You Can’t Copyright An Idea: Pirates Of The Caribbean Edition

Sorry, but stock characters and general plotlines are not eligible for copyright.

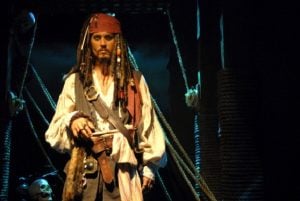

(Photo by Jason Kempin/FilmMagic)

Back in 2003, Disney released the first in the highly popular Pirates of the Caribbean franchise. The first film, Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl, starred Johnny Depp as the lead swashbuckler, Jack Sparrow, with Keira Knightly and Orlando Bloom also featured. I remember watching the movie in college, highly entertained by the humorous portrayal of Jack Sparrow as a rather bumbling, yet still effective, pirate. For those who have been to Disneyland, you may even recognize the prison scene from the movie as a replica of part of the Pirates of the Caribbean ride.

Naturally, with the success of the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, Disney has been hit with a couple of lawsuits with various authors and artists claiming that the film infringed their copyrights. In the most recent case, a producer and two writers claimed that they had submitted a script with concept art to Disney back in 2000, but that Disney elected not to purchase the script. Disney later released Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl in 2003, followed by four additional movies in the franchise in subsequent years. The plaintiffs alleged that the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise infringed their original script, based on character, setting, theme, dialogue, and other elements.

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Last week, the District Court for the Central District of California dismissed the case on a motion for summary judgment, finding that the script submitted to Disney in 2000 and the script of Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl were not substantially similar. The judge ruled that the only similarities that could be found were those common to pirate stories, or generic character concepts that are not afforded copyright law. This concept is fundamental to copyright law: you can’t copyright an idea. I repeat. You. Can’t. Copyright. An. Idea. While an author may hold copyright protection in the particular expression of his idea, stock characters and general plotlines and the like are not eligible for copyright. The idea/expression dichotomy is critical to a functioning copyright system, otherwise ideas would be locked away and the public would be deprived of the differing forms of expressing that same idea. After all, there’s nothing new under the sun. (For the Nick Saban/Lebron James variation of this topic, see here.)

The plaintiffs in the case claimed that both their script and Pirates of the Caribbean portrayed pirates in a different light (as humorous and jovial, rather than scary) and that both works involved cursed pirates. The judge dismissed these claims, finding that an idea like cursed pirates is a basic plot premise. Again, this is simply an idea and not any specific expression of the idea.

The plaintiffs also asserted that Jack Sparrow infringed on their screenplay’s character of Davey Jones. The complaint claims that Jack Sparrow’s portrayal as “funny, not feared,” referenced as a “good man,” and “cocky but with a ‘heart of gold’ and a drunk who loves rum” is substantially similar to the script’s Davey Jones who is “a dashing young rogue, ‘clean-shaven, hair pinned back in a tail’” who is also “cocky, brave and a drunk.” The court dismisses the claims of substantial similarity, finding that “cockiness, bravery, and drunkenness are generic, non-distinct characteristics which are not protectable.” The remaining elements are simply not substantially similar, with Jack Sparrow’s appearance anything but clean-shaven. Ultimately, the claimed similarities are merely stock character elements and, even in combination, are insufficient for copyright protection.

Turning to theme, the plaintiffs allege that because both the script and the films involve mutiny and betrayal, substantial similarity exists. The court quickly dismisses this argument, noting:

Sponsored

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Mutiny and betrayal . . . are generic stock themes and flow naturally from the premise of pirates and ships, and therefore unprotectable. Moreover, while Plaintiffs’ Screenplay portrays Davey Jones as Jack Nefarious’s first mate, Davey Jones does not lead a mutiny against Nefarious. In contrast, in Defendants’ Films, Captain Barbossa was Jack Sparrow’s first mate, but led a mutiny to overtake Jack’s ship and marooned Jack on an island. Accordingly, the idea of ‘betrayal’ in the parties’ works is not depicted in a substantially similar manner.

The plaintiffs then allege that the setting of the two works are substantially similar because they both take place on ships in the Caribbean and in caverns. The court points out, however, that these settings are not copyrightable expression “because they flow from the natural premise of a story based on Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean theme park ride.” That’s right, the plaintiffs themselves were inspired by preexisting works, namely the Disneyworld ride which involves skeleton pirates in a cavern in the Caribbean. Because again, there’s nothing new under the sun, and inspiration is drawn from existing culture. The plaintiffs even acknowledged that historically, a majority of pirate stories take place in the Caribbean.

Finally, the court also dismisses the plaintiffs’ claims that the dialogue in the film infringes the script:

While the Court notes a few instances of similar dialogue based on its objective review of the works, such dialogue appears in different contexts, are made by different characters, and/or are unoriginal because they are identical or substantially similar to portions of the theme song from Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean theme park ride.

An idea can’t be copyrighted and for very good reason. If the claimed elements of similarity on theme, setting, and stock character elements were enough for copyright protection, creation of new cultural works would be seriously diminished. The idea/expression distinction is a critical copyright concept that promotes the creation of new expression, including inspiration from existing sources.

Sponsored

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Krista L. Cox is a policy attorney who has spent her career working for non-profit organizations and associations. She has expertise in copyright, patent, and intellectual property enforcement law, as well as international trade. She currently works for a non-profit member association advocating for balanced copyright. You can reach her at kristay@gmail.com.