Prison Guards -- Overworked And Underpaid. No Wonder Epstein Died.

Two weeks after Jeffrey Epstein’s apparent suicide death while awaiting trial in the Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC) in downtown Manhattan, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has transferred the MCC prison warden elsewhere and put the two prison guards on duty during the time of Epstein’s death on indefinite leave.

Two weeks after Jeffrey Epstein’s apparent suicide death while awaiting trial in the Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC) in downtown Manhattan, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has transferred the MCC prison warden elsewhere and put the two prison guards on duty during the time of Epstein’s death on indefinite leave.

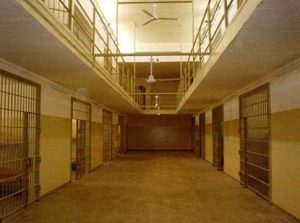

These are short-term fixes to long-standing problems. There are not enough guards, either in state or federal prisons, to handle the amount of people in jail. This is not a new problem. States have been sounding the alarm about prison-guard shortages for years. Now, with the death of a high-profile inmate like Epstein, perhaps those in charge will push for additional funding and make needed changes. The time is ripe to take a good look at why prison-guard shortages exist and how to address the issue.

The reality of working in any prison is that the job is poorly paid, the conditions crappy and the prestige low.

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

The average hourly starting wage is between $13 and $21 per hour. Depending on whether correction officers (C.O.s) work for city, state or federal institutions, their annual salary might start as low as $36,000, hardly enough to support themselves, forget about a spouse and children.

The hours are long and the conditions sometimes dangerous. The work ambiance is often one of caution at best; paranoia and outright fear at worse. Some inmates are dangerous, and those who want to escape will stop at nothing to do that.

The Houston Chronicle ran these words of advice for people thinking of becoming COs:

Before taking this step, make sure you’re aware of the risks involved. Life as a correctional officer isn’t easy. In fact, it has nothing to do with what you see in movies and TV series. Prison guards have the second highest mortality rates of any profession; extreme stress, substance abuse, depression, workplace injuries and suicidal thoughts, are just a few of their daily struggles.

Sponsored

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

The federal job website for Bureau of Prison (BOP) jobs, USAJobs.gov lists the beginning salary for a federal prison guard at $41,868 and states that there are “many vacancies” nationwide. The perks of the job are described as having a “meaningful career with an agency that truly values a diverse workforce.” But the job deficits list not only the need to use physical force “including deadly force, to maintain control of inmates,” but also “long and irregular hours, unusual shifts, Sundays, holiday and unexpected overtime.”

The “Medical Requirement” section advises that “the duties of these positions involve unusual mental and nervous pressure, and require arduous physical exertion involving prolonged walking and standing, restraining of prisoners in emergencies, and participating in escape hunts.”

Wow. No wonder they don’t get enough applicants.

To be sure, the job does provide good retiree benefits after the CO puts in the required 25 or so years. Many retire in their early 50’s to start new careers, travel or just sit by the beach.

But others are left scarred for life because of what they’ve seen, had to do, or experienced. They have, after all, been working in a prison — one of the most restrictive, cold, impersonal and dangerous places to be. An emotional shutdown can happen, as with any high-stress job working with difficult populations.

Sponsored

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

While many prisoners (in my experience) just want to get through their time without hassle, the few troublemakers can be truly dangerous, emotionally unbalanced, and looking to instigate fights in hopes of bringing lawsuits to make money against the prison for unlawful use of force or physical abuse. Some act violently out of boredom, frustration or just to prove their position in the inmate hierarchy.

As one prison guard put it to me, “We feel like we’re doing time too, but we’re just getting paid for it.”

Working within these conditions could test the patience and emotional balance of even the most stable person. I find in city prisons, where the COs are generally from the same neighborhoods from which the inmates hail, the rapport between guards and detainees is better. Many know each other, understand what they’ve been through, and understand how to quell a potentially explosive situation.

State and federal facilities often hire guards not the same race as the inmates they house. It’s a matter of geography and the racial makeup of prisoners. Most prisoners in the U.S. are black and Hispanic, while many large institutions, far from ethnically diverse urban areas, employ Caucasian workers. At best this can lead to an unfamiliarity between the guards and inmates. At worst, it ratchets up feelings of paranoia and distrust.

What can be done? To attract more prison guards, there have to be enticements starting with higher salaries, and perks like subsidized continued education, merit pay and recreational centers on-site.

On the soft side, institutions should recognize the emotional toll guards face and should provide wellness check-ins, sessions in yoga and meditation and racial sensitivity training to better deal with inmates from different backgrounds.

The U.S. has a crushing number of people in jail, with more inmates per capita than any other country in the world. I’m not advocating for a continuation of this practice; however, if we are going to continue imposing stiff punishments instead of seeking alternatives to incarceration, we then have the concurrent responsibility to make sure prisons have enough COs to guard inmates safely. To do this we need to compensate CO’s fairly and make sure they’re able to deal with the job’s pressures.

The more COs, the less overworked they’ll be. The more they’re paid and appreciated, the more will apply for the job. The better prisoners are treated, the less violence and fewer suicides will occur.

Instead of blaming the two correction officers set to guard Epstein the night of his death, let’s look at what led to this glitch in the system and deal with it.

Toni Messina has tried over 100 cases and has been practicing criminal law and immigration since 1990. You can follow her on Twitter: @tonitamess.