Justice Filtered: Plans To Manage Diversity In The Federal Judiciary

Even with the laudable notion of a more diverse judiciary, aspects of this plan may actually function towards cutting off the nose to spite the face.

Ed. note: Please welcome Dr. Adam Feldman of Empirical SCOTUS to the pages of Above the Law.

Ed. note: Please welcome Dr. Adam Feldman of Empirical SCOTUS to the pages of Above the Law.

Since Donald Trump’s inauguration in 2017, his administration has made major changes to the federal judiciary. This includes filling two Supreme Court seats along with a total of 146 confirmed Article III (federal district, appellate, Supreme Courts, and the court of international trade) judges. Democrats saw their last Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland, fade away without a confirmation hearing. The entire balance of the federal judiciary has been transformed over the past couple of years and for the first time in recent history, Democratic groups are trying to make a campaign issue out of federal court reform. Several groups have come forward with plans to reform or transform the federal judiciary to varying degrees. These plans range from Pete Buttigieg’s court packing plan to attempts to employ different procedures for selecting judges and justices. One consistent critique that follows Democratic nominees though is their lack of consensus on a plan for the courts.

Last week, the group Demand Justice, headed by Brian Fallon and Christopher Kang, laid out a novel plan for judicial reform in an article in The Atlantic. This plan has the goal of bringing diversity to the federal judiciary and limiting nominees to lawyers that have not worked as corporate “Biglaw” partners. To this end, Fallon and co-author Christopher Kang wrote, “If Democrats truly want the next president’s arrival to mark an inflection point when it comes to the composition of the judiciary, we should elevate those whose full-time jobs were on the front lines defending our democracy during this dark period, not those whose paychecks were drawn from corporate clients.”

Generative AI In Legal Work — What’s Fact And What’s Fiction?

They follow this by laying out some bare bones methodology for how this would look in practice: “For starters, there is the question of how to define who counts as a corporate lawyer. We would define it as a lawyer who achieves partner status at a corporate-law firm — such as the large firms known collectively as Biglaw — or who serves as in-house counsel at a large corporation. This would mean lawyers who briefly worked as associates at firms during an early phase in their career would not be excluded.”

While corporate law experience may not be the optimal choice to fill 100 percent of the slots in the federal courts, an effort at increasing diversity is a far cry from total exclusion. UC Irvine’s Professor Rick Hasen provided a thoughtful response explaining some of the problematic aspects he saw with this plan. Concurrently, civil rights attorney Sasha Samberg-Champion opined that this proposal could have been designed as a bargaining chip to start the conversation of judicial reform rather than as a (potentially) binding contract. Democratic nominee Elizabeth Warren came out in favor of the substance of the plan, while not clearly on the side of committing to a no corporate lawyer rule.

Even with the laudable notion of a more diverse judiciary, aspects of this plan may actually function towards cutting off the nose to spite the face. That is to say — while diversity is an unquestionably noble attribute and something sorely needed in the courts, means to get there that include excluding a whole subset of incredibly qualified judicial candidates raise potential problems in their own rights. There are examples of corporate lawyers who became great jurists, just as there are of corporate lawyers who have a penchant to rule in favor of big businesses (a common critique of the Roberts Court from the likes of Senator Sheldon Whitehouse among others).

Leaving the merits of this plan aside for a moment to focus on researching the link between a background as a corporate partner and federal judging, two things are immediately clear. In terms of free resources, even comprehensive sources like the FJC’s Biographical Directory of Article III Judges lacks specific information on judges’ work experience. Take for instance Judge Leslie Abrams who sits on the District Court for the Middle District of Georgia. The FJC’s website lists her law firm experience as “private practice” for the years 2003 through 2010. If we want to learn more, we cannot go to her bio on her court’s website. The court’s website actually doesn’t provide any information about Judge Abrams’s background. Indeed, the most reliable source for this information appears to judges’ senate questionnaires filled out during the nomination process. From this we see that Abrams worked as an associate at Skadden Arps and Kilpatrick Townsend during this period (note that Wikipedia and Ballotpedia have biographical information on many federal judges but it is often in summary form and thus is almost always incomplete).

Sponsored

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Generative AI In Legal Work — What’s Fact And What’s Fiction?

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Actually evaluating the merits of this no corporate lawyer as judges policy involves more than just theorizing. The Atlantic article, for example, states that upon examining current federal appeals court judges, “60 percent were once corporate-law partners.” The implications of this statistic are really in the eye of the beholder. To some this may seem staggering, but to others this might be quite obvious. This statistic shows that the backgrounds of federal judges are not representative of the attorney population across the United States as a whole. But is this consequential? Again, more information may help individual voters determine their positions on this issue for themselves.

It is important to unpack proposals such as that from Demand Justice to understand the ramifications and therefore grasp the costs and benefits of such a plan. Demand Justice’s methodology for determining who fits within the exclusionary category is a bit vague. This methodology, as explained earlier, would simply exclude former Biglaw partners and in-house counsel for large corporations from federal judgeships. One way to begin gauging the merits of such a proposal is through examining what the repercussions would have been had such a plan been in effect at an earlier time. Since this is a proposal for Democratic candidates, we should focus on judges placed on federal courts by a Democratic president.

According to FJC counts, 271 judges were confirmed for their first federal judgeship under President Obama. Obama also nominated several already sitting judges to higher positions (for example, Justice Sotomayor from appeals court judge to Supreme Court Justice), but these elevated judges are not the focus here. One vague point in Demand Justice’s methodology is its description of Biglaw partners. While there is no universal definition for a Biglaw partner, firm size is the major determining factor here. This analysis used 50 lawyers in a firm as a cut point between big and small law. Fifty lawyers in a firm is generally good indicia that a firm has the capacity to handle matters for large corporate clients, although it is by no means the only way to gauge this. Biglaw might mean much larger firms and so the number of judges who previously practiced in such firms might actually be much smaller than those identified herein. Since this notion of a strict cut point for Biglaw is inherently arbitrary though, and because lawyers in a boutique firm might very well handle the same corporate matters as big law attorneys, this at least gives us a place to start the conversation.

Approximately 98 of the 271 new judges, or about 36 percent of the judges identified in this sample, worked as partners at Biglaw firms (those over 50 attorneys in size) at some point prior to their nomination for federal judgeship. These 98 judges are composed of one international trade court judge, 15 courts of appeals judges, and 82 district court judges. While Justice Kagan was an associate at Williams & Connolly, she was never a partner and therefore would not be disqualified under the previously described standards.

The following figure has the positions for all 98 judges who would not be viable nominees if democrats banned nominations of previous Biglaw partners who worked at firms with a minimum of 50 attorneys (click to enlarge).[1]

Sponsored

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

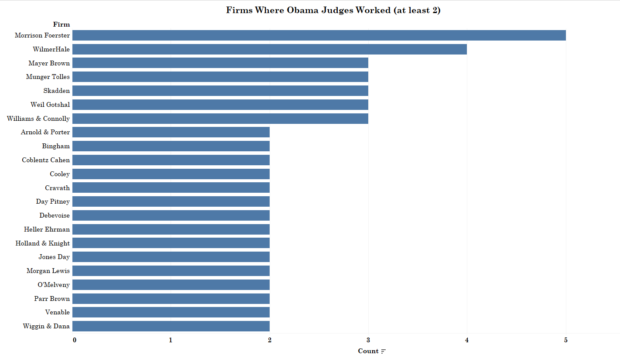

Three Obama nominees were previously partners at Morrison Foerster, three at Mayer Brown, and three at Munger Tolles. Munger Tolles employs approximately 200 attorneys including Obama’s Solicitor General, Donald Verrilli. Morrison Foerster has over 1,000 attorneys worldwide and Mayer Brown has over 1,500.

Not all firms on this list have such a large number of attorneys, though in multiple offices. Lightfoot Franklin, for example, has two offices, in Houston and Birmingham, and around 60 total attorneys. When you look at the matters they handle though, many are for large corporate clients and involve large dollar value actions.

Under Demand Justice’s policy, not all potential judges who worked at these firms would be banned from judicial nominations. Several, like Kagan, worked as associates at these firms but did not continue on to the partner level. To get a sense of the firms where more than one of Obama’s first-time judges worked as either an associate or a partner, the next figure has these aggregate data (click to enlarge).

Five of Obama’s first-time judges worked at Morrison Foerster. Since we know from the previous figure that three were partners, two must have been associates. The other firms on this list are primarily some of the largest and most successful national and international law firms. These 54 attorneys turned judges hailing from prominent firms in one capacity or another underscores the importance presidents place on experience in highly recognized law practices. This is where many lawyers are trained, and where the majority of lawyers, especially those who matriculate from top-tier schools, go after law school.

Law.com regularly details the statistics of law grads that begin their legal work in Biglaw firms. The schools with the highest percent of 2018 grads going on to work in Biglaw firms according to law.com’s statistics were the following (click to enlarge):

Columbia had the highest percentage of grads beginning work at large law firms at 78 percent. The top 10 schools rounded out with Harvard at 58 percent, Georgetown at 56 percent, and University of Chicago at 55 percent of 2018 grads starting their legal careers in Biglaw firms. Suffice it to say that large numbers of lawyers graduating from top schools at least begin their careers in big law.

When we look at Obama’s confirmed judges, many came from the same top-tier schools (click to enlarge).

The vast majority of Obama’s confirmed federal judges came from the top three ranked law schools in the country: Harvard, Yale, and Stanford. Beyond this, in general we see that Obama’s judges mainly hailed from a handful of top-tier law schools, and these law schools were predominately the nation’s top schools, and the schools where the largest percentage of grads went into Biglaw practice. Perhaps one of the deficits in diversity stems from the few law schools that graduate the majority of federal judges.

Below is a table of all judges that would be potentially banned from seeking judgeships according to the Biglaw partner policy, along with their previous employment and the law school they attended.

| Judge | Job | Law School | Court Level |

| Judge Robert Bacharach | Shareholder at Crowe and Dunleavy | Washington University School of Law | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Susan Carney | Counsel at Bredhoff Kaiser | Harvard Law School | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Morgan Christen | Partner at Preston Gates | Golden Gate University School of Law | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Michelle Friedland | Partner at Munger Tolles | Stanford Law School | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Pamela Harris | Partner at O’Melveny | Yale Law School | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Andrew Hurwitz | Osborn Maledon | Yale Law School | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge William Kayatta | Partner Pierce Atwood | Harvard Law School | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Cheryl Krause | Partner at Dechert | Stanford Law School | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Carolyn McHugh | Partner at Parr Brown | University of Utah College of Law | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Patricia Millett | Partner at Akin Gump | Harvard Law School | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge John Owens | Partner at Munger Tolles | Stanford Law School | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Jimmie Reyna | Partner at Williams Mullen | University of New Mexico School of Law | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Srikanth Srinivasan | Partner at O’Melveny | Stanford Law School | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Kara Stoll | Partner at Finnegan Henderson | Georgetown University Law Center | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Paul Watford | Partner at Munger Tolles | University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law | U.S. Court of Appeals |

| Judge Jennifer Groves | Partner at Hughes Hubbard | Columbia Law School | U.S. Court of International Trade |

| Judge Madeline Arleo | Partner at Tompkins, McGuire, Wachenfeld & Barry, LLP | Seton Hall University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Kristine Baker | Partner at Quattlebaum, Grooms, Tull & Burrow | University of Arkansas School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Stanley Bastian | Partner at Jeffers, Danielson, Sonn & Aylward, | University of Washington School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Wendy Beetlestone | Partner at Schnader, Harrison, Segal & Lewis LLP | University of Pennsylvania Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Cathy Bencivengo | Partner at DLA Piper | University of Michigan Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Loretta Biggs | Partner at Davis, Harwell & Biggs and in-house at Coca-Cola | Howard University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Cathy Bissoon | Director at Cohen Grigsby | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Timothy Black | Director at Graydon Head | Northern Kentucky University, Salmon P. Chase College of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Victor Bolden | Counsel at Wiggin and Dana | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Vernon Broderick | Partner at Weil Gotshal | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Debra Brown | Shareholder at Wise Carter Child & Caraway | University of Mississippi School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Nannette Brown | Partner at Chaffe McCall | Tulane University Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Allison Burroughs | Partner at Nutter McClennen | University of Pennsylvania Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Claire Cecchi | Partner at McElroy, Deutsch, Mulvaney & Carpenter | Fordham University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Julianna Childs | Partner at Nexsen Pruet | University of South Carolina School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Theodore Chuang | Counsel at WilmerHale | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Tanya Chutkan | Partner at Boies Schiller | University of Pennsylvania Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Mark Cohen | Partner at Troutman Sanders | Emory University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge William Conley | Partner at Foley Lardner | University of Wisconsin Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Christopher Cooper | Partner at Baker Botts | Stanford Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Daniel Crabtree | Partner at Stinson Morrison | University of Kansas School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Waverly Crenshaw | Partner at Waller Lansden | Vanderbilt University Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Jon DeGuilio | Partner at Barnes and Thornburg | Valparaiso University Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Pedro Delgado Hernández | Partner at O’Neill & Borges | University of Puerto Rico School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge James Donato | Partner at Cooley | Stanford Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Thomas Durkin | Partner at Mayer Brown | DePaul University College of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Sara Ellis | Counsel at Schiff Harden | Loyola University Chicago School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Paul Engelmayer | Partner at WilmerHale | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Katherine Failla | Partner at Morgan Lewis | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Gary Feinerman | Partner at Mayer Brown | Stanford Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Audrey Fleissig | Partner at Peper, Martin, Jensen, Maichel and Hetlage | Washington University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Katherine Forrest | Partner at Cravath | New York University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Haywood Gilliam | Partner at Bingham McCutcheon | Stanford Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Mark Goldsmith | Partner at Honigman Miller | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Madeline Haikala | Partner at Lightfoot Franklin | Tulane University Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge LaShann Hall | Partner at Morrison Foerster | Howard University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Ellen Hollander | Partner at Frank, Bernstein, Conaway & Goldman | Georgetown University Law Center | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Charlene Honeywell | Partner at Hill Ward | University of Florida College of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Mark Hornak | Partner at Buchanan Ingersoll | University of Pittsburgh School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Diane Humetewa | Counsel at Squire Sanders | Arizona State University College of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Amy Jackson | Partner at Venable | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Brian Jackson | Liskow and Lewis | Georgetown University Law Center | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Ketanji Jackson | Counsel at Morrison Foerster | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Richard Jackson | Partner at Holland and Hart | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Abdul Kallon | Partner at Bradley Arant | University of Pennsylvania Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Lucy Koh | Partner at McDermott | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge John Kronstadt | Partner at Arnold & Porter | Yale Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge William Kuntz | Partner at Seward & Kissel | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge John Lee | Partner at Freeborn & Peters | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Matthew Leitman | Partner at Miller Canfield | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge John McConnell | Partner at Motley Rice | Case Western Reserve University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Travis McDonough | Partner at Miller and Martin | Vanderbilt University Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Kevin McNulty | Partner at Gibbons PC | New York University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Amit Mehta | Partner at Zuckerman Spader | University of Virginia School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Laurie Michelson | Partner at Butzel Long | Northwestern University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge James Moody | Partner at Wright, Lindsey, Jennigns | University of Arkansas School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Raymond Moore | Parner at Davis Graham | Yale Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Randolph Moss | Partner at WilmerHale | Yale Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Susan Nelson | Partner at Robins Kaplan | University of Pittsburgh School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge James Oetken | GC at Cablevision Systems | Yale Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge William Orrick | Partner at Coblentz Patch | Boston College Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Gerald Pappert | Partner at Ballard Spahr | Notre Dame Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Linda Parker | Partner at Dickinson Wright | George Washington University Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Jill Parrish | Partner at Parr Brown | Yale Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge James Peterson | Partner at Godfrey Kahn | University of Wisconsin Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Edgardo Ramos | Partner at Day Pitney | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Yvonne Rogers | Partner at Cooley | University of Texas School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Robin Rosenberg | Partner at Holland & Knight | Duke University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Lorna Schofield | Partner at Debevoise | New York University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Richard Seeborg | Partner at Morrison Foerster | Columbia Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Michael Shea | Partner at Day Pitney | Yale Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Robert Shelby | Partner at Snow Christensen | University of Virginia School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Michael Simon | Partner at Perkins Coie | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Josephine Staton | Partner at Morrison Foerster | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Leonard Strand | Partner at Simmons Perrine | University of Iowa College of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Indira Talwani | Partner at Altshuler Berzon | University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge John Tharp | Partner at Mayer Brown | Northwestern University School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Jon Tigar | Partner at Keker & Van Nest | University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Michael Urbanski | Partner at Woods Rogers | University of Virginia School of Law | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Derrick Watson | Partner at Farella Braun + Martel | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Robert Wilkins | Partner at Venable | Harvard Law School | U.S. District Court |

| Judge Gregory Woods | Partner at Debevoise | Yale Law School | U.S. District Court |

Many of the judges who would not be disqualified under this Biglaw partner rule worked in private practices as solo practitioners or with a limited number of partners. This does not necessarily mean they represented different clients than other judicial nominees, but with smaller firms they likely had fewer resources to manage multiple large accounts. Thus, firm size might be a good proxy for the extent of this type of business a firm or attorney can handle.

In the end, this is a question of what matters in judging. Even if we take the importance of diversity on the federal bench as a given, the means to seek this are still unclear. The bottom line is that voters need to ask themselves what needs to be reformed. We have clusters of judges coming from a top law schools, going into big firm jobs, and we see some continue in these jobs while others go into public interest work, academia, or other non-Biglaw jobs. Many of Obama’s picks for federal judges worked in the Biglaw world and a large minority went on to become partner in such firms. This may affect the the way they decide cases, but other factors such as political preferences have been shown to explain a large percentage of voting behavior as well. Further statistical research into this subject may illuminate whether the relationship between practicing as a Biglaw partner and supporting corporate interests in judging is truly robust. Without this research, such inferences remain at least somewhat speculative.

Ultimately, voters need to decide what the most important factors are in choosing future federal judges just as politicians must decide on certain criteria that will determine the pool of potential judges they choose from. This may be related to judges’ previous work experiences although this equally may be related to other factors that influence judges’ decisions. More studies and greater resources may help us understand the correlates between judges’ backgrounds and votes for corporate causes. At this point though, even if the public’s goal is to minimize judges’ votes for corporate causes, the direct link between practicing as a corporate partner and such votes is unclear, and evidence is sparse that practicing as a corporate partner is the most decisive attribute leading to such voting practices.

[1] Note that the firms collected here are determined by size and not by practice specialization. It is entirely possible that some firms would not fit the corporate law model described by Demand Justice. Additional information on exactly what constitutes a corporate firm would help further clarify which firms might not fit into this category.

Dr. Adam Feldman is an attorney with a J.D. from U.C. Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law. He also has a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Southern California. Dr. Feldman previously practiced as a trial lawyer in large and boutique firm settings in the Los Angeles area. He has expertise in statistical analysis and data modeling and has published a variety of articles in peer and law reviewed journals and book chapters in these areas. Dr. Feldman currently teaches political science and law courses and consults on legal strategy for law firms and interest groups.