Being A Prisoner During COVID-19

Calls received from jail are panicked. One client at Rikers said, 'Things are so bad in here, I think a riot is going to break out.'

There are two types of prisoners — the ones who’ve been convicted of crimes and the ones who haven’t and are merely in jail because they can’t afford bail to get out while they await trial.

There are two types of prisoners — the ones who’ve been convicted of crimes and the ones who haven’t and are merely in jail because they can’t afford bail to get out while they await trial.

Both sets of prisoners are affected by quarantines caused by the coronavirus. But for those who haven’t yet been found guilty and want their cases to move along as quickly as possible, tensions are running high.

Their court cases have now been postponed a minimum of two months. Jury trials in New York and at least 20 other states have been suspended. Cases are being rescheduled without the defendant or his lawyer in court. Inmates awaiting trial are feeling angry, frustrated, and uncertain. Who’s watching out for them?

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Lawyers are no longer allowed to visit their clients in any federal prison and many state jails. Families and friends cannot visit. Inside, rumors abound.

Many fear the prison workforce, at least in New York State, will be cut by 50 percent pursuant to the governor’s mandate that half of state workers stay home.

Calls I get from jail are panicked. If there’s a staff shortage, inmates fear their phone calls –- the one lifeline they have with the outside world –- will be suspended or significantly curtailed. They’re worried about how their families are doing. Whether anyone’s sick or lost a job.

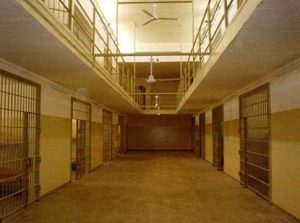

They’re worried for their own health. Some fear the guards they come in contact with are not properly screened and may be virus carriers. Because many inmates sleep in “dorms” -– giant rooms with rows of 20 beds just a foot and half apart, they cannot socially distance themselves. If the guy in the next bed coughs, he won’t be wearing a face mask.

Sponsored

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

One client at Rikers told me, “Things are so bad in here, I think a riot is going to break out.”

I reassured him that of all populations, prisoners might be the best protected. Most are healthy young men who work out every day, remain isolated from the general population and follow a routine in a controlled environment. It didn’t do a lot to soothe him.

He wanted to know when his case would go to trial. I told him that I didn’t know.

Of the thousands of inmates convicted and now serving time in state or federal prisons, many are older guys finishing off long sentences and thus most susceptible to the worst consequences of the virus. If sick, they fear the treatment they’ll receive will be inadequate.

As for New York City, which normally processes thousands of criminal cases a day, no defendants will be brought to court from jail unless absolutely necessary. Cases involving people out of jail are being adjourned to mid-June or later. Only a few court parts are functioning, and no one but “essential” personal is being granted court entry.

Sponsored

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

Thankfully, I’m not “essential.” I stay home, take walks, answer my clients’ questions as best I can and try to focus on ongoing work like motions, discovery, and legal research. But I worry about my clients.

I urge them all to stay calm and focused. Instead of becoming an agitator, maybe one of them could become a leader who keeps things copacetic in jail. This would help him down the road in plea negotiations.

The time they spend now in jail (although it must feel like limbo) will be credited to them if, ultimately, they’re convicted. But if they’re hoping for their case to be tried speedily or for the prosecutor’s office to be held to its burden of going to trial within a set statutory period post-arrest, that’s all been waived by government decree.

For those hoping to eventually be acquitted –- hang in there. You’ll see a jury someday. It’s just going to take a little longer.

Toni Messina has tried over 100 cases and has been practicing criminal law and immigration since 1990. You can follow her on Twitter: @tonitamess.