions is all supported by data. We can see this from examples of other justices over the course of their times on the Court. The example below shows how Justices Thomas, Breyer, Alito, and Sotomayor voted more ideologically as they passed through more terms on the Court.

This graph and the other ideological measures used in this article are based on numbers established by Martin-Quinn (MQ) Scores which track justices’ voting patterns with other justices to determine where they are ideologically situated. Negative MQ scores highlight more liberal votes while positive MQ scores indicate more conservative votes.

Each of the justices above became more ideological the longer they sat on the Court. Thomas, who was always a likely conservative vote, began in his first term with an MQ score of 2.74. By year seven Thomas’ score rose to 3.8. Alito’s ideology also increased. His score moved from 1.43 in his first term on the Court to a score of 2.16 in his most recent term on the Court. Conversely, Justice Breyer moved from a -0.33 score in his first term on the Court to -1.90 in his most recent term. Sotomayor’s MQ score was -1.61 in her first term on the Court and -3.96 in her most recent term. These examples show increased ideological voting across both liberals and conservatives as the justices sit for more years on the Court.

This appearance of moderation prior to ideologic voting is consistent with the design of the federal judiciary with lifetime tenure. As justices acclimate to the role of judging at the apex of the American court system and without the binding nature of precedent, it is entirely plausible that they begin to strive to develop their own modes of judicial interpretation. This in turn plays out in the external display of greater ideological preferences over time.

Sometimes as was the case with Justices Scalia, Ginsburg, and Rehnquist, justices pass away during a Supreme Court term and so a replacement is immediately necessary. When Justices retire they can strategically plan to leave the Court at their discretion, when they feel a president will nominate a likeminded successor.

This is even more pronounced with Justice Kennedy and Breyer’s retirements where the justices were and will be replaced by their former clerks (Kavanaugh and Jackson respectively). On the other hand, as was the case with Justice Ginsburg, when justices do not heed the call to strategically retire, the door remains open to a large ideological shift if the justice dies while still a member of the Court. Even planned retirements have their hazards though. To get our heads around what to expect when Breyer retires and when Jackson takes his seat, below are several examples from the Court’s modern history.

Justice Marshall

Justice Marshall’s retirement is a unique example within this dataset. While Marshall retired due to health concerns during President George H.W. Bush’s presidency, he didn’t plan for things to work out that way. Instead, he wanted his position filled by a likeminded successor. Unfortunately, Marshall did not foresee the extent of his health declining when it did and so he had to step down. He passed away right before President Clinton took office in 1993. President Bush nominated Justice Thomas as Marshall’s successor leading to one of the greatest historic ideological shifts in a Supreme Court seat.

This ideological shift looks as follows:

As you can see, Marshall was far and away the most liberal justice on the Court during the 1990 term and Justice Thomas is the most conservative justice on the Court in his first term in 1991.

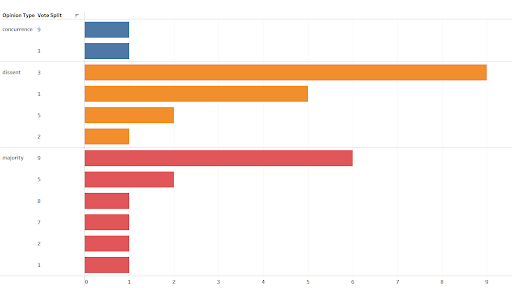

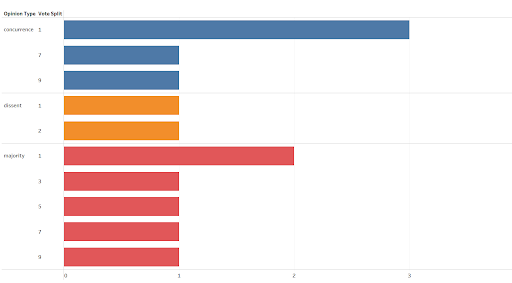

We learn some important information about justices’ final terms through their judicial behavior. In his last year on the Court Justice Marshall authored 31 opinions of which two were concurrences, 17 were dissents, and 12 were majority opinions.

Of the 31 opinions Marshall authored, seven were in 5-4 votes (shown above as 1 for Vote Splits or the difference between votes in the majority and in dissent). As Justice Marshall was already in the Court’s liberal minority, he was hard pressed to move the Court’s ideological pendulum leftwards. Of the seven opinions Marshall authored in 5-4 decisions, his only majority opinion was in Burns v. United States — a case looking at the requirements for upwards departures from U.S. Sentencing Guidelines ranges. In that case, Marshall was joined by liberal colleagues Justices Stevens and Blackmun, and more conservative colleagues Justices Scalia and Kennedy.

Across the seven 5-4 decisions where Marshall authored an opinion, all were joined by Justice Blackmun and six of the seven were joined by Justice Stevens (Stevens was only on the opposite side of Peretz v. United States). Contrastingly, Justices Souter and O’Connor were on the opposite side from Justice Marshall in all seven decisions.

Justice Thomas

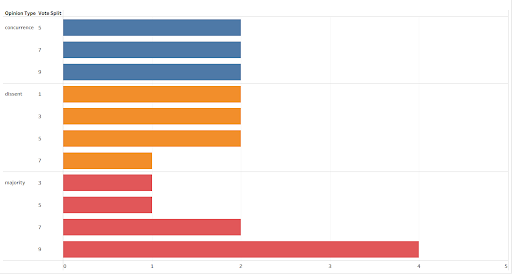

Justice Thomas is arguably the most conservative justice on the current Supreme Court. While he started his career on the Court with a strong rightward thrust, as the first graph shows, this only grew over time. Thomas authored 21 opinions in his first term on the Court.

Of Thomas’ opinions, six were concurrences, seven were dissents, and eight were majority opinions. None of the concurrences or majority opinions were written in 5-4 decisions. Justice Thomas authored dissents, however, in two 5-4 decisions. These came in the cases Doggett v. United States and Foucha v. Louisiana. Doggett dealt with the timing of prosecution for certain crimes, while Foucha dealt with the requirements for holding a defendant committed to a psychiatric hospital after an insanity plea. Justices Scalia and Rehnquist were the only two justices to join both of these dissents.

Justice Breyer

President Clinton nominated Justice Breyer in 1994 to replace Justice Blackmun. Both justices were liberal and so the switch did not create a great ideological shift on the Court. Still Justice Breyer began on the Court as much more of a moderate than the more liberal Justice Blackmun.

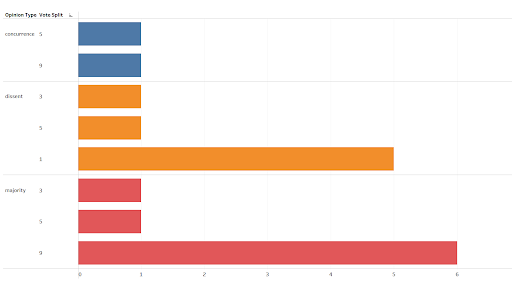

Justice Breyer authored 17 opinions during his first term on the Court and five of these opinions were authored in cases with 5-4 votes.

All five of Justice Breyer’s opinions in cases that came down to the difference of a single vote were in dissent. The category Justice Breyer authored the most opinions in was 9-0 majority opinions of which he authored six.

Justices Stevens and Souter joined four of the five dissents Justice Breyer’s authored in 5-4 decisions. The one case where Steven and Souter did not also dissent was in Tome v. United States. Justices Scalia and Kennedy were on the opposite side of Justice Breyer in all 5-4 decisions where he authored dissents.

Justice Alito

Fast forward just over a decade and we have Justice Alito replacing Justice O’Connor. Since Justice O’Connor retired in the middle of the 2005 term, Justice Alito sat on the Court for the second half of that term. His first full term on the Court was in 2006.

Justice O’Connor moved in the liberal direction during her tenure on the Court so that by the time she retired she was the median justice on the Court. The Court took another sharp turn to the right when O’Connor was replaced by the more conservative Justice Alito.

Alito’s confirmation moved the Court from a somewhat ideologically balanced Court into one that clearly had a conservative tilt. Alito authored 15 decisions during his first full Term on the Court in 2006. Of these 15 decisions, eight were in 5-4 vote splits and four of those eight were majority opinions.

The new conservative bloc played a key role in the 5-4 votes in cases where Justice Alito authored an opinion. The four more conservative justices — Alito, Roberts, Thomas, and Scalia — agreed in seven of the eight instances where Justice Alito authored an opinion in 5-4 decisions. Kennedy was on the same side as Alito in five of those seven instances while Roberts aligned with Alito in all eight instances. On the other end of the spectrum, Justices Ginsburg and Stevens voted in the opposite direction in all eight 5-4 decisions where Justice Alito authored an opinion.

Justice Kennedy

After a heap of speculation about whether he would step down, Justice Kennedy officially retired from the Court at the end of the 2017 term. While Justice Kennedy had long been dubbed the Court’s swing vote, he didn’t embody this moniker during his final term on the court. Instead, his positions during the 2017 term were overwhelmingly conservative.

His ideological position on the Court was still in the Court’s center in his final term on the Court.

Upon Kennedy’s retirement, Justice Roberts took the helm in the Court’s center, making this middle more conservative than it had been in the past. Kennedy’s replacement, Justice Kavanaugh was more conservative than Kennedy in his first term on the Court and this created a stronger conservative bloc than existed during Kennedy’s final years on the Court.

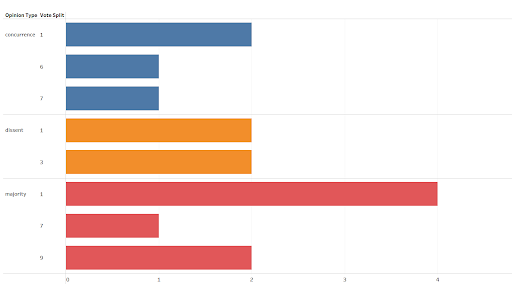

Justice Kennedy authored 13 opinions during the 2017 term. These broke down into five concurrences, two dissents, and six majority opinions.

Of these 13 opinions, six were in 5-4 decisions. We can gauge the conservative nature of Justice Kennedy’s votes and opinions by the justices that aligned with him in these 5-4 decisions. The more conservative justices – Gorsuch, Alito, and Thomas agreed with Justice Kennedy in all six of these decisions while Justice Breyer, Sotomayor and Kagan opposed Justice Kennedy’s position in each of these cases. The only case that shifted the balance a bit was South Dakota v. Wayfair.

In Wayfair, Justice Roberts sided against Justice Kennedy while Justice Ginsburg was on the same side as Justice Kennedy. Justice Roberts aligned with Justice Kennedy in the other five 5-4 decisions where Kennedy authored an opinion and Justice Ginsburg opposed Justice Kennedy’s positions in those same five cases.

Justice Breyer’s Retirement and What to Expect From Judge Jackson

The last full term of data on Justice Breyer is from the 2020 Supreme Court Term. Justice Breyer was one of the three liberal justices on the Court compared to the six steadfast conservative justices on the current Court. Justice Breyer now sits ideologically in between Justices Kagan and Sotomayor.

Justice Jackson’s confirmation cannot shift the Court’s ideological balance unless she turns out to be more conservative than expected, or one of the conservative justices suddenly shifts towards the liberal direction. Neither outcome is likely. Based on the history of nominations looked at in this article, we might expect to see Jackson as more of a moderate in her first term on the Court, possibly swapping positions with Justice Kagan as the most moderate liberal on the Court.

While Justice Breyer’s retirement is strategic in the sense that this stymies potential efforts to make the Court even more conservative, this retirement does little to shake up the balance of the Court. The only way we are likely to see a major shift in the overall justices’ preferences in the short run is if one of the more conservative justices leaves the Court under President Biden, and Biden has an opportunity to nominate a justice to succeed in their place.

Read more at Empirical SCOTUS…

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. For more information write Adam at [email protected]. Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.