Sesame Street Loses Trademark Lawsuit Over 'Happytime Murders' Film To Muppet Lawyer, Fred, Esq.

When will people learn that censorship attempts only draw more attention to the issue?

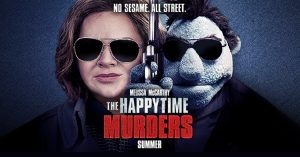

I think my favorite intellectual property story of the year so far involves an upcoming R-rated film, Happytime Murders, which envisions the lives of muppets when they’re not being filmed, set in a crime story with Melissa McCarthy playing the detective. Think Who Framed Roger Rabbit crossed with Avenue Q. But the really awesome part of this story has nothing to do with the movie itself, but rather the response of the production company, STX Films after being sued.

I think my favorite intellectual property story of the year so far involves an upcoming R-rated film, Happytime Murders, which envisions the lives of muppets when they’re not being filmed, set in a crime story with Melissa McCarthy playing the detective. Think Who Framed Roger Rabbit crossed with Avenue Q. But the really awesome part of this story has nothing to do with the movie itself, but rather the response of the production company, STX Films after being sued.

STX Films released a trailer for Happytime Murders, and were promptly hit by a trademark lawsuit by Sesame Workshop, the rightholder to the kids’ show Sesame Street. Sesame Workshop filed for a temporary restraining order alleging:

Defendants’ widely distributed marketing campaign features a just-released trailer with explicit, profane, drug-using, misogynistic, violent, copulating, and even ejaculating puppets, along with the tagline, “NO SESAME. ALL STREET.” . . . they are distributing a trailer that deliberately confuses consumers into mistakenly believing that Sesame is associated with, has allowed, or has even endorsed or produced the movie and tarnishes Sesame’s brand.

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

Of course, STX Films quickly defended itself from these crazy claims. Here’s where the story gets good: this case probably got more attention than it may otherwise have, due to the intervention of muppet lawyer Fred, Esq. — as in a muppet who is a lawyer, not a lawyer representing muppets — who represents the producers of Happytime Murders. Yes, STX has actual human lawyers for court, but from a marketing perspective, STX’s response is pretty awesome because who isn’t going to pay attention to a muppet lawyer, especially one putting out statements like this one opposing a restraining order:

The Application may be best summed up as, “NO FACTS. ALL ARGUMENT.”

And Fred, Esq. is certainly correct. The tagline explicitly disclaims connection to Sesame Street, rather than trying to confuse consumers. The line says no Sesame, in a clever turn of phrase intending to distinguish from the happiness of sunny days, sweepin’ the clouds away. Fred, Esq. continues, “It did not occur to STX that a viewer would see and hear ‘NO SESAME’ and think ‘YES SESAME.’”

The way the words Sesame Street are being used by Happytime Murders marketing also doesn’t use the exact phrase “Sesame Street,” and reasonable consumers are not going to confuse the two. To be clear, it’s not like Happytime Murders features popular Sesame Street muppets like Elmo or Bert and Ernie, so there’s no risk of confusion there, either.

Sponsored

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Happytime Murders and the Sesame Street franchise are clearly different, even if the words “Sesame” and “Street” appear in the marketing materials. They are marketed to completely different audiences; I don’t expect to find Happytime Murders merchandise in the toy aisle. Happytime Murders is clearly R-rated and it’s not like it’s the first time muppets, puppets, or cartoons have been used in clearly adult-themed films.

Trademark, by design, protects consumers by ensuring that they are not confused or misled. If I purchase a trademarked product, I’m paying for an expected standard of quality. It protects the owner of the trademarks, who might invest in marketing and branding to promote their products and don’t want their brand diluted by inferior products. But just as with any other form of intellectual property, the power of trademarks is not without limits, as Sesame found out.

District Court Judge Vernon Broderick rejected Sesame Workshop’s request for a TRO, stating that the use of “No Sesame. All Street.” was not trademark infringement but, rather, “a humorous, pithy way” of distinguishing Happytime Murders from Sesame Street. One day later, Sesame dropped their claims. Of course, in initiating the lawsuit in the first place, Sesame only drew more attention to the movie. When will people learn that censorship attempts only draw more attention to the issue?

Another example comes to mind: Do you all remember when comedian Al Franken wrote the book, Lies, and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them: A Fair and Balanced Look at the Right (way back in 2003, well before he would become a United States Senator, before resigning over sexual misconduct allegations), and Fox News sued him over the use of the phrase “fair and balanced”? Not only did Fox News lose its trademark case against Franken, but the book shot up the bestseller list, occupying the number 1 slot (up from number 489 prior to the lawsuit) thanks to all the extra attention. In fact, the publisher moved up the release date and ordered extra printings.

In the Fox News case, Judge Chin took the network to task in a court proceeding that was filled with laughter after several outlandish claims, such as when Fox’s attorney said the message of Franken’s book was ambiguous, in response to Chin’s incredulity that a reasonable consumer would actually think that conservative commentator Bill O’Reilly was endorsing a book with the word “lies” written over his face. Chin, siding with Franken, called Fox News’s motion “wholly without merit.”

Sponsored

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

I have to admit, I probably wouldn’t have read Franken’s book without all the extra publicity Fox News created. And, I would have had no interest in watching the Happytime Murders trailer. But the Streisand effect creates such a buzz that my curiosity is piqued, and all because of these meritless trademark claims.

Krista L. Cox is a policy attorney who has spent her career working for non-profit organizations and associations. She has expertise in copyright, patent, and intellectual property enforcement law, as well as international trade. She currently works for a non-profit member association advocating for balanced copyright. You can reach her at kristay@gmail.com.