Originalist Sinners And Saints

Which judges are using originalist interpretation?

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Ed note: This article first appeared on The Juris Lab, a forum where “data analytics meets the law.”

In a lecture given in 2010, then-Supreme Court Justice Scalia articulated, “My burden is not to show that originalism is perfect, but that it beats the other alternatives, and that, believe me, is not difficult.” Scalia was one of the most fervent proponents of the use of originalism, the view that writings and predominately the Constitution should be understood based on the time they were written, in interpreting judicial texts. In recent years, his legacy can be found in the large body of judges that look to and use originalist premises in their decisions. This post looks at who, where, and how originalism has been expounded in recent decisions from courts around the nation.

The data for this post is based on all opinions in the last six months (since October 2020) that used the word “originalism” or used “original” within two words of “meaning” in an opinion. A handful of decisions were removed from the dataset because they were clearly irrelevant (for example the search results returned the sentence from Vogel v. McCarthy Burgess & Wolff, Inc. (NDIL), “Based on the Court’s review of the record, it appeared that the parties did not include the original invoice — meaning the invoice that Payless sent to Vogel, before MB&W got involved — in their summary judgment filings.”) I use the phrasing of originalism loosely at the outset of this post to look both at constitutional interpretation and statutory interpretation using originalist principles, and then look specifically at the judges that recently used originalist principles solely for constitutional interpretation.

First a look at the differing use of originalist principles by state and federal judges.

While it is evident that federal judges focus on the Federal Constitution and provisions from the Bill of Rights, state judges look mainly to state constitutions and statutes. Originalist interpretation of the U.S. Constitution are less prevalent in state courts as might be expected based on principles of federalism and from the difference in the general nature of cases before federal and state court judges.

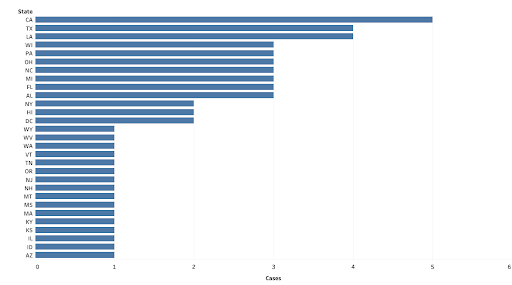

Using the same broad view of originalism, we can also inspect the frequency with which originalist interpretation has been espoused within individual states by both federal and state court judges.

Judges in the most populated state and part of the Ninth Circuit, California, resorted to originalism in the most opinions, five, followed by judges two states in the Fifth Circuit, Texas and Louisiana, with four opinions each. Many more states had at least three opinions that related to originalism.

Focusing on originalist interpretations of only the federal and state constitutions, the next graph shows all the judges that engaged with originalist principles in at least one opinion during this period.

The only judge to rely on originalist interpretation (based on the search terms in the post) in four opinions during this period was Trump appointee Judge Oldham from the Fifth Circuit. An example of Judge Oldham’s use of originalism comes in United States v. Beaudion where he wrote, “Beaudion argues that Heckard violated the Fourth Amendment by obtaining Davis’s GPS coordinates via a defective warrant. We therefore begin with the original public meaning of the Amendment. See, e.g., Atwater v. City of Lago Vista, 532 U.S. 318, 326, 338–39, 121 S.Ct. 1536, 149 L.Ed.2d 549 (2001).”

Two judges relied on originalism in three opinions. The first was another Trump appointee, Supreme Court Justice Gorsuch who in some sense picked up the job of championing originalism on the Court following Justice Scalia’s passing. An example of Justice Gorsuch’s usage comes in his concurrence in Ford Motor Company v. Montana Eighth Judicial District Court where he wrote, “None of this is to cast doubt on the outcome of these cases. The parties have not pointed to anything in the Constitution’s original meaning or its history that might allow Ford to evade answering the plaintiffs’ claims in Montana or Minnesota courts.”

The other judge that relied on originalist interpretation three times was Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Bradley. An example of her use comes from her dissent in State v. Roundtree where she wrote, “Applying the original public meaning of this bulwark of liberty, the United States Supreme Court more than a decade ago finally dispelled the prevalent, but historically ignorant notion that the Second Amendment protects merely a collective, militia member’s right.”

Originalism is often seen as a conservative doctrine, but it has been used more frequently by liberals in recent years which is evident from the Democratic appointees present on the graph above including Justice Kagan from the U.S. Supreme Court. Nonetheless, as the following graph shows, this is still a doctrine mainly relied on by Republican appointees to various courts.

Use by Republican appointees almost triples that by Democratic appointees. Even if Scalia helped make this doctrine more palatable among liberals than it had been in past, it is will be a long road and will be an uphill battle before Democratic appointees begin to approximate reliance on originalist principles of constitutional interpretation in the same manner as it is used by Republican appointees.

Data from the post is available here.

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. For more information write Adam at afeldman@thejurislab.com.

Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.