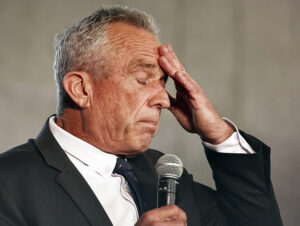

(Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

You may recall that RFK Jr.’s nonsense-peddling anti-vax organization “Children’s Health Defense” (CHD) sued Meta back in 2020 for the apparent crime of fact-checking and limiting the reach of the anti-vax nonsense it posted. Three years ago, the case was tossed out of court (easily) with the court pointing out that Meta is (*gasp*) a private entity that has the right to do all of this under its own free speech rights. The court needed to explain that the First Amendment applies to the government, and Meta is not the government.

Yes, Meta looked to the CDC for guidance on vaccine info, but that did not turn it into a state actor. It was a pretty clear and easy ruling smacking down CHD (represented, in part, by disgraced Yale law professor Jed Rubenfeld). So, of course RFK Jr. and CHD appealed.

Transform Legal Reasoning Into Business-Ready Results With General AI

Protégé™ General AI is fundamentally changing how legal professionals use AI in their everyday practice.

Last week, the Ninth Circuit smacked them down again. And we learn that it’s going to go… very… slowly… to hopefully help RFK Jr. and Rubenfeld understand these things this time:

To begin by stating the obvious, Meta, the owner of Facebook, is a private corporation, not a government agency.

Yes, the majority opinion admits that there are some rare cases where private corporations can be turned into state actors, but this ain’t one of them.

CHD’s state-action theory fails at this threshold step. We begin our analysis by identifying the “specific conduct of which the plaintiff complains.” Wright, 48 F.4th at 1122 (quoting American Mfrs. Mut. Ins. Co. v. Sullivan, 526 U.S. 40, 51 (1999)). CHD challenges Meta’s “policy of censoring” posts conveying what it describes as “accurate information . . . challenging current government orthodoxy on . . . vaccine safety and efficacy.” But “the source of the alleged . . . harm,” Ohno, 723 F.3d at 994, is Meta’s own “policy of censoring,” not any provision of federal law. The closest CHD comes to alleging a federal “rule of conduct” is the CDC’s identification of “vaccine misinformation” and “vaccine hesitancy” as top priorities in 2019. But as we explain in more detail below, those statements fall far short of suggesting any actionable federal “rule” that Meta was required to follow. And CHD does not allege that any specific actions Meta took on its platforms were traceable to those generalized federal concerns about vaccine misinformation.

How Legisway Helps In-House Teams Manage All Legal Matters In One Trusted Place

Operate with AI driven insights, legal intake, unified content and modular scalability to transform efficiency and clarity.

And, even if it could pass that first step, it would also fail at the second step of the test:

CHD’s failure to satisfy the first part of the test is fatal to its state action claim. See Lindke v. Freed, 601 U.S. 187, 198, 201 (2024); but see O’Handley, 62 F.4th at 1157 (noting that our cases “have not been entirely consistent on this point”). Even so, CHD also fails under the second part. As we have explained, the Supreme Court has identified four tests for when a private party “may fairly be said to be a state actor”: (1) the public function test, (2) the joint action test, (3) the state compulsion test, and (4) the nexus test. Lugar, 457 U.S. at 937, 939.

CHD invokes two of those theories of state action as well as a hybrid of the two. First, it argues that Meta and the federal government agreed to a joint course of action that deprived CHD of its constitutional rights. Second, it argues that Meta deprived it of its constitutional rights because government actors pressured Meta into doing so. Third, it argues that the “convergence” of “joint action” and “pressure,” as well as the “immunity” Meta enjoys under 47 U.S.C. § 230, make its allegations that the government used Meta to censor disfavored speech all the more plausible. CHD cannot prevail on any of these theories.

The majority opinion makes clear that CHD never grapples with the basic idea that the reason Meta might have taken action on CHD’s anti-vax nonsense was that it didn’t want kids to die because of anti-vax nonsense. Instead, it assumes without evidence that it must be the government censoring them.

But the facts that CHD alleges do not make that inference plausible in light of the obvious alternative—that the government hoped Meta would cooperate because it has a similar view about the safety and efficacy of vaccines.

Furthermore, the Court cites the recent Murthy decision at the Supreme Court (on a tangentially related issue) and highlighted how Meta frequently pushed back or disagreed with points raised by the government.

In any event, even if we were to consider the documents, they do not make it any more plausible that Meta has taken any specific action on the government’s say-so. To the contrary, they indicate that Meta and the government have regularly disagreed about what policies to implement and how to enforce them. See Murthy, 144 S. Ct. at 1987 (highlighting evidence “that White House officials had flagged content that did not violate company policy”). Even if Meta has removed or restricted some of the content of which the government disapproves, the evidence suggests that Meta “had independent incentives to moderate content and . . . exercised [its] own judgment” in so doing.

As for the fact that Meta offers a portal for some to submit reports, that doesn’t change the fact that it’s still judging those reports against its own policies and not just obeying the government.

That the government submitted requests for removal of specific content through a “portal” Meta created to facilitate such communication does not give rise to a plausible inference of joint action. Exactly the same was true in O’Handley, where Twitter had created a “Partner Support Portal” through which the government flagged posts to which it objected. 62 F.4th at 1160. Meta was entitled to encourage such input from the government as long as “the company’s employees decided how to utilize this information based on their own reading of the flagged posts.” Id. It does not become an agent of the government just because it decides that the CDC sometimes has a point.

The majority opinion also addresses the question of whether or not Meta was coerced. It first notes that if that were the issue, then Meta itself probably wouldn’t be the right defendant, the government would be. But then it notes the near total lack of evidence of coercion.

CHD has not alleged facts that allow us to infer that the government coerced Meta into implementing a specific policy. Instead, it cites statements by Members of Congress criticizing social media companies for allowing “misinformation” to spread on their platforms and urging them to combat such content because the government would hold them “accountable” if they did not. Like the “generalized federal concern[s]” in Mathis II, those statements do not establish coercion because they do not support the inference that the government pressured Meta into taking any specific action with respect to speech about vaccines. Mathis II, 75 F.3d at 502. Indeed, some of the statements on which CHD relies relate to alleged misinformation more generally, such as a statement from then-candidate Biden objecting to a Facebook ad that falsely claimed that he blackmailed Ukrainian officials. All CHD has pleaded is that Meta was aware of a generalized federal concern with misinformation on social media platforms and that Meta took steps to address that concern. See id. If Meta implemented its policy at least in part to stave off lawmakers’ efforts to regulate, it was allowed to do so without turning itself into an arm of the federal government.

To be honest, I’m not so sure of the last line there. If it’s true that Meta implemented policies because it wanted to avoid regulation, that strikes me as a potential First Amendment violation, but again, one that should be targeted at the government, not Meta.

The opinion also notes that angry letters from Rep. Adam Schiff and Senator Amy Klobuchar did not appear to cross the coercive line, despite being aggressive.

But in contrast to cases where courts have found coercion, the letters did not require Meta to take any particular action and did not threaten penalties for noncompliance….

Again, I think the opinion goes a bit too far here in suggesting that legislators mostly don’t have coercive power by themselves, giving them more leeway to send these kinds of letters.

Unlike “an executive official with unilateral power that could be wielded in an unfair way if the recipient did not acquiesce,” a single legislator lacks “unilateral regulatory authority.” Id. A letter from a legislator would therefore “more naturally be viewed as relying on her persuasive authority rather than on the coercive power of the government.”

I think that’s wrong. I’ve made the case that it’s bad when legislators threaten to punish companies for speech, and it’s frustrating that both Democrats and Republicans seem to do it regularly. Here, the 9th Circuit seems to bless that which is a bit frustrating and could lead to more attempts by legislators to suppress speech.

The Court then dismisses CHD’s absolutely laughable Section 230 state action theory. This was Rubenfeld’s baby. In January 2021, Rubenfeld co-authored one of the dumbest WSJ op-eds we’ve ever seen with a then mostly unknown “biotech exec” named Vivek Ramaswamy, arguing that Section 230 made social media companies into state actors. A few months later, Rubenfeld joined RFK Jr.’s legal team to push this theory in court.

It failed at the district court level and it fails here again on appeal.

The immunity from liability conferred by section 230 is undoubtedly a significant benefit to companies like Meta that operate social media platforms. It might even be the case that such platforms could not operate at their present scale without section 230. But many companies rely, in one way or another, on a favorable regulatory environment or the goodwill of the government. If that were enough for state action, every large government contractor would be a state actor. But that is not the law.

The opinion notes that this crazy theory is based on a near complete misunderstanding of case law and how Section 230 works. Indeed, the Court calls out this argument as “exceptionally odd.”

It would be exceptionally odd to say that the government, through section 230, has expressed any preference at all as to the removal of anti-vaccine speech, because the statute was enacted years before the government was concerned with speech related to vaccines, and the statute makes no reference to that kind of speech. Rather, as the text of section 230(c)(2)(A) makes clear—and as the title of the statute (i.e., the “Communications Decency Act”) confirms—a major concern of Congress was the ability of providers to restrict sexually explicit content, including forms of such content that enjoy constitutional protection. It is not difficult to find examples of Members of Congress expressing concern about sexually explicit but constitutionally protected content, and many providers, including Facebook, do in fact restrict it.See, e.g., 141 Cong. Rec. 22,045 (1995) (statement of Rep. Wyden) (“We are all against smut and pornography . . . .”); id. at 22,047 (statement of Rep. Goodlatte) (“Congress has a responsibility to help encourage the private sector to protect our children from being exposed to obscene and indecent material on the Internet.”); Shielding Children’s Retinas from Egregious Exposure on the Net (SCREEN) Act, S. 5259, 117th Cong. (2022); Adult Nudity and Sexual Activity, Meta, https://transparency.fb.com/policies/communitystandards/adult-nudity-sexual-activity [https://perma.cc/ SJ63-LNEA] (“We restrict the display of nudity or sexual activity because some people in our community may be sensitive to this type of content.”). While platforms may or may not share Congress’s moral concerns, they have independent commercial reasons to suppress sexually explicit content. “Such alignment does not transform private conduct into state action.”

Indeed, it points to the ridiculous logical conclusion of this Rubenfeld/Ramaswamy argument:

If we were to accept CHD’s argument, it is difficult to see why would-be purveyors of pornography would not be able to assert a First Amendment challenge on the theory that, viewed in light of section 230, statements from lawmakers urging internet providers to restrict sexually explicit material have somehow made Meta a state actor when it excludes constitutionally protected pornography from Facebook. So far as we are aware, no court has ever accepted such a theory

Furthermore, the Court makes clear that moderation decisions are up to the private companies, not the courts. And if people don’t like it, the answer is market forces and competition.

Our decision should not be taken as an endorsement of Meta’s policies about what content to restrict on Facebook. It is for the owners of social media platforms, not for us, to decide what, if any, limits should apply to speech on those platforms. That does not mean that such decisions are wholly unchecked, only that the necessary checks come from competition in the market—including, as we have seen, in the market for corporate control. If competition is thought to be inadequate, it may be a subject for antitrust litigation, or perhaps for appropriate legislation or regulation. But it is not up to the courts to supervise social media platforms through the blunt instrument of taking First Amendment doctrines developed for the government and applying them to private companies. Whether the result is “good or bad policy,” that limitation on the power of the courts is a “fundamental fact of our political order,” and it dictates our decision today

Even more ridiculous than the claims around content being taken down, CHD also claimed that the fact checks on their posts violated [checks notes… checks notes again] the Lanham Act, which is the law that covers things like trademark infringement and some forms of misleading advertising. The Court here basically does a “what the fuck are you guys talking about” to Kennedy and Rubenfeld.

By that definition, Meta did not engage in “commercial speech”—and, thus, was not acting “in commercial advertising or promotion”—when it labeled some of CHD’s posts false or directed users to fact-checking websites. Meta’s commentary on CHD’s posts did not represent an effort to advertise or promote anything, and it did not propose any commercial transaction, even indirectly.

And just to make it even dumber, CHD also had a RICO claim. Because, of course they did. Yet again, we will point you to Ken White’s “It’s not RICO dammit” lawsplainer, but the Court here does its own version:

The causal chain that CHD proposes is, to put it mildly, indirect. CHD contends that Meta deceived Facebook users who visited CHD’s page by mislabeling its posts as false. The labels that Meta placed on CHD’s posts included links to fact-checkers’ websites. If a user followed a link, the factchecker’s website would display an explanation of the alleged falsity in CHD’s post. On the side of the page, the fact-checker had a donation button for the organization. Meanwhile, Meta had disabled the donation button on CHD’s Facebook page. If a user decided to donate to the fact-checking organization, CHD maintains, that money would come out of CHD’s pocket, because CHD and factcheckers allegedly compete for donations in the field of health information.

The alleged fraud— Meta’s mislabeling of CHD’s posts— is several steps removed from the conduct directly responsible for CHD’s asserted injury: users’ depriving CHD of their donation dollars. At a minimum, the sequence relies on users’ independent propensities to intend to donate to CHD, click the link to a fact-checker’s site, and be moved to reallocate funds to that organization. This causal chain is far too attenuated to establish the direct relationship that RICO requires. Proximate cause “is meant to prevent these types of intricate, uncertain inquiries from overrunning RICO litigation.” Anza, 547 U.S. at 460.

CHD’s theory also strains credulity. It is not plausible that someone contemplating donating to CHD would look at CHD’s Facebook page, see the warning label placed there, and decide instead to donate to . . . a fact-checking organization. See Twombly, 550 U.S. at 555. The district court noted that CHD did not allege that any visitors to its page had in fact donated to other organizations because of Meta’s fraudulent scheme. CHD is correct that an actual transfer of money or property is not an element of wire fraud, as “[t]he wire fraud statute punishes the scheme, not its success.” Pasquantino v. United States, 544 U.S. 349, 371 (2005) (alteration in original) (quoting United States v. Pierce, 224 F.3d 158, 166 (2d Cir. 2000)). But the fact that no donations were diverted provides at least some reason to think that no one would have expected or intended the diversion of donations.

I love how the judge includes the… incredulous pause ellipses in that last highlighted section.

Oh, and I have to go back to one point. CHD had originally offered an even dumber RICO theory which it dropped, but the Court still mentions it:

In the complaint, CHD described a scheme whereby Meta placed warning labels on CHD’s posts with the intent to “clear the field” of CHD’s alternative point of view, thus keeping vaccine manufacturers in business so that they would buy ads on Facebook and ensure that Zuckerberg obtained a return on his investments in vaccine technology.

That’s brain worm logic speaking, folks.

There is a partial dissent from (Trump-appointed, natch) Judge Daniel Collins, who says that maybe, if you squint, there is a legitimate First Amendment claim. In part, this is because Collins thinks CHD should be able to submit additional material that wasn’t heard by the district court, which is not how any of this tends to work. You have to present everything at the lower court. The appeals court isn’t supposed to consider any new material beyond, say, new court rulings that might impact this ruling.

Collins then also seems to buy into Rubenfeld’s nutty 230-makes-you-a-state actor argument. He goes on for a while giving the history of Section 230 (including a footnote pointing out, correctly but pedantically, that it’s Section 230 of the Communications Act of 1934, but not Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act as most people call it — a point that only certain law professors talk about). The history is mostly accurate, highlighting the Stratton Oakmont decision and how it would be impossible to run an internet service if that had stood.

But then… it takes some leaps. It takes some giant leaps with massive factual errors. Embarrassing for a judge to be making:

The truly gigantic scale of Meta’s platforms, and the enormous power that Meta thereby exercises over the speech of others, are thus direct consequences of, and critically dependent upon, the distinctive immunity reflected in § 230. That is, because such massive third-party-speech platforms could not operate on such a scale in the absence of something like § 230, the very ability of Meta to exercise such unrestrained power to censor the speech of so many tens of millions of other people exists only by virtue of the legislative grace reflected in § 230’s broad immunity. Moreover, as the above discussion makes clear, it was Congress’s declared purpose, in conferring such immunity, to allow platform operators to exercise this sort of wide discretion about what speech to allow and what to remove. In this respect, the immunity granted by § 230 differs critically from other government-enabled benefits, such as the limited liability associated with the corporate form. The generic benefits of incorporation are available to all for nearly every kind of substantive endeavor, and the limitation of liability associated with incorporation thus constitutes a form of generally applicable non-speech regulation. In sharp contrast, both in its purpose and in its effect, § 230’s immunity is entirely a speech-related benefit—it is, by its very design, an immunity created precisely to give its beneficiaries the practical ability to censor the speech of large numbers of other persons.7 Against this backdrop, whenever Meta selectively censors the speech of third parties on its massive platforms, it is quite literally exercising a government-conferred special power over the speech of millions of others. The same simply cannot be said of newspapers making decisions about what stories to run or bookstores choosing what books to carry

I do not suggest that there is anything inappropriate in Meta’s having taken advantage of § 230’s immunity in building its mega-platforms. On the contrary, the fact that it and other companies have built such widely accessible platforms has created unprecedented practical opportunities for ordinary individuals to share their ideas with the world at large. That is, in a sense, exactly what § 230 aimed to accomplish, and in that particular respect the statute has been a success. But it is important to keep in mind that the vast practical power that Meta exercises over the speech of millions of others ultimately rests on a government-granted privilege to which Meta is not constitutionally entitled.

Those highlighted sections are simply incorrect. Meta is constitutionally entitled to the ability to moderate thanks to the First Amendment. Section 230 simplifies the procedural aspects of it, in that companies need not fight an expensive and drawn-out First Amendment battle over it, as Section 230 shortcuts that procedurally by granting the immunity that ends cases much faster. Though it ends them the same way it would end otherwise, thanks to the First Amendment.

So, basically the key point that Judge Collins rests his dissent on is fundamentally incorrect. And it’s odd that he ignores the recent Moody ruling and even last year’s Taamneh ruling that basically explains why this is wrong.

Collins also seems to fall for the false idea that Section 230 requires a site to be a platform or a publisher, which is just wrong.

Rather, because its ability to operate its massive platform rests dispositively on the immunity granted as a matter of legislative grace in § 230, Meta is a bit of a novel legal chimera: it has the immunity of a conduit with respect to third-party speech, based precisely on the overriding legal premise that it is not a publisher; its platforms’ massive scale and general availability to the public further make Meta resemble a conduit more than any sort of publisher; but Meta has, as a practical matter, a statutory freedom to suppress or delete any third-party speech while remaining liable only for its own affirmative speech

But that’s literally wrong as well. Despite how it’s covered by many politicians and the media, Section 230 does not say that a website is not a publisher. It says that it shall not be treated as a publisher for third-party content even though it is engaging in publishing activities.

Incredibly, Collins even cites (earlier in his dissent) the 9th Circuit’s Barnes ruling which lays this out. In Barnes, the 9th Circuit is quite clear that Section 230 protects Yahoo from being held liable for third-party content explicitly because it is doing everything a publisher would do. Section 230 just removes liability from third-party content so that a website is not treated as a publisher, even when it is acting as a publisher.

In that case, the Court laid out all the reasons why Yahoo was acting as a publisher. It called what Yahoo engaged in “action that is quintessentially that of a publisher.” Then, it notes it couldn’t be held liable for those activities thanks to Section 230 (eventually Yahoo did lose that case, but under a different legal theory, related to promissory estoppel, but that’s another issue).

Collins even cites this very language from the Barnes decision:

As we stated in Barnes, “removing content is something publishers do, and to impose liability on the basis of such conduct necessarily involves treating the liable party as a publisher of the content it failed to remove.” Id. “Subsection (c)(1), by itself, shields from liability all publication decisions, whether to edit, to remove, or to post, with respect to content generated entirely by third parties.”

So it’s bizarre that pages later, Collins falsely claims that Section 230 means that Meta is claiming not to be a publisher. As the Barnes case makes clear, Section 230 says you don’t treat the publisher of third-party content as a publisher of first-party content. But they’re both publishers of a sort. And Collins seemed to acknowledge this 20 pages earlier… and then… forgot?

Thankfully, Collin’s dissent is only a dissent and not the majority.

Still, as we noted back in May, RFK Jr. and Rubenfeld teamed up a second time to sue Meta yet again, once again claiming that Meta moderating him is a First Amendment violation. That’s a wholly different lawsuit, with the major difference being… that because RFK Jr. is a presidential candidate (lol), somehow this now makes it a First Amendment violation for Meta to moderate his nonsense.

So the Ninth Circuit should have yet another chance to explain the First Amendment to them both yet again.

More Law-Related Stories From Techdirt:

L’oreal Disputes Late Trademark Renewal Over ‘NKD’ Brand, With Which They’ve Coexisted For Years

Australian Feds Spent More Than $500,000 Trying To Lock Up An Autistic 13-Year-Old On Terrorism Charges

Utah’s Book Banning Law Claims Judy Blume, Five Other Female Authors As Its First Victims