Legacy Matters

Among a president’s most enduring legacies are the federal judges they appoint—particularly Supreme Court justices. This permanence stems from life tenure, a constitutional provision that ensures judicial independence but also transforms each appointment into a generational bet on the nation’s legal future.

Yet history is littered with presidential miscalculations. President Eisenhower famously called his appointment of Earl Warren to Chief Justice one of his “biggest mistakes,” as Warren became a liberal stalwart for over a decade. Justices Stevens and Souter, both nominated by Republican presidents, evolved into some of the Court’s most liberal members. Had Republican presidents consistently installed reliably conservative justices since the mid-20th century, the Court would have been exponentially more conservative than it actually was.

4 Ways Your Firm Can Build Economic Resilience

It’s the key to long-term success in an uncertain business climate.

But presidential legacy is only part of the story. The judges themselves have developed their own succession strategies. In recent years, a striking pattern has emerged: Supreme Court justices now appear ready to retire only with tacit—or perhaps explicit—assurances that they will be replaced by someone they helped shape, typically a former clerk. Since Justice Kennedy retired after the 2017 term, this has become the norm rather than the exception.

Kennedy’s retirement exemplified this new dynamic. He secured not one but two former clerks in succession: Justice Gorsuch filled Justice Scalia’s seat, which had remained vacant longer than any in Court history, and Kennedy’s own seat went to Justice Kavanaugh. These consecutive Kennedy-clerk appointments represented a carefully orchestrated transition, a carrot from President Trump to convince Kennedy to step down with his legacy intact. For Trump, the bargain was equally advantageous: he could install more consistently conservative justices than Kennedy, who had occasionally sided with liberals on consequential civil liberties cases like the same-sex marriage decision in Obergefell v. Hodges.

The pattern continued with Justice Barrett, a Scalia clerk, replacing Justice Ginsburg after her death, and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, a Breyer clerk, succeeding her former mentor. Based on this emerging template, I previously wrote about how I anticipate that President Trump might appoint Judge Ho or Judge Rao—both Thomas clerks—to fill Justice Thomas’s seat, and Judge Oldham, an Alito clerk, to succeed Justice Alito should either retire during Trump’s tenure.

This pattern of legacy-based decisions augments the theory of strategic retirement, where federal judges retire under likeminded presidents to ensure the balance of each court does not shift in the opposing ideological direction. I wrote about the possibility of this occurring and how the consequence of Justice Barrett potentially filling this seat prior to Justice Ginsburg’s death. Many others also contemporaneously, previously, and after me wrote about the potential and actual downstream effects of Justice Ginsburg’s decision.

How Legisway Helps In-House Teams Manage All Legal Matters In One Trusted Place

Operate with AI driven insights, legal intake, unified content and modular scalability to transform efficiency and clarity.

At the bottom of it all, this highlights the importance of federal judgeships, not only the president, but more importantly to future generations and to the embedding of particular values and preferences within the federal judiciary for decades to come.

Consequences and Methodology

The importance of federal judge replacements reaches beyond presidential legacy. This analysis examines which current and former federal judges have placed the most former clerks on the federal bench, using data from the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges maintained by the Federal Judicial Center.

Building on previous analysis of federal judges appointed from Reagan through the current Trump administration, this examination focuses specifically on judicial legacy through clerk placement. After correcting for inconsistencies in how the Biographical Directory formatted clerkship entries (First Liberty’s Hiram Sasser noted in a comment some of the missing entries in a previous post which I now corrected and made freely accessible), the data reveals a clear hierarchy of influence across district, appeals, and Supreme Court levels.

Presidential Appointments: The Foundation of Judicial Legacy

If presidents’ legacies are bound to their judicial appointments—especially Supreme Court justices—then the number of justices each president installs becomes a meaningful measure of lasting influence. While not every appointment produces the jurisprudence a president envisions, each represents an attempt to implant their vision of constitutional interpretation.

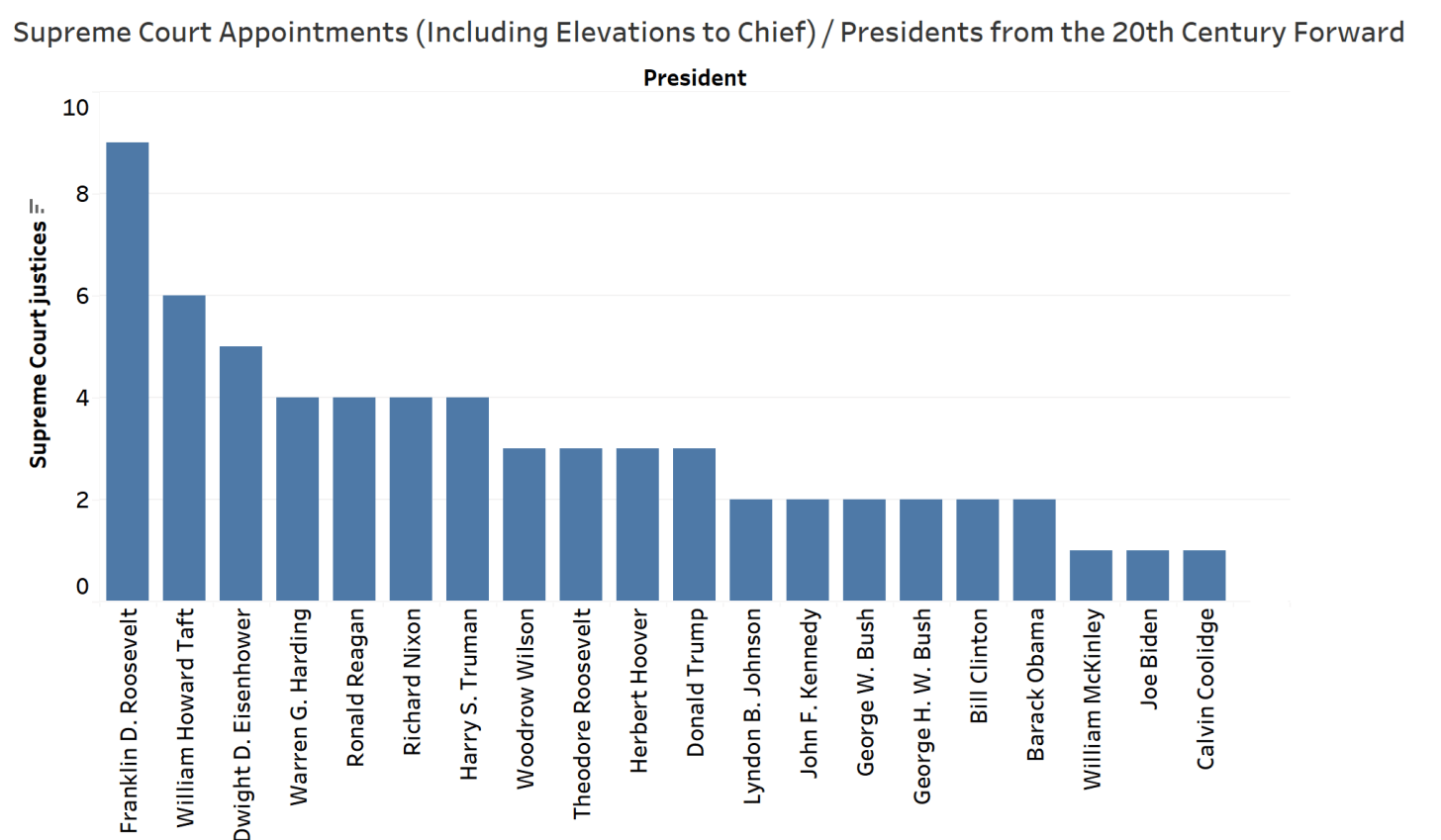

Among 20th and 21st-century presidents, Franklin D. Roosevelt stands as the overwhelming leader, appointing nine Supreme Court justices during his unprecedented four terms. Taft follows with six appointments, while Eisenhower made five. More recent presidents show markedly fewer opportunities although Trump with three in his first term was a clear outlier.

These numbers reflect not just presidential priorities but the vagaries of timing—how long justices serve, when they choose to retire, and the unpredictability of death. Roosevelt’s nine appointments came during the constitutional crisis of the New Deal, while recent presidents have faced a Court where justices increasingly time their retirements strategically, often waiting for a president of their preferred ideology.

Supreme Court: Where Judicial Dynasties Begin

The downstream effects of Supreme Court clerkships can reshape American law across generations. Consider the lineage from Justice Robert Jackson to William Rehnquist, who clerked for Jackson, to John Roberts, who clerked for Rehnquist and now serves as Chief Justice. This chain of influence spans more than half a century, with each generation of jurists passing their interpretive methods to the next.

Supreme Court clerkships represent a relatively modern phenomenon, emerging primarily as the Court evolved through the 20th century. The number of clerks per justice has steadily increased, expanding the pool of potential judicial heirs. The data reveals which justices have been most successful at placing their clerks throughout the federal judiciary.

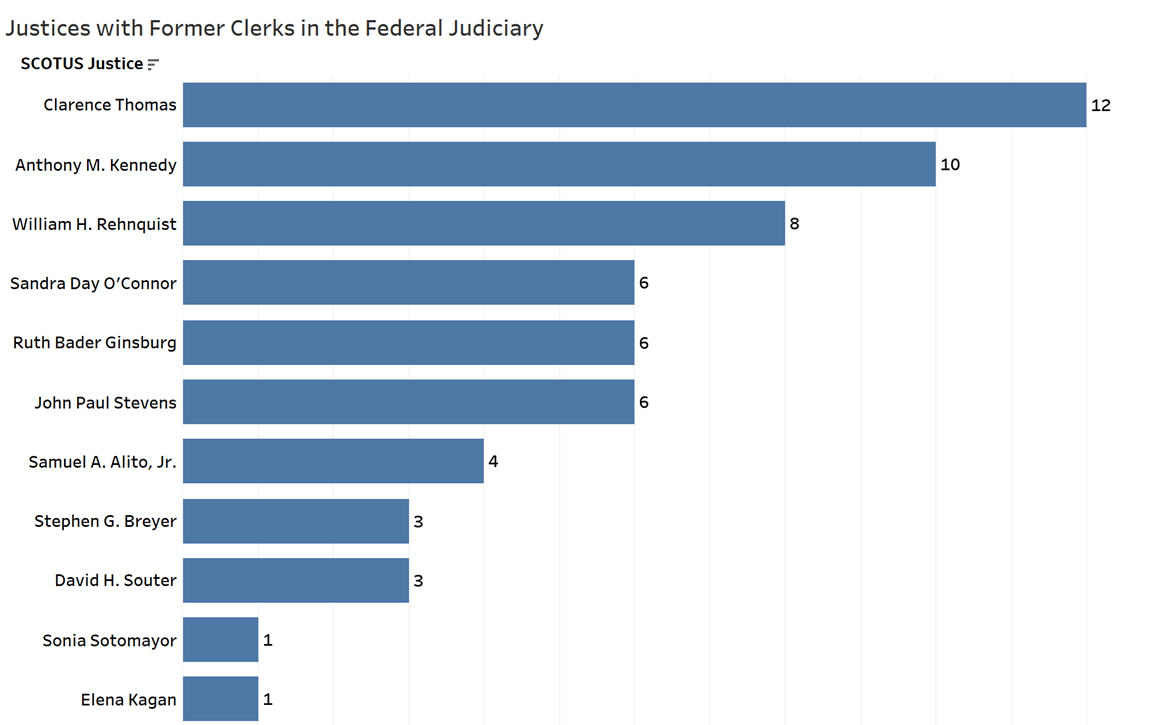

Justice Clarence Thomas leads by a substantial margin, with twelve former clerks now serving as federal judges—a testament both to his long tenure and his deliberate cultivation of conservative judicial talent. Justice Anthony Kennedy follows with ten clerk-judges, including the two Supreme Court justices mentioned earlier. Justice Rehnquist placed eight former clerks, continuing his influence even after his 2005 death.

Justices O’Connor and Ginsburg each count six former clerks in the federal judiciary, while Justice Stevens also placed six. Justice Alito has four clerk-judges, while Justices Breyer and Souter each have three. Perhaps most surprisingly, given his position as Chief Justice, John Roberts has not yet seen a former clerk become a federal judge according to Federal Judicial Center data.

Originalism Across Generations: Scalia to Barrett

The transmission of judicial philosophy from justice to clerk-turned-justice reveals itself most clearly in interpretive methodology. Justice Scalia’s originalist approach in McDonald v. City of Chicago exemplified his commitment to understanding constitutional provisions through their historical meaning. Writing about the Second Amendment’s application to the states, Scalia emphasized the settled understanding that the Bill of Rights originally constrained only the federal government. His opinion methodically traced the historical record, citing Chief Justice Marshall’s 1833 opinion in Barron v. Baltimore and noting that the question was “of great importance” but “not of much difficulty.” Scalia’s analysis embodied his conviction that constitutional interpretation must begin with original public meaning, regardless of whether that meaning comports with modern sensibilities.

Justice Barrett, who clerked for Scalia, has inherited this originalist framework but applies it with a notably different rhetorical style and, at times, different conclusions. In Haaland v. Brackeen, her majority opinion defending the Indian Child Welfare Act demonstrated both continuity and evolution in originalist methodology. When petitioners challenged ICWA by arguing it was inconsistent with the Constitution’s original meaning, Barrett’s response revealed a more institutionally cautious approach than her mentor might have taken. She wrote that petitioners “offer no account of how their argument fits within the landscape of our case law” and noted they “neither ask us to overrule the precedent they criticize nor try to reconcile their approach with it.”

This represents a subtle but significant shift from Scalia’s more aggressive originalism. Where Scalia often championed overturning precedents he viewed as wrongly decided, Barrett demanded that litigants reckon with existing doctrine and explain the broader implications of their originalist claims. Her question—”Would it undermine established cases and statutes? If so, which ones?”—reflects an originalism tempered by concerns about legal stability and institutional legitimacy. The clerk has inherited the mentor’s interpretive framework but adapted it to a Court increasingly conscious of its public standing.

Courts of Appeals: The Proving Ground

Circuit judges occupy a unique position in the federal judiciary. While they lack the Supreme Court’s ultimate authority, they effectively have the final word in the vast majority of federal cases. Their opinions shape entire areas of law within their circuits, making them powerful vectors for transmitting judicial philosophy. The data on circuit judges with three or more former clerks now serving as federal judges reveals who has been most effective at extending their influence.

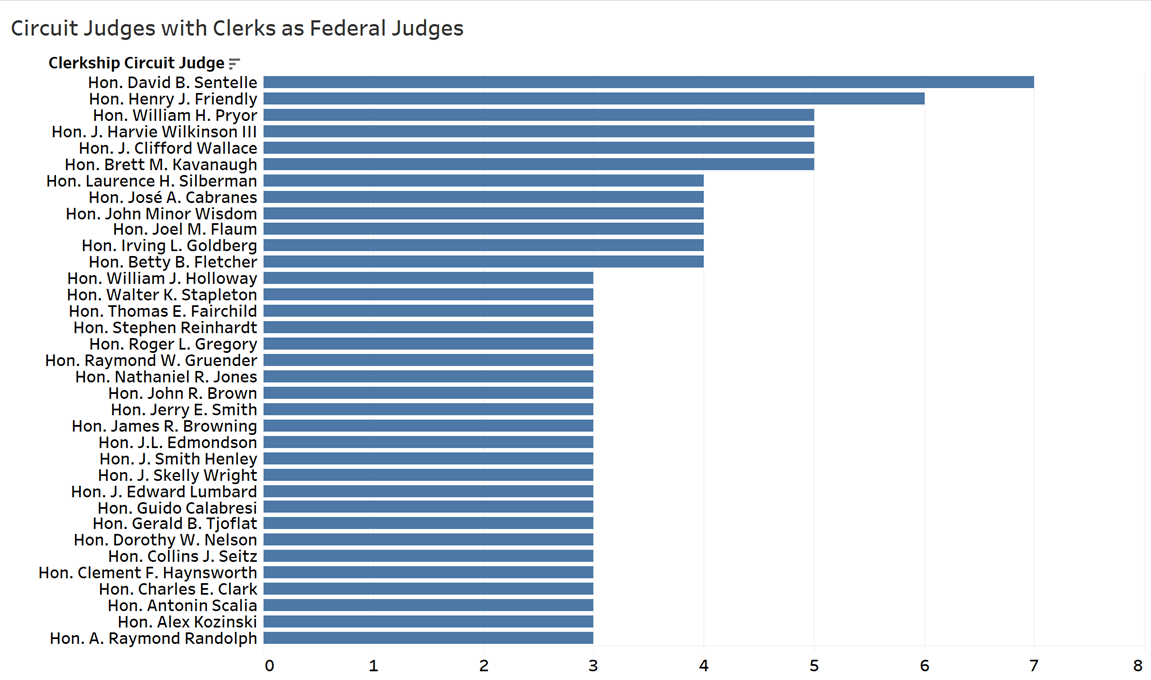

Judge David B. Sentelle of the D.C. Circuit leads all circuit judges with seven former clerks in the federal judiciary—an extraordinary record that reflects both his long service and his role in shaping conservative legal thought. Judge Henry J. Friendly of the Second Circuit and Judge William H. Pryor of the Eleventh Circuit follow with six clerk-judges each. Several other prominent circuit judges, including J. Harvie Wilkinson III, J. Clifford Wallace, and Brett Kavanaugh (before his Supreme Court appointment), have placed five former clerks.

The concentration at the top of this list is striking. While thirty-five circuit judges have placed at least three former clerks, the gap between Sentelle’s seven and the next tier reflects his particular success at cultivating judicial talent. Many of these judges served or continue to serve on influential circuits—the D.C., Fourth, and Ninth Circuits appear frequently—where high-profile cases and proximity to political power create natural pipelines to future judicial appointments.

The Textualist Thread: Sentelle to Gorsuch

The connection between Judge Sentelle and Justice Gorsuch illuminates how circuit court judges transmit interpretive approaches that later appear in Supreme Court jurisprudence. In NLRB v. Canning, Judge Sentelle’s opinion for the D.C. Circuit panel exemplified his textualist methodology. Interpreting the Recess Appointments Clause, Sentelle focused on the plain meaning of “happen,” construing it to mean “arise” and emphasizing textual consistency across constitutional provisions. He wrote that “inconsistency [within the Constitution] is to be implied only where the context clearly requires it,” citing a 1949 precedent. For Sentelle, the clause’s text demanded that a qualifying vacancy must have “come to pass or arisen ‘during the Recess’”—a reading he found consistent with the Senate Vacancies Clause while the Board’s interpretation was not.

Justice Gorsuch’s approach in Bostock v. Clayton County echoes his former mentor’s commitment to text over expected applications. Writing for the Court in the landmark Title VII case, Gorsuch rejected the employers’ argument that Congress could not have intended the statute to cover sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination. He acknowledged the employers “take pains to couch their argument in terms of seeking to honor the statute’s ‘expected applications’ rather than vindicate its ‘legislative intent,’” but insisted “the concepts are closely related.” Gorsuch’s retort—”However framed, the employer’s logic impermissibly seeks to displace the plain meaning of the law in favor of something lying beyond it”—could have been written by Sentelle himself.

Yet Gorsuch’s opinion in Bostock also reveals how judicial philosophy evolves across generations. While Sentelle’s textualism in Canning served conservative ends (limiting executive power under a Democratic president), Gorsuch’s textualism in Bostock produced a liberal outcome that many conservatives opposed. Both judges prioritized text over expected applications, but Gorsuch demonstrated a willingness to follow the text even when it led somewhere his mentor’s ideological allies found uncomfortable. The methodology remains consistent; the outcomes can surprise.

District Courts: Building From the Ground Up

District court judges handle the vast bulk of federal litigation, conducting trials, managing discovery, and making the factual findings that appellate courts later review. While individual district judges may lack the precedential authority of their appellate colleagues, collectively they shape how federal law operates on the ground. The judges who have placed multiple former clerks on the federal bench represent an often-overlooked tier of judicial influence.

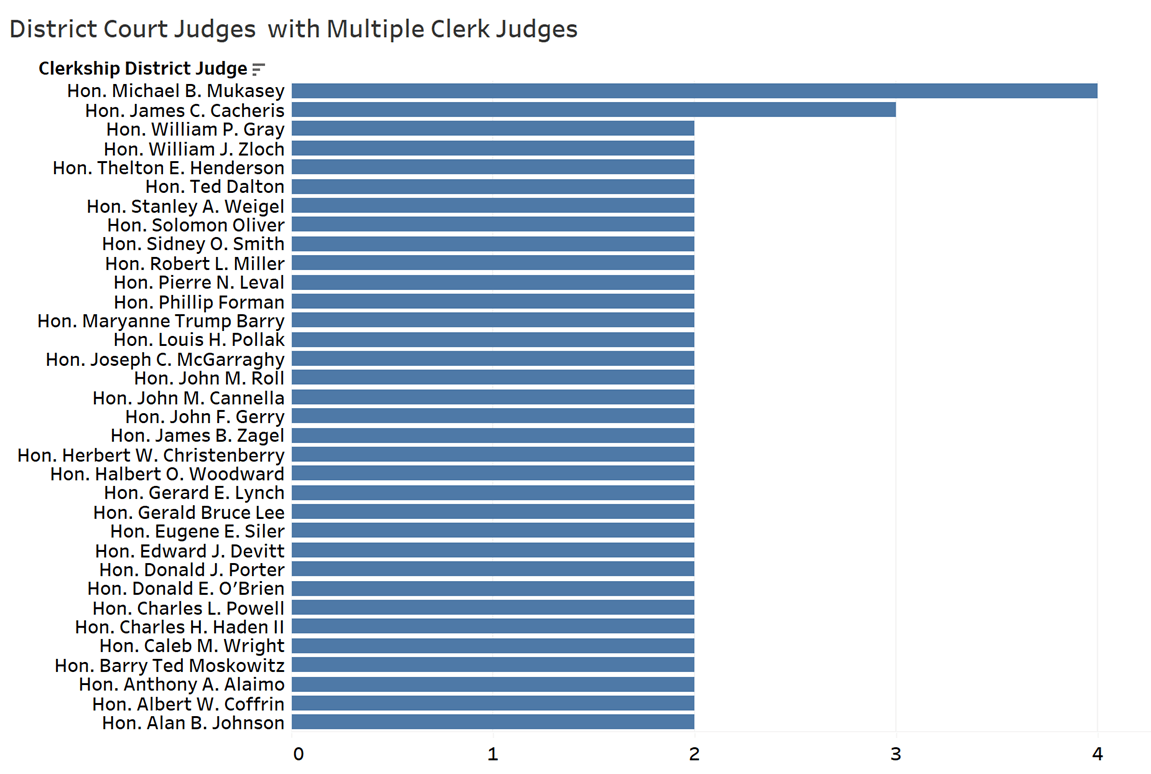

The data reveals a more dispersed pattern than at the circuit or Supreme Court levels. Judge Michael B. Mukasey of the Southern District of New York leads with four former clerks in the federal judiciary—an impressive figure given that district judges typically have fewer clerks and less name recognition than their appellate counterparts. Judge James C. Cacheris of the Eastern District of Virginia follows with three clerk-judges, while numerous other district judges have placed two former clerks.

The geographic concentration is notable. Many judges on this list served in high-profile districts—the Southern District of New York, the Eastern District of Virginia, and the District of Columbia—where challenging cases and visibility create opportunities for clerks to distinguish themselves. Judges in these districts often handle national security cases, complex white-collar prosecutions, and politically sensitive litigation, providing clerks with experience that later recommends them for judicial appointments.

First Amendment Doctrine: From Mukasey to Pan

The judicial lineage from Judge Mukasey to Judge Patricia Millett Pan of the D.C. Circuit demonstrates how district court approaches to constitutional doctrine can influence appellate jurisprudence. In Nonnenmann v. City of New York, Judge Mukasey granted summary judgment on First Amendment claims with a terse analysis that exemplified his pragmatic approach. He concluded that the plaintiff’s speech “did not address a constitutionally protected issue of public concern,” disposing of the claim in a single sentence within a broader opinion rejecting multiple theories of liability. Mukasey’s treatment reflected the district court’s role: apply established doctrine efficiently, manage complex dockets, and move cases toward resolution.

Judge Pan’s opinion in Ateba v. Leavitt reveals a more elaborate First Amendment framework, though one that reaches a similarly government-friendly conclusion. The case involved a journalist’s challenge to the White House hard pass policy. Pan acknowledged the First Amendment concerns but applied the established reasonableness standard, concluding that conditioning fuller access on Senate Daily Press Gallery accreditation was “both reasonable and viewpoint neutral.” Her analysis engaged more deeply with the constitutional doctrine, addressing arguments about unbridled discretion and procedural protections while ultimately deferring to the government’s access policy. Much of the difference in depth of analysis may relate to the objectives and extent of constitutional interpretation of district court versus appeals court judge.

The comparison reveals both continuity and evolution. Both judges applied First Amendment doctrine to uphold government restrictions, and both wrote with relative brevity. Yet Pan’s opinion shows the more elaborate reasoning expected at the appellate level, engaging with constitutional standards and potential objections while Mukasey’s district court opinion moved quickly to disposition. The student has learned to elaborate on the framework while reaching conclusions that likely would satisfy her mentor.

Implications: The Self-Replicating Judiciary

These patterns of clerk succession point toward a fundamental transformation in how the federal judiciary perpetuates itself. What began as an informal preference for continuity has evolved into something approaching a self-replicating system, where judicial philosophies pass from one generation to the next through carefully cultivated mentor-clerk relationships. The implications extend far beyond individual careers or even the ideological balance of particular courts.

First, the clerk pipeline is creating unprecedented ideological coherence within judicial camps. When Justice Scalia’s originalism passes to Justice Barrett, or Judge Sentelle’s textualism appears in Justice Gorsuch’s opinions, or Judge Mukasey’s First Amendment skepticism echoes in Judge Pan’s rulings, we see not just individual judges but schools of thought reproducing themselves across levels of the federal judiciary. This coherence increases predictability—probably a good thing for the rule of law—but also reduces the kind of creative tension that historically produced judicial evolution.

Second, the emphasis on clerk credentials may be narrowing the diversity of judicial backgrounds and experiences. When Supreme Court seats increasingly go to former clerks of previous justices, and circuit judgeships follow similar patterns, the federal judiciary risks becoming a closed system that prizes insider credentials over other forms of distinction. A lawyer who built a successful trial practice, or led a civil rights organization, or served as a state judge may find themselves disadvantaged compared to someone who clerked for the right justice at the right time.

Third, strategic retirement is likely to become even more entrenched as justices and judges see their former clerks successfully ascend to higher courts. Why risk having your seat filled by someone who will dismantle your life’s work when you can time your retirement to ensure a former clerk succeeds you? This calculus transforms judicial service from a commitment to decide cases until incapacity into a more strategic career management decision. The Court becomes less independent of politics, not more, as retirements increasingly align with electoral cycles.

Fourth, the concentration visible in these numbers—particularly Justice Thomas’s twelve clerk-judges and Judge Sentelle’s seven—suggests that a relatively small number of judges are having outsized influence on the composition of the federal bench. This has the effect of concentrating enormous power in the hands of a few individuals to shape the judiciary’s future direction, particularly when combined with ideologically motivated appointment processes.

Looking forward, several questions demand attention. Will this trend continue to accelerate? Will judges who lack Supreme Court or prominent circuit clerkships find their paths to the bench increasingly blocked? Will the public’s perception of judicial independence suffer?

Perhaps most intriguingly, will the next generation of judges—those who clerked for justices who themselves were clerks—develop distinctive approaches that break from their mentors’ methods? Justice Gorsuch’s surprising Bostock opinion suggests that judicial philosophy, even when transmitted through close mentorship, remains more dynamic and unpredictable than a simple model of replication would suggest. The clerks may learn their mentors’ methods, but they apply those methods in new contexts, facing new questions, and sometimes reach conclusions that would have shocked their teachers.

The data presented here captures a moment in the evolution of the federal judiciary—a moment when the clerk pipeline has become visible enough to analyze but perhaps not yet so entrenched that it cannot be questioned or redirected. As President Trump’s second administration considers judicial appointments, and as sitting justices contemplate their retirement timing, these patterns of succession will likely intensify. Whether that produces a judiciary that is more coherent and predictable, or one that is closed and self-referential, remains to be seen.

What seems certain is that the era of unpredictable judicial appointments—when Republican presidents might appoint liberal justices or when judges might dramatically evolve on the bench—is largely over. The clerk pipeline, combined with more sophisticated vetting processes and strategic retirement decisions, has made judicial appointments far more predictable. We know not just what ideology a nominee holds, but where they learned it, from whom, and how they are likely to apply it. The federal judiciary is becoming, for better or worse, a self-perpetuating institution where each generation of judges carefully selects and trains the next.

Click here to read more from Legalytics…

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. Check out more of his writing at Legalytics and Empirical SCOTUS. For more information, write Adam at [email protected]. Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.