(Image via Getty)

How do you do what you do?

For attorneys, the answer is usually “money and a flexible moral code.” But that’s the answer to the different question, “how do you do what you do and sleep at night?” But to really answer “how do you do what you do?” requires the mind of a programmer. When was the last time you really thought about all the little mental tasks performed in answering a “simple” legal question?

Whenever generative AI finds its way into a legal application, I think about all those little steps.

This afternoon, Thomson Reuters launched a slew of AI-driven features. Or, in the language of the company’s long-term strategy, “skills.” As a rhetorical frame, “skills” really focuses you on thinking about what goes into these features. Building deposition outlines based on the nature of the case and the underlying legal standards in the chosen jurisdiction? Make a timeline based on hundreds of emails? Flag discovery documents with jokes or indicia of fraud? Thomson Reuters AI can do all that. But, thinking back, what tasks did you expect a first-year to perform in whipping up that draft outline or summary? What proficiencies did you expect them to already have when you assigned the task? When TR provides that draft, can you see those unspoken elements in the final product?

With the right vision, AI is an opportunity to interrogate for the first time exactly how we do what we do.

Thomson Reuters is more than just Westlaw, but the crown jewel of the Thomson Reuters legal suite presents as good a jumping off place for this journey of self-discovery as any.

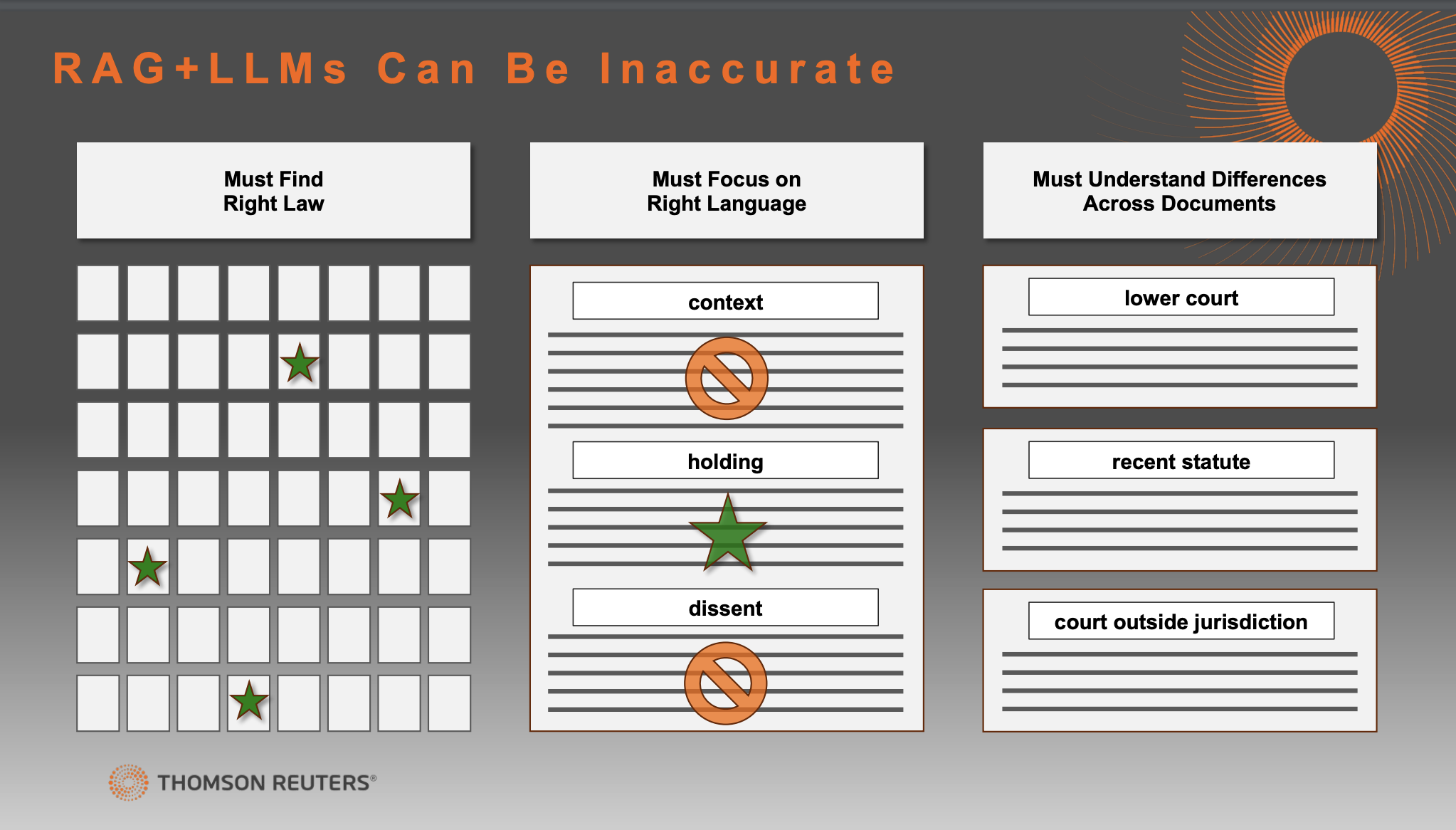

All the smoke surrounding generative AI as a legal research tool focuses on hallucinations. Where the system makes up a bunch of fake cases that get lazy lawyers sanctioned. But Mike Dahn, Head of Westlaw Product Management, explains that solving hallucinations is actually a pretty low bar to clear if you know what you’re doing. Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) is a fancy way of saying the large language model draws on trusted data — in this case, the Thomson Reuters library of materials — and can more or less handle the hallucination risks that crop up with unfiltered AI.

The challenge, Dahn outlines, is in achieving accuracy even when the algorithms stay safely in the realm of reality. Which makes sense, because young lawyers don’t have to invent cases to be wrong.

Even after curing the risk of hallucination, is the system getting tripped up on dissents? Or dicta or straw arguments? Has it figured out the proper import of superseding statutes or regulations? Those are the higher level research skills that attorneys deploy without even realizing, but that a provider has to equip an AI to sort out.

It takes time. From our experience with the product, around 2-4 minutes. Though it’s not fair to compare this to Westlaw’s traditional response time. The proper comparison is to the 2 hours a junior associate would bill for taking all that research and pumping out a two-page memo.

Imagine a client looking to rid itself of an eyesore of a statue. In the AI-assisted research window, the user can pose a simple question — filtered by jurisdiction, of course. While a generic AI might shotgun approach this issue and spit out random — or hallucinatory — thoughts as it tries to please the user with its result, the Westlaw response figures out not just where to look but the key requirements a lawyer needs from the answer.

The “thinking like a lawyer” stuff we don’t consider on a day-to-day basis.

This does overlook issue 7: “is this a Confederate statue that the Supreme Court will invent an exception to in order to appease Harlan Crow?” but nobody’s perfect.

Sarcasm aside, this does get at my overarching quibble with AI-driven research. This technology, appropriately matched with data and expertise, is really good at providing the user with the “right” answer, but what if the right answer isn’t always what the attorney needs. In transactional or compliance work, getting the right answer quickly and reliably is the name of the game.

While it makes for good clickbait, AI isn’t really going to take lawyer jobs. Firms will find a way to use AI’s efficiencies to stretch lawyers thinner and get more work done. But an anonymous Thomson Reuters in-house customer said after seeing these new capabilities: “This is substantially the same advice I just paid to get from outside counsel and was billed about 15 hours.” Law departments always blow smoke about moving more work in house. AI gives them that opportunity whenever the legal problem requires getting the right answer.

But, again, what if the “right answer” isn’t the goal? There’s a reason why most billable hours in litigation aren’t racked up leafing through hornbooks and restatements. When litigators dig into a research question, it’s usually not to find the right answer but to expose — or plausibly create — cracks that a client can slip through. How do we do the sort of research that stretches and distinguishes precedent toward our ends? It’s a higher level thought process that attorneys pick up and never really meditate upon.

That’s the next step in the evolution of AI research. But playing around with the features in this suite of products and remembering that we are only about a year into the commercial viability of this technology, it’s an inevitable one the more we dwell on our own process.

Joe Patrice is a senior editor at Above the Law and co-host of Thinking Like A Lawyer. Feel free to email any tips, questions, or comments. Follow him on Twitter if you’re interested in law, politics, and a healthy dose of college sports news. Joe also serves as a Managing Director at RPN Executive Search.

Joe Patrice is a senior editor at Above the Law and co-host of Thinking Like A Lawyer. Feel free to email any tips, questions, or comments. Follow him on Twitter if you’re interested in law, politics, and a healthy dose of college sports news. Joe also serves as a Managing Director at RPN Executive Search.