A Closer Look At The 2021 Am Law 200 Rankings

The biggest Biglaw behemoths did well in 2020, but what about the firms one tier down?

(image via Getty Images)

Ed. note: A version of this column originally appeared on Original Jurisdiction, the latest Substack publication from David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction on its About page, and you can subscribe through this signup page.

By now we all know the story of how the Am Law 100 fared in 2020. Contrary to what many of us predicted, the Am Law 100, the nation’s 100 largest law firms by revenue, hit new highs in terms of gross revenue, revenue per lawyer, and profits per equity partner. For Biglaw, last year was a very, very good year.

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

But how about the firms that the American Lawyer refers to as the “Second Hundred,” the firms ranked #101 to #200 in terms of total revenue? Taken as a whole, these firms are not just smaller in revenue than the Am Law 100, but they also tend to be smaller in headcount, less profitable, and less prestigious.[1] Was 2020 as kind to them as it was to their higher-ranked peers?

The American Lawyer just published its Am Law 200 rankings and accompanying report, and the big-picture answer is that the Second Hundred firms did … fine. They didn’t kill it like the Am Law 100 firms, but they also fared reasonably well, considering the global pandemic and economic downturn that loomed over last year. They did better than many of their clients, and they did better than many of us (and them) expected when the pandemic hit, when numerous firms started instituting austerity measures left and right. Here’s how the Second Hundred performed as a group:

- Total revenue: $20.8 billion, up 1.1 percent.

- Average revenue per lawyer (RPL): $707,506, up 3 percent.

- Profits per equity partner (PPEP): $863,449, up 8.8 percent.

These numbers, standing alone, seem entirely respectable — but they’re positively mediocre compared to the numbers for the Am Law 100:

Sponsored

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

- Total revenue: $111 billion, up by 6.6 percent.

- Average revenue per lawyer (RPL): $1.05 million, up by 5 percent.

- Profits per equity partner (PPEP): $2.23 million, up by 13.4 percent.

I was surprised at the magnitude of the difference between the Am Law 100 and Second Hundred firms. The total revenue of the Am Law 100 is more than five times the total revenue of the Second Hundred. Average revenue per lawyer at an Am Law 100 firm is almost 50 percent higher than RPL at a Second Hundred firm. And profits per equity partner at an Am Law 100 firm are 2.5 times the PPEP at a Second Hundred firm.

The already large gap between Am Law 100 and Second Hundred firms only increased last year, since Am Law 100 firms grew these three key metrics at a much faster rate than their peers in the Second Hundred. These differences are why Brad Hildebrandt, founder of the legal management consultancy Hildebrandt Inc., said that comparing the Am Law 100 to the Second Hundred is the proverbial apples-to-oranges comparison.

Why did the Am Law 100 outperform the Second Hundred by such a large margin during the pandemic? The always insightful Dan Packel identifies several factors, including more resources and better technology, which allowed the Am Law 100 to transition to remote working more quickly and efficiently; greater diversity in terms of practice areas, industries, and geographies, which insulated the Am Law 100 from the serious blows dealt to specific sectors during the downturn; and a stronger client base in general.

But one interesting thing that can make it tougher to generalize about the Second Hundred is that they’re a much more diverse group than the Am Law 100:

Sponsored

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

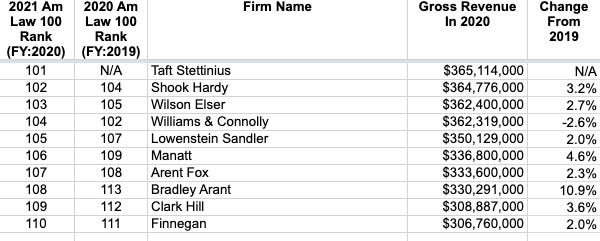

A Midwest powerhouse in its first year after a blockbuster merger [Taft Stettinius]. A single-office elite litigation boutique [Williams & Connolly]. A sprawling insurance defense legacy firm that’s expanded into transactional work and beyond [Wilson Elser]. An IP specialty shop [Finnegan]. And a firm that’s placed a bet on multidisciplinary practice, with a growing number of consultants working alongside lawyers [Manatt]. This sampling of five entirely different business models found within just the first ten spots in the Second Hundred is a microcosm of the diversity of the group.

Here are the first 10 firms in the Second Hundred, i.e., the firms ranked #101 to #110 in gross revenue. For the full list, check out the American Lawyer.

The #1 firm in this group, Taft,[2] is very different from, say, the #4 firm, Williams & Connolly. Taft is a full-service firm with almost 600 lawyers across a dozen offices, mostly in the Midwest; W&C is an elite litigation shop with around 300 lawyers in a single D.C. office. The equity partnership of Taft, at 349 lawyers, is larger than all of Williams & Connolly, at 336 lawyers. And W&C is far more profitable than Taft, with PPEP of $1.448 million, compared to Taft’s $745,000. These two firms, both in the top 10 of the Second Hundred, have far less in common than pretty much any two members of the top 10 firms in the Am Law 100.

Aside from Taft shooting to the top, thanks to its merger with Minneapolis-based Briggs and Morgan, there wasn’t much movement in the top 10. Elsewhere in the rankings, four other firms joined the Am Law 200, in addition to Taft: Waller Lansden, Offit Kurman, FisherBroyles, and Herrick Feinstein. The most notable is FisherBroyles, the first “virtual” or “distributed” law firm to join the Am Law 200 — and surely not the last, given the continued growth of these firms, which should only accelerate now that the pandemic has taught us that working remotely can work quite well.

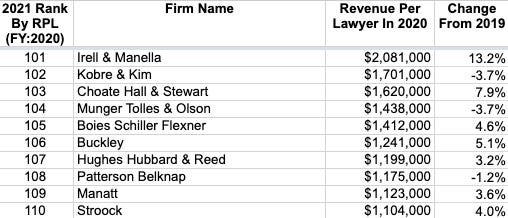

One firm fell from the Am Law 100 into the Am Law 200: Boies Schiller, which dropped from #93 to #130. This wasn’t a shock, since the Am Law 200 rankings are based on revenue, and BSF lost a lot of revenue when it lost a lot of equity partners last year. But it’s interesting to note that Boies actually grew its revenue per lawyer during 2020 by a respectable 4.6 percent, to $1.412 million, and PPEP, while down significantly, was still $2.3 million. As for 2021 performance, BSF came into this year with something to look forward to: fees from its work on the $2.7 billion settlement in the Blue Cross Blue Shield antitrust litigation.

Speaking of revenue per lawyer, widely regarded as the most reliable indicator of a firm’s financial performance, let’s look at the top 10 firms among the Second Hundred for RPL. Again, for the full list, see Am Law.

Lots of prestigious litigation powerhouses here, including Irell, Kobre & Kim, Munger Tolles, Boies Schiller, and Patterson Belknap. But the litigation focus might also explain why the Second Hundred didn’t do as well as the Am Law 100 overall. Transactional practice enjoyed a much better year in 2020 than litigation, which suffered from extended courthouse closures and the cancellation or postponement of lucrative trials — so to the extent that the Am Law 100 firms are more focused on transactional work than the Second Hundred, they had a better year last year. Cf. Mammas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Litigators.

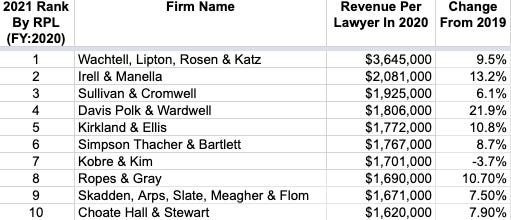

Interestingly enough, as the American Lawyer points out, some of the revenue per lawyer figures for Second Hundred firms are higher than the RPL figures at many Am Law 100 firms. The RPL figures of Irell, Kobre & Kim, and Choate would put them in the top 10 in a combined ranking of the Am Law 100 and Second Hundred firms by revenue per lawyer:

In fact, Irell’s RPL of almost $2.1 million puts it ahead of Sullivan & Cromwell, Davis Polk, Kirkland & Ellis — every firm in the Am Law 200 except for Wachtell.

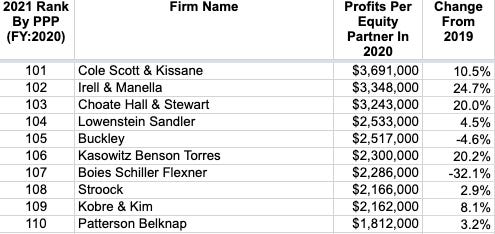

Finally, let’s take a look at the 10 firms in the Second Hundred with the highest profits per equity partner:

If you’re not familiar with Cole Scott, it’s a 541-lawyer firm with 13 offices across the state of Florida. The firm is best known for insurance defense litigation.

Wait, hold on — insurance defense litigation? How on God’s green earth does a firm focused on insurance defense work, a practice area with notoriously low billing rates and profit margins, boast PPEP of almost $3.7 million? Here’s how: Cole Scott has 541 lawyers, and just three equity partners.[3]

The other firms on the list are familiar names. Irell is a perennially profitable firm, and despite some notable partner departures in the past few years, it looks like its strategy of focusing on high-end IP and commercial litigation is paying off. It grew its PPEP by almost 25 percent in 2020 — and 2021 might be even better, considering that in March the firm won a $2.2 billion patent award on behalf of its client, VLSI Technology LLC, against Intel.

Choate did well, which wasn’t unexpected, considering the firm’s strength in transactional work as well as litigation. More surprising is the strong performance of Kasowitz Benson. Industry observers have wondered for a while about the fate of the litigation-focused firm after Marc Kasowitz is no longer around, and the departure of seven partners in February to launch a new boutique, Glenn Agre Bergman & Fuentes, surely didn’t help in terms of succession planning (or lack thereof).

But based on that nice 20-percent increase in PPEP, things at Kasowitz are just fine — for now. Kasowitz isn’t the most transparent of firms — partners other than Marc Kasowitz have shockingly little information about the firm financials — but when the firm is doing well, Marc can pay his people enough to keep them happy.

The PPEP numbers for the top 10 firms in the Second Hundred look nice, standing alone — but again, they pale in comparison to the PPEP figures for Am Law 100 firms. Cole Scott’s $3.7 million would land it in 17th place in PPEP if it were an Am Law 100 firm, one spot behind Paul Hastings and one spot ahead of Cleary Gottlieb.

So that’s PPEP. Let’s now talk about PPP — no, not the old moniker for PPEP (formerly known as “Profits Per Partner”), but the federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program. Per the American Lawyer, 44 of the Second Hundred firms took out forgivable Paycheck Protection Program loans from the federal government, compared with zero firms in the Am Law 100 (many of which were ineligible as businesses with more than 500 employees). As Dan Packel explains, cash from these loans wasn’t included in firm revenue under Am Law’s methodology, but it could get reflected in net income figures if money was ultimately directed to partner comp.

In closing, what can be said about the Am Law 100 and Second Hundred firms, now that all of last year’s financial figures are in? In 2020, the super-rich got richer — and the sorta-rich did just fine too.

[1] The key language here is “taken as a whole”: the Second Hundred firms, collectively, are less profitable and prestigious than the Am Law 100 firms, collectively. But certain individual firms in the Second Hundred, such as Williams & Connolly, Munger Tolles, and Irell & Manella, are more profitable and prestigious than many Am Law 100 firms.

[2] Taft, which you can think of as the Cravath of Cincinnati, has an interesting history. It’s quite old, tracing its roots back to 1885, and yes, there is a connection to former president and chief justice William Howard Taft. Two of President Taft’s sons, Robert A. Taft and Charles P. Taft II, co-founded one of the predecessor firms to today’s Taft.

[3] It’s actually amazing that Cole Scott doesn’t have PPEP higher than $3.7 million, considering that its leverage — the ratio of all lawyers who aren’t equity partners to equity partners — is a staggering 179.33. But the average revenue per lawyer at Cole Scott is a mere $315,000, and the average profit per lawyer is around $20,000. Compare that to the revenue per lawyer at Wachtell Lipton, $3.645 million — meaning that a single Wachtell lawyer generates more revenue than 11 lawyers at Cole Scott.

David Lat, the founding editor of Above the Law, is a writer and speaker about law and legal affairs. You can read his latest writing about law and the legal profession by subscribing to Original Jurisdiction, his Substack newsletter. David’s book, Supreme Ambitions: A Novel (2014), was described by the New York Times as “the most buzzed-about novel of the year” among legal elites. Before entering the media and recruiting worlds, David worked as a federal prosecutor, a litigation associate at Wachtell Lipton, and a law clerk to Judge Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. You can connect with David on Twitter (@DavidLat), LinkedIn, and Facebook, and you can reach him by email at davidlat@substack.com.

David Lat, the founding editor of Above the Law, is a writer and speaker about law and legal affairs. You can read his latest writing about law and the legal profession by subscribing to Original Jurisdiction, his Substack newsletter. David’s book, Supreme Ambitions: A Novel (2014), was described by the New York Times as “the most buzzed-about novel of the year” among legal elites. Before entering the media and recruiting worlds, David worked as a federal prosecutor, a litigation associate at Wachtell Lipton, and a law clerk to Judge Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. You can connect with David on Twitter (@DavidLat), LinkedIn, and Facebook, and you can reach him by email at davidlat@substack.com.